Following the first publication of the complete works of Han Youngsoo in Seoul Modern Times last year, the resulting encouragement and interest exceeded my expectations. While a positive response was expected from my friends, the book also received great interest from the media. International recognition followed, as we were invited to show at the renowned photography festival ‘Recontres d’Arles’ in France. New fans of Han’s work were discovered across the world, which came as a continual surprise.

지난 해 한영수 전집의 첫 결과물인 [서울모던타임즈, Seoul Modern Times]를 출간한 이후, 예상했던 것보다 훨씬 많은 격려와 큰 관심을 받았다. 가까운 지인들의 호응은 물론이었고, 많은 신문과 잡지에서도 관심을 보여주었다. 그리고 세계적인 사진축제인 프랑스 아를사진축제(Rencontres d’Arles)의 전시에 참가하게 되어 국제적인 관심까지 동시에 받게 되었다. 이러한 과정에서 다양한 국적의 여러 팬들도 생기게 되었는데 그 과정은 놀라움의 연속이었다.

이렇게 많은 분들의 적극적인 격려와 도움이 큰 용기가 되어 두 번째 사진집을 준비하게 되었다. 사진작가 한영수의 사진집을 시리즈로 출간한다는 계획은 남겨진 필름과 밀착인화물을 처음 접한 이래 계속 생각해온 것이지만, 막상 두 번째 사진집의 주제를 정하는 데에는 많은 고민을 할 수 밖에 없었다. 그리고 결정한 것이 바로 ‘어린이’ 사진이다.

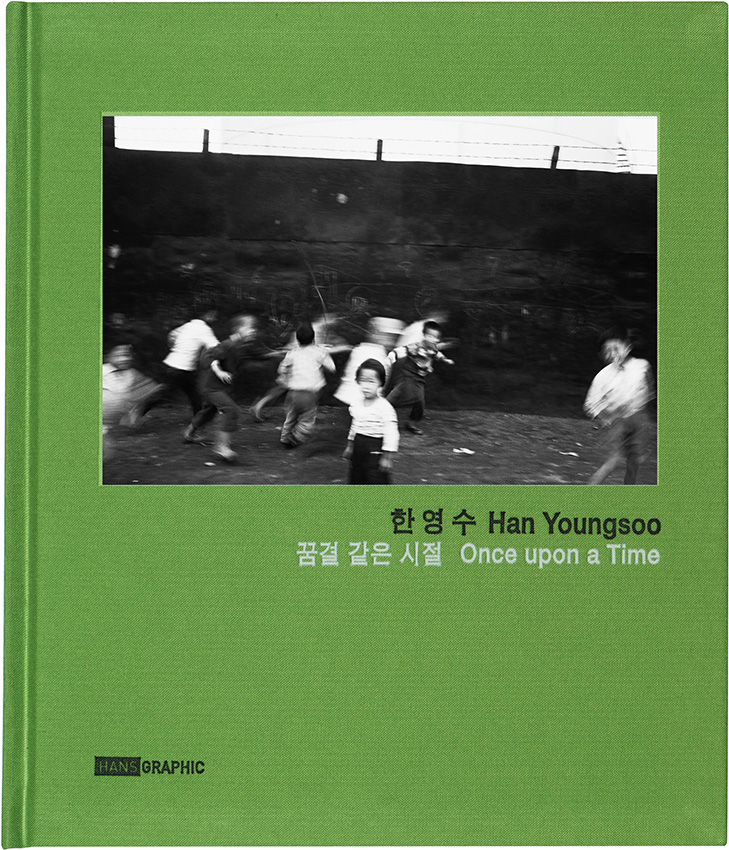

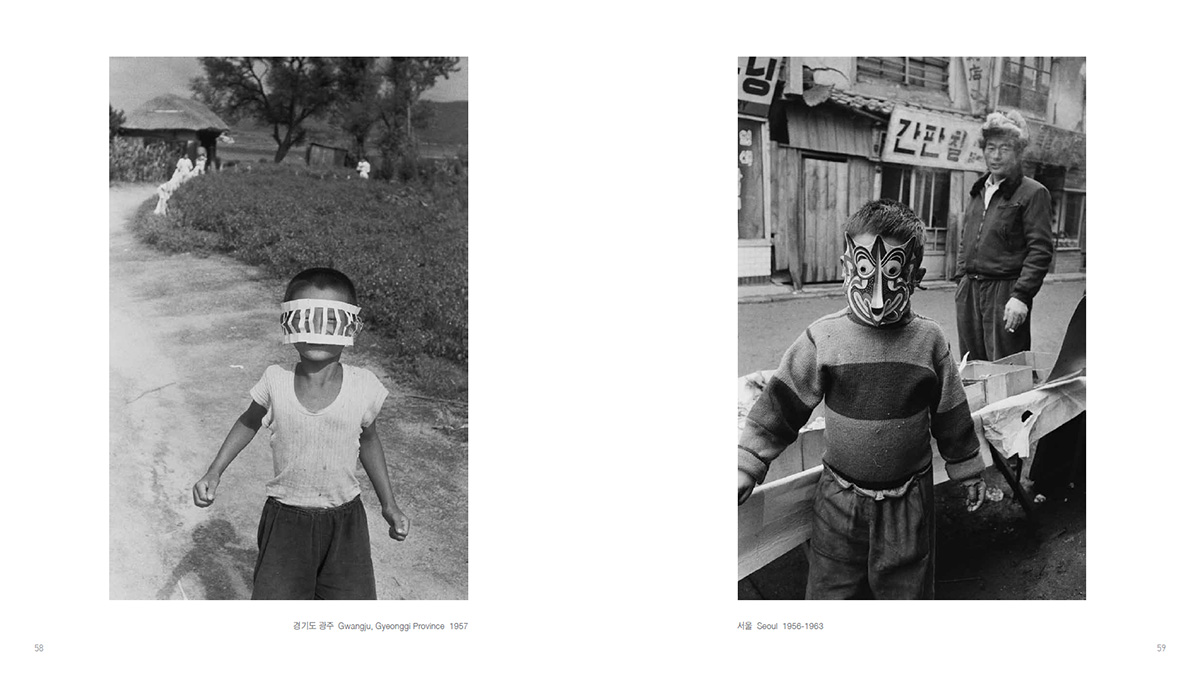

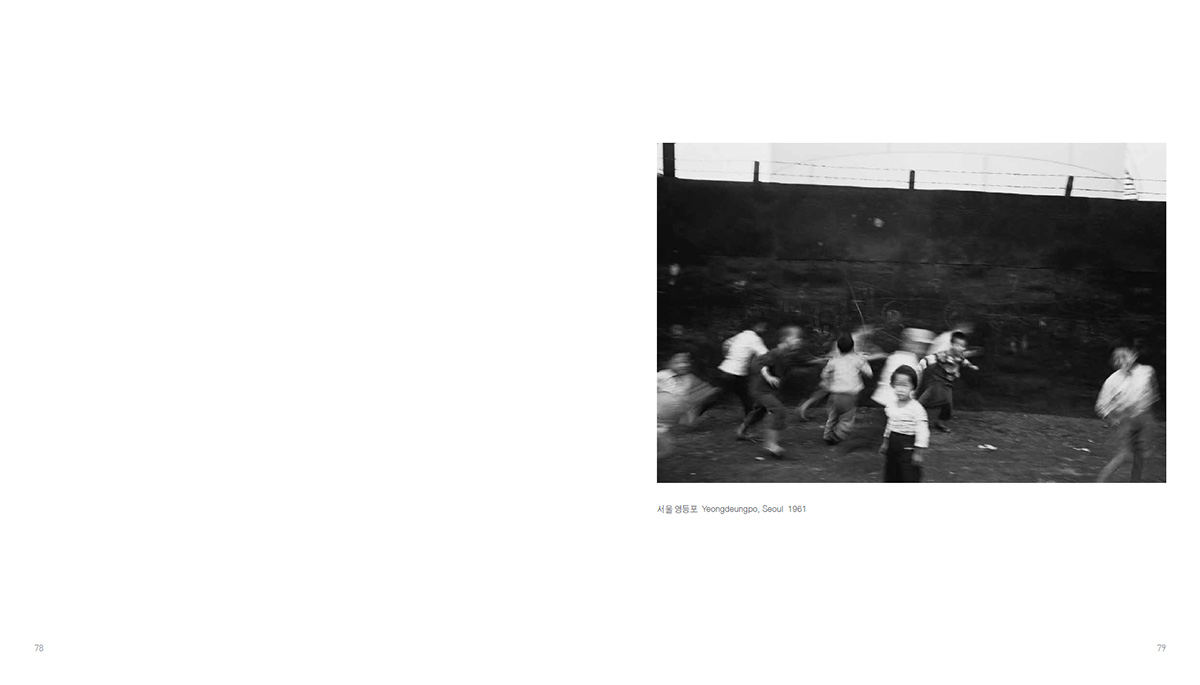

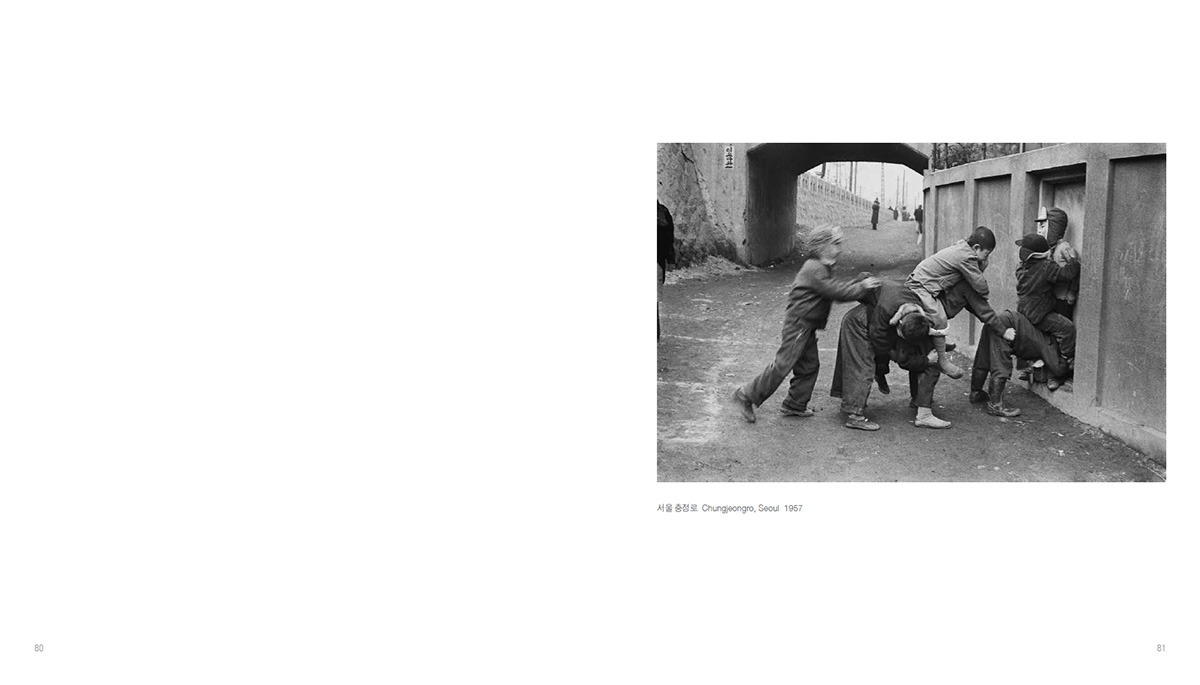

사진집 [꿈결 같은 시절, Once Upon a Time]은 1950-60년대 어린이들의 모습을 담고 있다. 이때는 전쟁 후의 힘들고 어렵던 시절이면서 동시에 아픔을 딛고 재건이 시작되던 시기였다. 그런 시대적 배경 속에서도 사진 속 아이들은 하나같이 순수하고 긍정적인 모습이다. 이것은 사진가 한영수가 아이들을 통해 미래를 보는 시선이다. 이 사진들에 실려 있는 것은 아마도 지금 막 노년에 접어든, 재건의 시대를 거쳐 지금의 대한민국을 만든 바로 그 세대들의 어린 시절일 것이다.

이번 사진집에는 사진을 촬영한 장소와 시간을 추가하였다. 이 작업은 작가가 생전에 출간한 사진집에 실린 사진설명과 작가가 직접적은 필름 정리화일 귀퉁이의 조각 메모들을 마치 퍼즐의 조각처럼 맞춰나가면서 시작되었다. 이러한 작업은 마치 작가의 발걸음을 따라가는 것과 같다. 비록 아직은 완전하지 않지만, 이 퍼즐 맞추기는 한영수 전집 시리즈가 끝날 때까지 계속될 것이다.

이 사진집을 출간하면서 많은 분들의 응원과 도움을 받았다. 가장 먼저 아를사진축제에 한영수의 작품이 전시될 수 있도록 도와주신 구본창 선생님께 감사 드린다. 그리고 한영수의 사진 작품에 많은 애정을 보여주셨으며 사진 촬영 장소를 찾아내는 데 도움을 주신 최종현 선생님께 감사 드린다. 또한 느닷없는 부탁에도 흔쾌히 소중한 글을 써주신 이문웅 선생님께 감사 드린다. 선생님의 글은 사진작가 한영수의 작품이 가지고 있는 또 다른 가치를 되새겨볼 수 있는 기회가 되었다. 그리고 무엇보다도 그동안 한영수의 작품을 사랑해 주시고 사진집의 발간을 응원해주신 여러분께 감사의 말씀을 드리며, 한영수문화재단은 앞으로도 출판과 전시 등 다양한 활동을 통해 사진작가 한영수의 작품을 알리기 위해 노력할 것이다.

한 선 정 한영수문화재단 대표

이렇게 많은 분들의 적극적인 격려와 도움이 큰 용기가 되어 두 번째 사진집을 준비하게 되었다. 사진작가 한영수의 사진집을 시리즈로 출간한다는 계획은 남겨진 필름과 밀착인화물을 처음 접한 이래 계속 생각해온 것이지만, 막상 두 번째 사진집의 주제를 정하는 데에는 많은 고민을 할 수 밖에 없었다. 그리고 결정한 것이 바로 ‘어린이’ 사진이다.

사진집 [꿈결 같은 시절, Once Upon a Time]은 1950-60년대 어린이들의 모습을 담고 있다. 이때는 전쟁 후의 힘들고 어렵던 시절이면서 동시에 아픔을 딛고 재건이 시작되던 시기였다. 그런 시대적 배경 속에서도 사진 속 아이들은 하나같이 순수하고 긍정적인 모습이다. 이것은 사진가 한영수가 아이들을 통해 미래를 보는 시선이다. 이 사진들에 실려 있는 것은 아마도 지금 막 노년에 접어든, 재건의 시대를 거쳐 지금의 대한민국을 만든 바로 그 세대들의 어린 시절일 것이다.

이번 사진집에는 사진을 촬영한 장소와 시간을 추가하였다. 이 작업은 작가가 생전에 출간한 사진집에 실린 사진설명과 작가가 직접적은 필름 정리화일 귀퉁이의 조각 메모들을 마치 퍼즐의 조각처럼 맞춰나가면서 시작되었다. 이러한 작업은 마치 작가의 발걸음을 따라가는 것과 같다. 비록 아직은 완전하지 않지만, 이 퍼즐 맞추기는 한영수 전집 시리즈가 끝날 때까지 계속될 것이다.

이 사진집을 출간하면서 많은 분들의 응원과 도움을 받았다. 가장 먼저 아를사진축제에 한영수의 작품이 전시될 수 있도록 도와주신 구본창 선생님께 감사 드린다. 그리고 한영수의 사진 작품에 많은 애정을 보여주셨으며 사진 촬영 장소를 찾아내는 데 도움을 주신 최종현 선생님께 감사 드린다. 또한 느닷없는 부탁에도 흔쾌히 소중한 글을 써주신 이문웅 선생님께 감사 드린다. 선생님의 글은 사진작가 한영수의 작품이 가지고 있는 또 다른 가치를 되새겨볼 수 있는 기회가 되었다. 그리고 무엇보다도 그동안 한영수의 작품을 사랑해 주시고 사진집의 발간을 응원해주신 여러분께 감사의 말씀을 드리며, 한영수문화재단은 앞으로도 출판과 전시 등 다양한 활동을 통해 사진작가 한영수의 작품을 알리기 위해 노력할 것이다.

한 선 정 한영수문화재단 대표

Following the first publication of the complete works of Han Youngsoo in Seoul Modern Times last year, the resulting encouragement and interest exceeded my expectations. While a positive response was expected from my friends, the book also received great interest from the media. International recognition followed, as we were invited to show at the renowned photography festival ‘Recontres d’Arles’ in France. New fans of Han’s work were discovered across the world, which came as a continual surprise.

The positive support and help of these countless people have given me the courage to prepare a second book of series. Although the idea to publish a series of Han’s work has been on my mind since I first encountered his remaining film and contact sheets, I couldn’t help but worry when it came to finally deciding what the subject of the second installment should be. The decision I eventually reached was “children.”

Once Upon a Time comprises photographs of children from the 1950s and 1960s in Korea. It was an era that, while difficult and hard following the destructive years of Korea War, was also a time of overcoming that pain and the beginning of reconstruction. Even against that backdrop of the times, the children captured in these photographs nevertheless remain positive and pure. This manner of looking at the future through youth is the unique result of the photographer’s eyes. The imagery captures the childhoods of today’s older generation, who reconstructed the country from the ground up.

We added the time and location of each photograph in this book. It is a project that began with piecing together the puzzle of Han’s fragmented memos, stuck at angles on files of film, photo captions and descriptions published in catalogues during his lifetime. It is a process that feels like following in his footsteps. And although it is work that has yet to be completed, the puzzle will be pieced together until the last of the series is finished.

I have received the help and support of many throughout this publication process. I’d like to thank Koo Bohn Chang, who helped make the exhibition of his photographs at the Arles festival a reality. To Choi Jonghyun, I give my thanks for his help in locating the sites captured in the photographs, and for never failing to offer helpful words of advice. A big thanks to Lee Mun-Woong, who graciously composed the article. His words have become a priceless opportunity to meditate on yet undiscovered merits of Han’s photography. And, above all, thanks to everyone who has loved the artist’s work and who supported the making of this book. The Han Youngsoo Foundation will continue to make his name and work known.

Han Sunjung General Director of Han Youngsoo Foundation

The positive support and help of these countless people have given me the courage to prepare a second book of series. Although the idea to publish a series of Han’s work has been on my mind since I first encountered his remaining film and contact sheets, I couldn’t help but worry when it came to finally deciding what the subject of the second installment should be. The decision I eventually reached was “children.”

Once Upon a Time comprises photographs of children from the 1950s and 1960s in Korea. It was an era that, while difficult and hard following the destructive years of Korea War, was also a time of overcoming that pain and the beginning of reconstruction. Even against that backdrop of the times, the children captured in these photographs nevertheless remain positive and pure. This manner of looking at the future through youth is the unique result of the photographer’s eyes. The imagery captures the childhoods of today’s older generation, who reconstructed the country from the ground up.

We added the time and location of each photograph in this book. It is a project that began with piecing together the puzzle of Han’s fragmented memos, stuck at angles on files of film, photo captions and descriptions published in catalogues during his lifetime. It is a process that feels like following in his footsteps. And although it is work that has yet to be completed, the puzzle will be pieced together until the last of the series is finished.

I have received the help and support of many throughout this publication process. I’d like to thank Koo Bohn Chang, who helped make the exhibition of his photographs at the Arles festival a reality. To Choi Jonghyun, I give my thanks for his help in locating the sites captured in the photographs, and for never failing to offer helpful words of advice. A big thanks to Lee Mun-Woong, who graciously composed the article. His words have become a priceless opportunity to meditate on yet undiscovered merits of Han’s photography. And, above all, thanks to everyone who has loved the artist’s work and who supported the making of this book. The Han Youngsoo Foundation will continue to make his name and work known.

Han Sunjung General Director of Han Youngsoo Foundation

한 문화인류학자가 본 한영수의 ‘민속지’ 사진

문화인류학자들은 인간의 삶의 현장을 중요시한다. 인류학이 인간의 행동양식과 사고방식을 포함하는 삶의 총체를 연구하는 학문이기 때문이다. 인간의 삶을 구성하는 부분들은 모두 별개의 영역에 존재하는 것이 아니라 서로 간에 밀접하게 연결되어 있기 때문에 현장을 직접 관찰하지 않고 간접적인 자료에만 의거해서 상상력을 발동해서 현상을 이해하려는 데에는 항시 무리가 따른다. 따라서 인류학자들은 사회문화현상을 연구하는 데에 현장조사를 하면서 현상을 관찰하는 그대로 자세하게 기술하는 방식으로 자료 수집을 한다. 이렇게 현장조사에 의거해서 수집된 자료로 현상을 재구성해서 작성된 문서를 ‘민속지’(民俗誌; ethnography; 또는 민족지)라고 한다. 이 민속지에는 조사의 대상이 되는 사람들이 어떻게 행동하고 어떻게 생각하는지에 대한 비교적 자세한 정보가 기술되어 있어 문화연구를 위한 기본적인 자료로 활용된다.

하지만 사람이 사회문화현상을 관찰하는 데에는 한계가 있다. 같은 현상을 두고도 관찰하는 사람에 따라서 무엇을 보았는지에 대한 내용이 다를 수 있다. 사람들이 어떤 현상을 관찰하는 데에는 어쩔 수 없이 그의 주관이 개입될 수밖에 없다. 사회과학자 역시 예외는 아니다. 실제로 문화인류학 문헌에서 자주 인용되는 로버트 레드필드(Robert Redfield)와 오스카 루이스(Oscar Lewis)의 멕시코 떼뽀스뜰란(Tepoztlan) 연구는 이런 상반된 연구결과의 전형적인 사례이다. 이 두 학자들은 모두 장기간에 걸친 현지연구를 통해서 지역사회의 일상생활이 어떤 식으로 영위되고 있는지를 참여관찰 했다. 레드필드는 떼뽀스뜰란이 매우 정적이며 평화롭고 질서정연한 과거지향의 사회라고 했지만, 루이스의 재조사 결과에 의하면 매우 역동적이고, 멕시코의 근대화 과정에서 걷잡을 수 없는 변화를 경험하고 있는 미래지향적인 사회라는 결론을 내렸다. 물론 두 조사가 1930년대와 1950년대의 20여 년의 시차를 두고 이루어졌다는 점에서 직접적인 비교는 무리일 수가 있다. 그러나 두 사람의 연구에서 한 가지 분명한 것은 연구자의 관점의 차이였다. 레드필드는 사회의 규범적인 측면에서 현상을 파악하려 했던 반면에 루이스는 규범에 구애되지 않은 채 실제로 사람들이 어떻게 생각하고 또 행동하고 있었는지에 초점을 맞추어서 연구한 것이 이런 상반된 결과를 빚어낸 것이다.

현지조사에 나갔던 연구자가 관찰한 바를 자세하게 적어놓은 노트와 그의 기억만으로 ‘민속지’를 작성하는 것이 초기 문화인류학자들의 일반적인 조사연구 방식이었다. 그러나 이제 사진기와 녹음기, 그리고 근래에는 캠코더까지 추가되어 현지조사는 더욱 효과적으로 수행되고 있다. 조사자는 자신이 현지에서 관찰하고 경험했던 바를 연구실로 돌아와서 반복적으로 검토하면서 더욱 심도 있게 연구를 할 수 있게 되었다. 이러한 새로운 장비 중 가장 먼저 등장한 것이 사진기였을 것이다.

흔히들 사진은 ‘객관적’이라고 하지만, 인간의 넓은 시각 속에서 사진의 프레임에 담기는 부분은 불가피하게 촬영하는 사람에의해 선택되는 것이기에 실제로 사진에 담기는 것은 ‘주관적’인 부분이라는 점도 사실이다. 그러나 현지조사 과정에서 실제로 전행되고 있는 상황에 대한 모든 정보를 기억 속에 모두 담는다는 것은 사실상 불가능한 일이다. 카메라는 현상을 있는 그대로 기계적으로 담아 언제나 필요할 때마다 재현할 수 있다는 이점을 지니고 있다. 그런 점에서 사진은 그 존재 자체로 관찰자가 미처 주목하지도 못했던 문화정보를 모두 담고 있는 ‘민속지적인 성격(ethnographicness)’을 지니고 있다. 문화연구에서 특히 사진의 중요성에 대해서 주목한 선구적인 문화인류학자 존 콜리어(John Collier, Jr.)는 사진 한 장에 담긴 문화정보의 양이 얼마나 많은지에 대해서 역설한 [영상인류학: 연구방법으로서의 사진Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method](1967)이라는 책을 저술한 바 있다.

사회문화현상을 구성하는 데에 관여하는 요소는 무수히 많다. 어떤 사람의 특정한 행동을 담은 사진이라고 해도, 그가 어떤 옷을 어떻게 입었으며, 그의 주위에는 어떤 사람이 있기에 그의 행동이 그런 식으로 나타나고 있는가, 또 그 상황이 벌어진 장소가 어떻기에 그의 행동이 그런 식으로 나타나고 있는지 등 모든 사실 그 하나하나가 문화 정보이다. 우리가 일상적으로 보는 것이기에 별로 주목하지 않을 수도 있지만, 어떤 미지의 세계를 깊이 있게 연구한다던가, 마치 수사관 같이 현상을 재구성 하여 사건의 실마리를 풀어내려고 한다면 그 하나하나의 정보가 실로 귀중한 것이다.

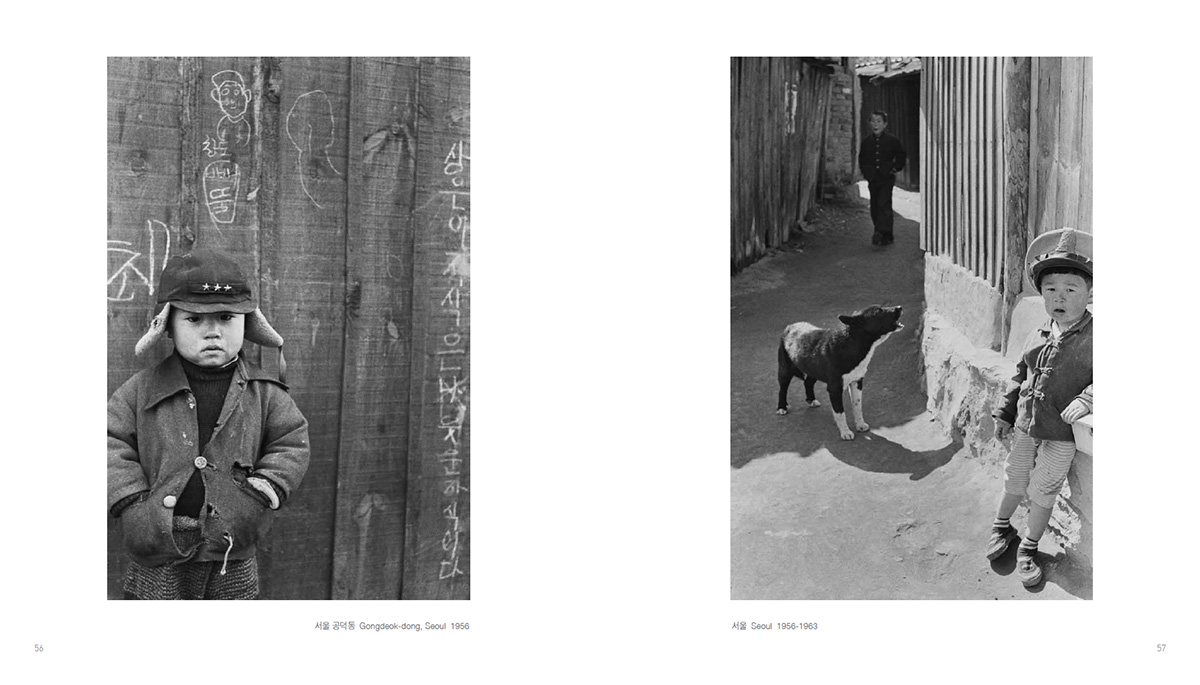

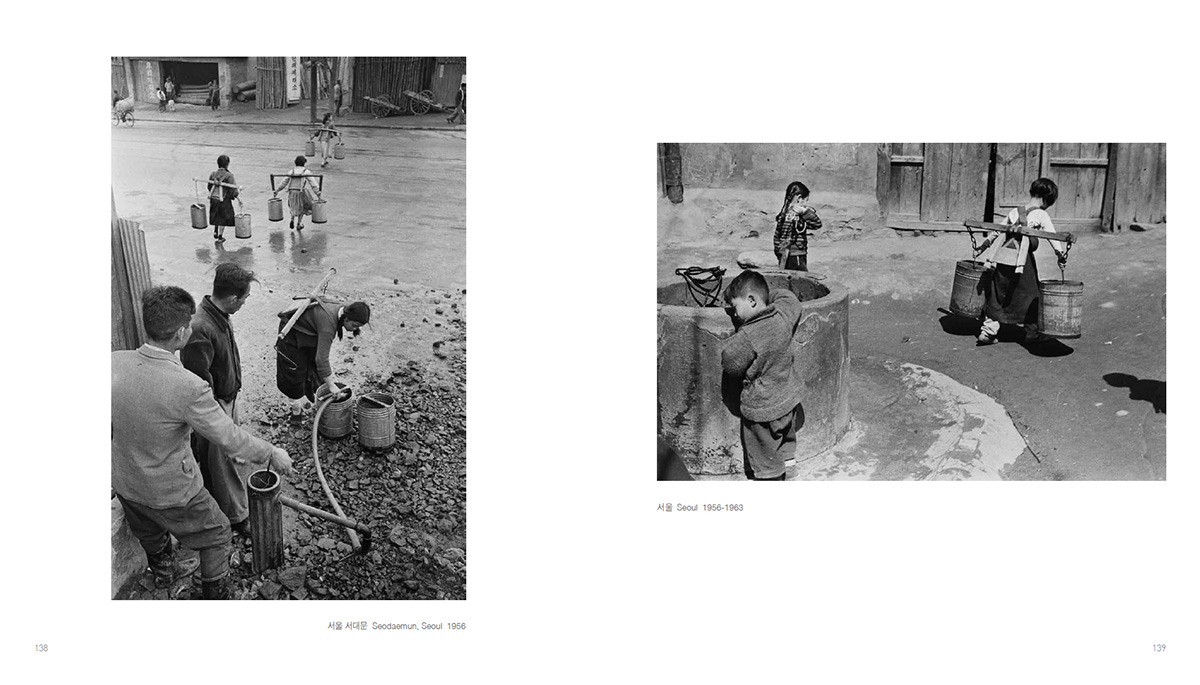

이 사진집은 사진작가 한영수가 남긴 작품들 중에서 어린이들의 모습을 담은 사진들만을 모아 펴낸 것이다. 우리는 21세기의 현재를 살면서 사진작가 한영수의 사진집을 통해 반세기 전의 사진들을 본다. 반세기 전이라면 필자가 고등학교를 다니던 시기였다. 이 책에 실린 사진들은 전혀 연출되지 않은, 현상을 있는 그대로 순간을 포착한 것으로, 카메라의 렌즈를 의식하고 있는 어린이를 찾아보기 힘들다. 이 사진들에 담긴 어린이들의 옷에만 주목해도 우리는 많은 이야기를 끌어낼 수 있을 것이다. 오늘날의 어린이들은 거의 예외 없이 기성복을 입는다. 그러나 반세기 전만 해도 우리네 가정에서는 아이들의 옷을 거의 집에서 직접 만들어서 입혔다. 상류층의 부유한 가정을 제외하고는 시장에서 구입해 입히는 옷은 거의 최소한에 그쳤다. 거기에는 옷을 만드는 데에 필수적인 재단을 위한 패턴이라는 개념도 없었을 것이다. 청소년들의 교복을 제외하고는 어린이들의 옷은 누가 입을 것인지 만을 생각하면서 대충 옷감을 잘라서 집에서 만든 옷들이었다. 그때는 그랬었다. 그리고 지금은 어린이들이 고무신을 신는다는 것은 상상도 할 수 없는 일이지만 당시만 해도 가죽구두나 운동화를 신는다는 것은 거의 상류층에 속하는 어린이들뿐이었다.

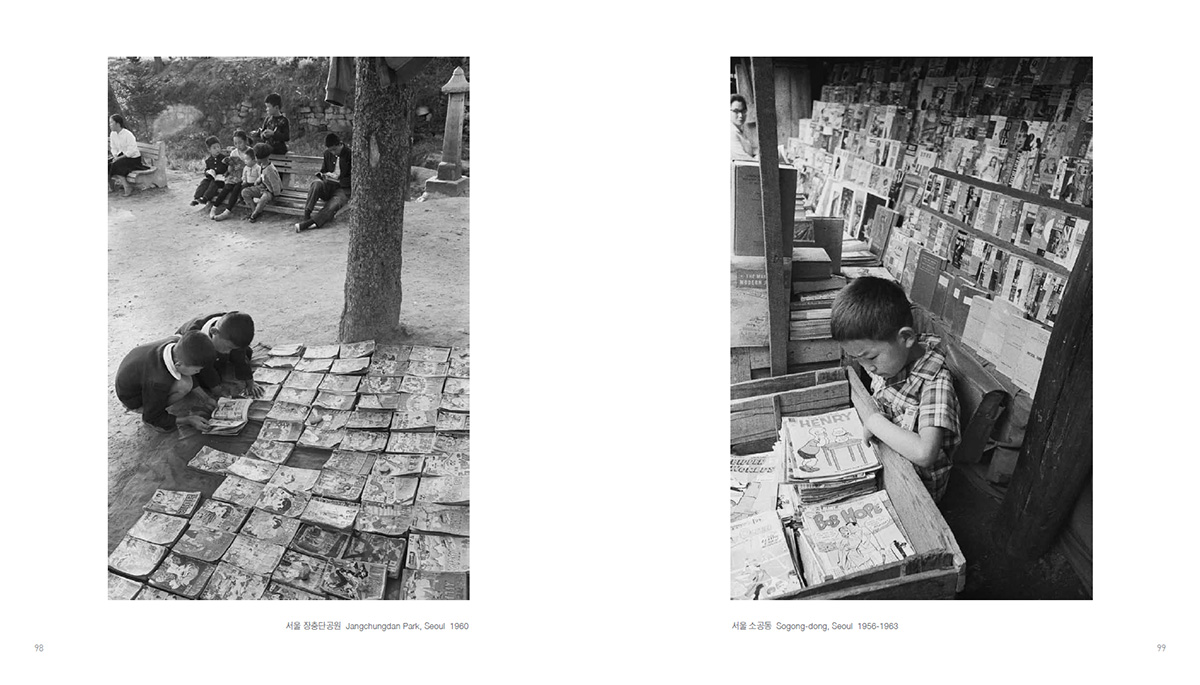

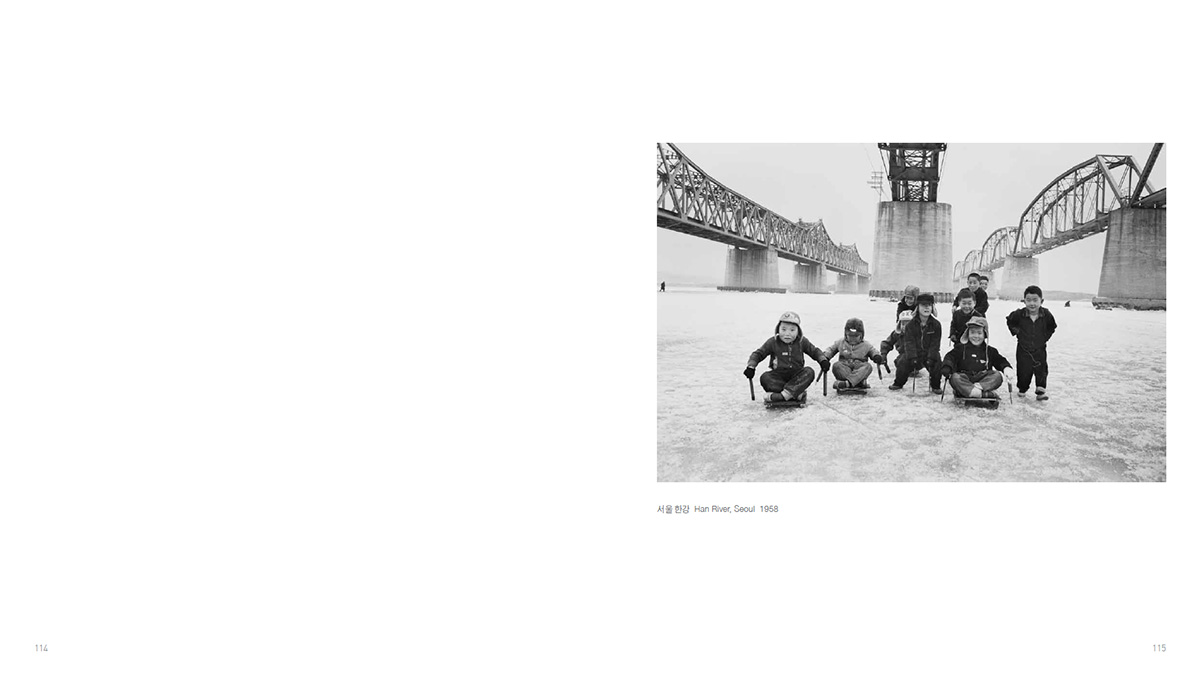

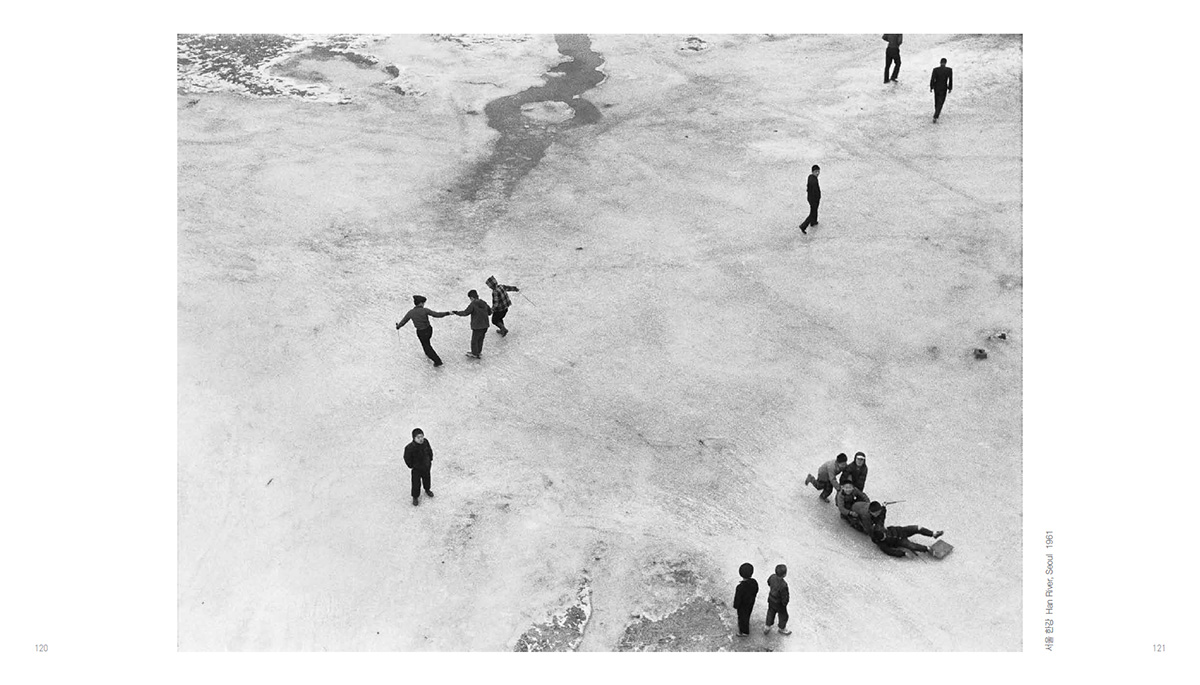

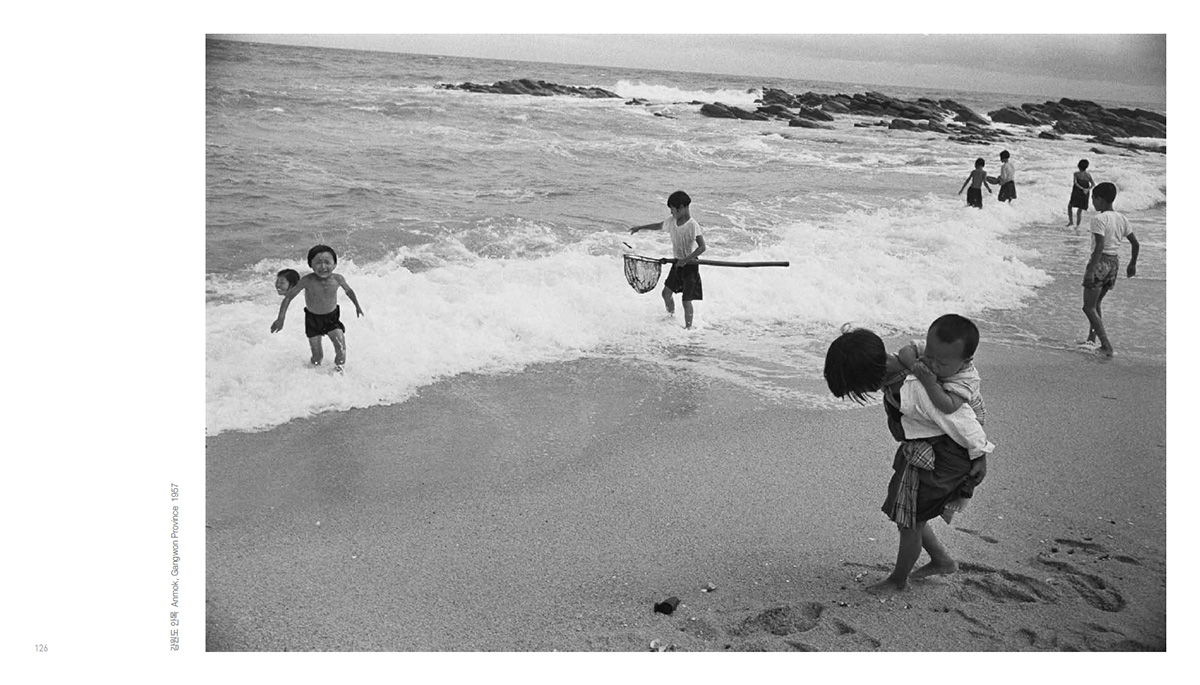

어린이들의 놀이문화를 보여주고 있는 사진들도 적지 않다. 당시는 오늘날과 같이 다양한 장난감이 존재하던 시대가 아니었다. 그 대신 길에 나가면 모든 공간이 놀이터요 놀이기구였고, 손에 잡히는 모든 것이 장난감이었다. 또래끼리 함께 모여서 숨바꼭질을 하는가 하면 세발자전거를 번갈아 타면서 놀고, 여자 아이들은 고무줄놀이를 한다. 냇가에서 빨래하는 어머니 곁에서 꼬마 동생을 돌봐주고 있는 모습, 겨울의 한강에서 친구들과 함께 썰매 타는 아이들, 쪼개져서 떠다니는 얼음 조각을 타고 노는 어린이들, 길에 나와 또래들과 함께 각종 놀이를 즐기는 아이들. 이렇게 함께 커가는 아이들은 마치 한 가족 형제자매와 같은 사이가 되었을 것이다. 길에서 만화책을 펴놓고 영업(?)을 하는 만화방과 그 옆 길가의 벤치에서 만화를 읽는 모습과 동생들을 옆에 앉혀놓고 만화를 읽어주는 언니의 모습은 정겹기도 하다. 울퉁불퉁한 돌계단으로 위험천만해 보이는 가파른 언덕길은 놀이터가 되고, 할아버지를 따라 옆을 걸어서 올라오는 꼬마는 마냥 즐겁기만 하다.

이 모든 것들은 그 시대의 생활상을 생생하게 그리고 있는 문화정보들이다. 관찰자들의 눈으로는 순식간에 일어난 일이라 놓치기 쉬운 사항도 연구실로 돌아와서 다시 검토한다면 정확하게 상황을 파악할 수 있다. 또 사진은 마치 지식정보의 ‘깡통따개’(can-opener)와 같은 역할을 할 수도 있다. 제보자에게 사진을 제시하면서 옆에 있는 사람은 누구이고, 또 어떤 관계의 사람인지, 그 후에 어떤 일이 벌어졌는지 등의 추가적인 정보를 얻어낼 수 있다면 그 사진은 상황의 이해를 위한 귀중한 추가 정보를 제공해줄 수 있는 열쇠가 되는 셈이다.

물론 인류학자들은 이런 사진자료들을 민족지로 활용하기 위해 사진에 관한 메타데이터를 철저하게 조사하여 첨부한다. 나는 1970년대 초에 미국 국립자연사박물관(Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution)에서 일한 적이 있는데, 이때 이 박물관의 인류학 아카이브(Anthropology Archive)에 소장되어 있는 한국 영상자료에 대한 메타데이터를 작성하는 작업을 도운 적이 있다. 구한말 한국인들의 생활을 찍은 사진들이었는데, 한국문화의 어떤 측면을 찍은 사진인지에 관한 정보를 가능한대로 파악하는 작업이었다. 물론 내가 이 사진들에 대한 정확한 메타데이터를 모두 작성할 수는 없었지만, 미국의 박물관 으로서는 이 사진들에 대한 최소한의 정보가 없이는 아무런 가치가 없을 것이기에 이런 작업이 이루어진 것이다. 그러나 애초에 인류학적인 조사를 위한 사진을 촬영한 것이 아닌 사진가 한영수에게 이러한 작업까지 바라는 것은 사실상 무리한 일이다. 그냥 봐서도 쉽게 알 수 있는 정보라고 생각하면서 일상적인 것들에 대해서는 영상기록으로 남기고, 그에 대한 메타데이터를 작성할 필요를 느끼지 않았을지도 모른다.

우리는 일반적으로 우리 앞에서 펼쳐지고 있는 일상적인 것들에 별로 주목하지 않는다. 그러나 사진가 한영수는, 의도했던 의도하지 않았던, 다른 사람들이 ‘하찮은 것’이라고 그냥 스쳐 지나갈 그런 장면들을 포착하여 ‘한국문화의 데이터베이스’에 올려놓았다. 그 결과 이 사진들 속에는 1950년대 후반부터 1960년대 초반까지, 한국전쟁 이후의 특정한 시기에 어린이들이 어떻게 살아왔는지를 드러내는 수많은 문화정보가 담겨 있으며, 그것이 여기에 모아놓은 한영수의 사진들을 굳이 ‘민속지’ 사진이라고 부르고자 하는 이유이기도 하다.

그리고 이렇게 반세기가 지난 후, 지금처럼 시대적인 상황이 너무나도 바뀌었을 때에는 이전에는 어떠했었는지 정보가 필요하다. 그 시기를 살아왔던 사람들에게는 향수를 느끼게 하는 한 장의 사진을 보며, 정보화 시대를 살아가는 지금의 청소년들은 우리나라에도 이런 시대가 있었다는 것에 대해 신기하게 생각할지도 모른다. 사회문화현상은 결코 정태적인 것이 아니며 시대에 따라 끊임없이 변해 간다. 반세기 전의 생활상에 비한다면 오늘날 우리는 풍요로운 삶을 영위하고 있는 것이다. 그러나 오늘의 문화는 갑자기 등장한 것이 아니다. 이 사진집에 모아놓은 ‘민속지 사진들’에서 보는 바와 같은 그런 생활상에서 점진적인 변화를 경험하면서 오늘에 이른 것이다. 이 사진들에는 시대적인 상황이 고스란히 반영되어있다. 정치, 경제, 과학기술의 발전 등을 포함하는 사회문화의 다양한 측면에서 종합적으로 고려해야만 이 사진들이 담고 있는 맥락을 설득력 있게 읽어낼 수 있을 것이다. 이런 의미에서도 한영수의 ‘민속지 사진들’은 우리 문화의 진화과정을 생생하게 보여주는 사다리 역할을 하는 귀중한 자료임이 틀림없으며, 이 사진들은 일반 사람들의 눈으로는 놓쳐버리기 쉬운 귀중한 문화정보들을 담고 있기에 시간이 갈수록 더욱 빛을 발할 것이다.

이 문 웅 서울대학교 명예교수, 인류학

문화인류학자들은 인간의 삶의 현장을 중요시한다. 인류학이 인간의 행동양식과 사고방식을 포함하는 삶의 총체를 연구하는 학문이기 때문이다. 인간의 삶을 구성하는 부분들은 모두 별개의 영역에 존재하는 것이 아니라 서로 간에 밀접하게 연결되어 있기 때문에 현장을 직접 관찰하지 않고 간접적인 자료에만 의거해서 상상력을 발동해서 현상을 이해하려는 데에는 항시 무리가 따른다. 따라서 인류학자들은 사회문화현상을 연구하는 데에 현장조사를 하면서 현상을 관찰하는 그대로 자세하게 기술하는 방식으로 자료 수집을 한다. 이렇게 현장조사에 의거해서 수집된 자료로 현상을 재구성해서 작성된 문서를 ‘민속지’(民俗誌; ethnography; 또는 민족지)라고 한다. 이 민속지에는 조사의 대상이 되는 사람들이 어떻게 행동하고 어떻게 생각하는지에 대한 비교적 자세한 정보가 기술되어 있어 문화연구를 위한 기본적인 자료로 활용된다.

하지만 사람이 사회문화현상을 관찰하는 데에는 한계가 있다. 같은 현상을 두고도 관찰하는 사람에 따라서 무엇을 보았는지에 대한 내용이 다를 수 있다. 사람들이 어떤 현상을 관찰하는 데에는 어쩔 수 없이 그의 주관이 개입될 수밖에 없다. 사회과학자 역시 예외는 아니다. 실제로 문화인류학 문헌에서 자주 인용되는 로버트 레드필드(Robert Redfield)와 오스카 루이스(Oscar Lewis)의 멕시코 떼뽀스뜰란(Tepoztlan) 연구는 이런 상반된 연구결과의 전형적인 사례이다. 이 두 학자들은 모두 장기간에 걸친 현지연구를 통해서 지역사회의 일상생활이 어떤 식으로 영위되고 있는지를 참여관찰 했다. 레드필드는 떼뽀스뜰란이 매우 정적이며 평화롭고 질서정연한 과거지향의 사회라고 했지만, 루이스의 재조사 결과에 의하면 매우 역동적이고, 멕시코의 근대화 과정에서 걷잡을 수 없는 변화를 경험하고 있는 미래지향적인 사회라는 결론을 내렸다. 물론 두 조사가 1930년대와 1950년대의 20여 년의 시차를 두고 이루어졌다는 점에서 직접적인 비교는 무리일 수가 있다. 그러나 두 사람의 연구에서 한 가지 분명한 것은 연구자의 관점의 차이였다. 레드필드는 사회의 규범적인 측면에서 현상을 파악하려 했던 반면에 루이스는 규범에 구애되지 않은 채 실제로 사람들이 어떻게 생각하고 또 행동하고 있었는지에 초점을 맞추어서 연구한 것이 이런 상반된 결과를 빚어낸 것이다.

현지조사에 나갔던 연구자가 관찰한 바를 자세하게 적어놓은 노트와 그의 기억만으로 ‘민속지’를 작성하는 것이 초기 문화인류학자들의 일반적인 조사연구 방식이었다. 그러나 이제 사진기와 녹음기, 그리고 근래에는 캠코더까지 추가되어 현지조사는 더욱 효과적으로 수행되고 있다. 조사자는 자신이 현지에서 관찰하고 경험했던 바를 연구실로 돌아와서 반복적으로 검토하면서 더욱 심도 있게 연구를 할 수 있게 되었다. 이러한 새로운 장비 중 가장 먼저 등장한 것이 사진기였을 것이다.

흔히들 사진은 ‘객관적’이라고 하지만, 인간의 넓은 시각 속에서 사진의 프레임에 담기는 부분은 불가피하게 촬영하는 사람에의해 선택되는 것이기에 실제로 사진에 담기는 것은 ‘주관적’인 부분이라는 점도 사실이다. 그러나 현지조사 과정에서 실제로 전행되고 있는 상황에 대한 모든 정보를 기억 속에 모두 담는다는 것은 사실상 불가능한 일이다. 카메라는 현상을 있는 그대로 기계적으로 담아 언제나 필요할 때마다 재현할 수 있다는 이점을 지니고 있다. 그런 점에서 사진은 그 존재 자체로 관찰자가 미처 주목하지도 못했던 문화정보를 모두 담고 있는 ‘민속지적인 성격(ethnographicness)’을 지니고 있다. 문화연구에서 특히 사진의 중요성에 대해서 주목한 선구적인 문화인류학자 존 콜리어(John Collier, Jr.)는 사진 한 장에 담긴 문화정보의 양이 얼마나 많은지에 대해서 역설한 [영상인류학: 연구방법으로서의 사진Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method](1967)이라는 책을 저술한 바 있다.

사회문화현상을 구성하는 데에 관여하는 요소는 무수히 많다. 어떤 사람의 특정한 행동을 담은 사진이라고 해도, 그가 어떤 옷을 어떻게 입었으며, 그의 주위에는 어떤 사람이 있기에 그의 행동이 그런 식으로 나타나고 있는가, 또 그 상황이 벌어진 장소가 어떻기에 그의 행동이 그런 식으로 나타나고 있는지 등 모든 사실 그 하나하나가 문화 정보이다. 우리가 일상적으로 보는 것이기에 별로 주목하지 않을 수도 있지만, 어떤 미지의 세계를 깊이 있게 연구한다던가, 마치 수사관 같이 현상을 재구성 하여 사건의 실마리를 풀어내려고 한다면 그 하나하나의 정보가 실로 귀중한 것이다.

이 사진집은 사진작가 한영수가 남긴 작품들 중에서 어린이들의 모습을 담은 사진들만을 모아 펴낸 것이다. 우리는 21세기의 현재를 살면서 사진작가 한영수의 사진집을 통해 반세기 전의 사진들을 본다. 반세기 전이라면 필자가 고등학교를 다니던 시기였다. 이 책에 실린 사진들은 전혀 연출되지 않은, 현상을 있는 그대로 순간을 포착한 것으로, 카메라의 렌즈를 의식하고 있는 어린이를 찾아보기 힘들다. 이 사진들에 담긴 어린이들의 옷에만 주목해도 우리는 많은 이야기를 끌어낼 수 있을 것이다. 오늘날의 어린이들은 거의 예외 없이 기성복을 입는다. 그러나 반세기 전만 해도 우리네 가정에서는 아이들의 옷을 거의 집에서 직접 만들어서 입혔다. 상류층의 부유한 가정을 제외하고는 시장에서 구입해 입히는 옷은 거의 최소한에 그쳤다. 거기에는 옷을 만드는 데에 필수적인 재단을 위한 패턴이라는 개념도 없었을 것이다. 청소년들의 교복을 제외하고는 어린이들의 옷은 누가 입을 것인지 만을 생각하면서 대충 옷감을 잘라서 집에서 만든 옷들이었다. 그때는 그랬었다. 그리고 지금은 어린이들이 고무신을 신는다는 것은 상상도 할 수 없는 일이지만 당시만 해도 가죽구두나 운동화를 신는다는 것은 거의 상류층에 속하는 어린이들뿐이었다.

어린이들의 놀이문화를 보여주고 있는 사진들도 적지 않다. 당시는 오늘날과 같이 다양한 장난감이 존재하던 시대가 아니었다. 그 대신 길에 나가면 모든 공간이 놀이터요 놀이기구였고, 손에 잡히는 모든 것이 장난감이었다. 또래끼리 함께 모여서 숨바꼭질을 하는가 하면 세발자전거를 번갈아 타면서 놀고, 여자 아이들은 고무줄놀이를 한다. 냇가에서 빨래하는 어머니 곁에서 꼬마 동생을 돌봐주고 있는 모습, 겨울의 한강에서 친구들과 함께 썰매 타는 아이들, 쪼개져서 떠다니는 얼음 조각을 타고 노는 어린이들, 길에 나와 또래들과 함께 각종 놀이를 즐기는 아이들. 이렇게 함께 커가는 아이들은 마치 한 가족 형제자매와 같은 사이가 되었을 것이다. 길에서 만화책을 펴놓고 영업(?)을 하는 만화방과 그 옆 길가의 벤치에서 만화를 읽는 모습과 동생들을 옆에 앉혀놓고 만화를 읽어주는 언니의 모습은 정겹기도 하다. 울퉁불퉁한 돌계단으로 위험천만해 보이는 가파른 언덕길은 놀이터가 되고, 할아버지를 따라 옆을 걸어서 올라오는 꼬마는 마냥 즐겁기만 하다.

이 모든 것들은 그 시대의 생활상을 생생하게 그리고 있는 문화정보들이다. 관찰자들의 눈으로는 순식간에 일어난 일이라 놓치기 쉬운 사항도 연구실로 돌아와서 다시 검토한다면 정확하게 상황을 파악할 수 있다. 또 사진은 마치 지식정보의 ‘깡통따개’(can-opener)와 같은 역할을 할 수도 있다. 제보자에게 사진을 제시하면서 옆에 있는 사람은 누구이고, 또 어떤 관계의 사람인지, 그 후에 어떤 일이 벌어졌는지 등의 추가적인 정보를 얻어낼 수 있다면 그 사진은 상황의 이해를 위한 귀중한 추가 정보를 제공해줄 수 있는 열쇠가 되는 셈이다.

물론 인류학자들은 이런 사진자료들을 민족지로 활용하기 위해 사진에 관한 메타데이터를 철저하게 조사하여 첨부한다. 나는 1970년대 초에 미국 국립자연사박물관(Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution)에서 일한 적이 있는데, 이때 이 박물관의 인류학 아카이브(Anthropology Archive)에 소장되어 있는 한국 영상자료에 대한 메타데이터를 작성하는 작업을 도운 적이 있다. 구한말 한국인들의 생활을 찍은 사진들이었는데, 한국문화의 어떤 측면을 찍은 사진인지에 관한 정보를 가능한대로 파악하는 작업이었다. 물론 내가 이 사진들에 대한 정확한 메타데이터를 모두 작성할 수는 없었지만, 미국의 박물관 으로서는 이 사진들에 대한 최소한의 정보가 없이는 아무런 가치가 없을 것이기에 이런 작업이 이루어진 것이다. 그러나 애초에 인류학적인 조사를 위한 사진을 촬영한 것이 아닌 사진가 한영수에게 이러한 작업까지 바라는 것은 사실상 무리한 일이다. 그냥 봐서도 쉽게 알 수 있는 정보라고 생각하면서 일상적인 것들에 대해서는 영상기록으로 남기고, 그에 대한 메타데이터를 작성할 필요를 느끼지 않았을지도 모른다.

우리는 일반적으로 우리 앞에서 펼쳐지고 있는 일상적인 것들에 별로 주목하지 않는다. 그러나 사진가 한영수는, 의도했던 의도하지 않았던, 다른 사람들이 ‘하찮은 것’이라고 그냥 스쳐 지나갈 그런 장면들을 포착하여 ‘한국문화의 데이터베이스’에 올려놓았다. 그 결과 이 사진들 속에는 1950년대 후반부터 1960년대 초반까지, 한국전쟁 이후의 특정한 시기에 어린이들이 어떻게 살아왔는지를 드러내는 수많은 문화정보가 담겨 있으며, 그것이 여기에 모아놓은 한영수의 사진들을 굳이 ‘민속지’ 사진이라고 부르고자 하는 이유이기도 하다.

그리고 이렇게 반세기가 지난 후, 지금처럼 시대적인 상황이 너무나도 바뀌었을 때에는 이전에는 어떠했었는지 정보가 필요하다. 그 시기를 살아왔던 사람들에게는 향수를 느끼게 하는 한 장의 사진을 보며, 정보화 시대를 살아가는 지금의 청소년들은 우리나라에도 이런 시대가 있었다는 것에 대해 신기하게 생각할지도 모른다. 사회문화현상은 결코 정태적인 것이 아니며 시대에 따라 끊임없이 변해 간다. 반세기 전의 생활상에 비한다면 오늘날 우리는 풍요로운 삶을 영위하고 있는 것이다. 그러나 오늘의 문화는 갑자기 등장한 것이 아니다. 이 사진집에 모아놓은 ‘민속지 사진들’에서 보는 바와 같은 그런 생활상에서 점진적인 변화를 경험하면서 오늘에 이른 것이다. 이 사진들에는 시대적인 상황이 고스란히 반영되어있다. 정치, 경제, 과학기술의 발전 등을 포함하는 사회문화의 다양한 측면에서 종합적으로 고려해야만 이 사진들이 담고 있는 맥락을 설득력 있게 읽어낼 수 있을 것이다. 이런 의미에서도 한영수의 ‘민속지 사진들’은 우리 문화의 진화과정을 생생하게 보여주는 사다리 역할을 하는 귀중한 자료임이 틀림없으며, 이 사진들은 일반 사람들의 눈으로는 놓쳐버리기 쉬운 귀중한 문화정보들을 담고 있기에 시간이 갈수록 더욱 빛을 발할 것이다.

A Cultural Anthropologist’s

Take on Han Youngsoo’s ‘Ethnographic’ Photographs

Cultural anthropologists focus on the field of human life. This is because anthropology is a study of man’s livelihood as a whole, including his way of thinking and behavioral patterns. It is always difficult to understand cultural phenomena without any field observation but only based upon second-hand data and imagination, since the parts that comprise a culture do not exist in separate domains each but are intimately inter-connected. Thus, anthropologists collect data by carefully observing and recording the details during fieldwork in order to conduct their research. The text they write as a reconstruction of the cultural phenomena collected through fieldwork is known as an “ethnography.” The detailed information regarding how the subjects of the fieldwork behave and think is utilized as basic information for cultural research.

But there is a limit to people observing socio-cultural phenomena. Depending on the person, the content of the observation may differ even within the same instance. A person’s subjectivity cannot help but intervene. Social scientists are no exception. The anthropological studies on Tepoztlán, Mexico, by Robert Redfield and Oscar Lewis often quoted in anthropology literature are a typical example of these sort of conflicting research results. The two scholars separately observed how everyday life in the regional communities operated, through yearlong field research. Redfield said Tepoztlán was quite a static, peaceful and orderly society oriented toward the past, but according to Lewis’ reexamination, he concluded it was an extremely dynamic, future-oriented society that had been experiencing uncontrollable transformation in the process of Mexico’s period of modernization. Of course, it’s difficult to directly compare the studies, as the two scholars’ work was completed 20 years apart in the 1930s and 1950s. However, one thing that is clear in the two works is the difference between the researchers’ point of view. This conflict arose from the fact that while Redfield tried to investigate from a socially normative angle, Lewis, on the other hand, researched based on how people were actually thinking and behaving rather than insisting on the social norm.

The early cultural anthropologists were, in general, writing their ethnographies based solely on their memories and field-notes taken meticulously during their fieldwork. Now, however, with the advancement of technology, fieldwork is conducted in a much more efficient manner. Fieldworkers can perform much more in-depth research by returning to recordings based on what they had observed and experienced, whenever they want to do so. Among the first of these revelatory equipments was the camera.

Although photographs are ordinarily considered to be “objective,” it is also true that here are “subjective” elements, given that whatever is captured within a frame is inevitably selected by the photographer. It is actually impossible to capture by memory all the information pertaining to a situation as it happened in the process of fieldwork. The camera possesses the advantage of being able to reproduce mechanically the exact conditions that are captured at any given moment. In that respect, photographs in and of themselves possess a sense of ‘ethnographicness’ that contain all the cultural information unable to be recognized by the observer. John Collier, Jr., a pioneering cultural anthropologist who stressed the importance of photography in cultural research, authored a book titled Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method (1967), in which he emphasized exactly how much cultural information could be found within a single photograph.

There are countless elements concerned with the composition of a socio-cultural state. Even within a photograph that captures a particular act by a specific person, what clothing is being worn, what people are seen in the vicinity, what form that act is taking, and what location the scene is unfolding in are all individual pieces of information. Although these things might seem unremarkable in the context of our daily lives, they become truly valuable fragments of data, whether comprehensively researching some unknown world thoroughly or perhaps uncovering clues to an incident like a detective.

This book is a selection of works that capture the images of children, selected from the oeuvres of photographer Han Youngsoo. Through this collection, we are privy to images from half a century ago, even as we live in today’s 21st century. Fifty years ago was when this writer was a high school student. It is hard to find amongst the images a child who is aware of the camera lens. These photographs are not posed, but capture the exact moment of an exact space in time.

It is possible to unravel countless stories here, even if we focus solely on the clothing worn by the photographs’ subjects. Children today wear ready-made clothing, almost without exception. However, just a half century ago almost all clothing was made by hand, at home. Except for the affluent families of the upper classes, very few wore clothing purchased at market. It’s likely the concept of a pattern on which to base an item when making clothing was also rare. Apart from the school uniforms of adolescents, the homemade outfits were cut roughly the right size, as decided by the maker, and made specifically for the wearer. It was the way of the times. Although it’s hard to imagine children wearing shoes made of rubber today, at the time the idea of wearing leather shoes or sneakers was something only upper class families could dream.

There are many photographs that show the culture of children’s play. It was not an era when a diversity of toys existed. Instead, anything that could be held in one’s hands became a toy, and all the space in the outdoors the playground. Children gravitated to their peers, playing hide-and-seek, taking turns on a tricycle, or jumping rope. Children came out on the street and played in groups, rode on pieces of ice in winter, sled on top of the frozen Han River, and watched over their younger siblings while their mothers washed laundry in the stream. These children grew together, close enough to almost be called brothers and sisters of a single family. The image of an entrepreneur laying out a spread of comics next to the side of the road, a child reading comics on a nearby bench, and a sister reading next to her younger sibling are heartwarming. The steep, hilly path that looks treacherous with its jagged stone steps becomes yet another playground, and the child walking up alongside his grandfather is elated. All of these are pieces of cultural information drawn vividly of life in a different time. These are moments that occur instantaneously, easily missed by even a careful observer’s eye, but able to be read accurately upon returning to the material and reexamined. Additionally, photographs take on the role of something similar to a “can opener” of knowledge information. A photograph can become something like a key that offers additional, valuable information in order to understand cultural phenomena, when an informant is shown an image and asked who this person is, or what the relationship between these two people are, and what happened between them after the photo was taken. Of course, in order to use these photographic materials as ethnographies, anthropologists must refer to and thoroughly investigate the metadata related to the image. In the early 1970s I worked at the National Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian Institution, assisting in recording the metadata for Korean visual materials in the Anthropology Archive. These were photographs taken of livelihood of the Koreans in the late Choseon Dynasty, and my work involved describing as much information as possible about what aspects of Korean culture the photographs showed. Although, of course, I wasn’t able to record all the exact metadata, the work was pursued because without at least a minimum amount of information about the images, the photographs were worthless. It is for this reason that it is difficult to ask of Han this sort of information, when his photographs were not initially taken for some anthropological study anyway. It is possible he didn’t even feel the necessity to write down all the information regarding each image, instead leaving it as visual record of everyday things as he believed it to be information easily accessible upon viewing.

We rarely pay attention to the cultural phenomena that unfold right before us in everyday life. Yet the photographer Han Youngsoo captured, whether he intended it or not, the scenes that others would overlook as banal, unintentionally creating a ‘Korean cultural database.’ His photographs are filled with countless quantities of cultural information, on how the children of the post-Korean War era lived, during the late 1950s and early 1960s. It is the reason why I would like to refer Han’s works collected here as ‘ethnographic photographs.’

Half a century has passed, since these photographs were taken. Today’s social circumstances have changed drastically, and we need information on how things were in the past. And it’s possible that today’s teenagers in this information age will think it is interesting to know that there was this period in our past, as they look at each of the photographs that remind the people who lived those days of what it was like. Socio-cultural phenomena are, ultimately, not static, but constantly changing through time. Compared to the past 50 years, today we live in an era of affluence. However, today’s culture isn’t something that appeared out of nowhere. We are here today through the gradual changes we experienced from the life now visible in the ethnographic photographs collected in the book. Contemporary circumstances are reflected in these photographs. It is would be possible to read convincingly the cultural context found in the images, when we consider the diverse socio-cultural aspects, including developments in politics, economy, science and technology, as an interacting and interconnected whole. In this respect as well, Han’s ethnographic photographs are most assuredly a valuable resource that is like a ladder that demonstrates our culture’s process of evolution. And they will become increasingly vital as time goes on, for they retain within cultural information that is easily overlooked by the average onlooker.

Take on Han Youngsoo’s ‘Ethnographic’ Photographs

Lee Mun-Woong

Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, Seoul National University

Cultural anthropologists focus on the field of human life. This is because anthropology is a study of man’s livelihood as a whole, including his way of thinking and behavioral patterns. It is always difficult to understand cultural phenomena without any field observation but only based upon second-hand data and imagination, since the parts that comprise a culture do not exist in separate domains each but are intimately inter-connected. Thus, anthropologists collect data by carefully observing and recording the details during fieldwork in order to conduct their research. The text they write as a reconstruction of the cultural phenomena collected through fieldwork is known as an “ethnography.” The detailed information regarding how the subjects of the fieldwork behave and think is utilized as basic information for cultural research.

But there is a limit to people observing socio-cultural phenomena. Depending on the person, the content of the observation may differ even within the same instance. A person’s subjectivity cannot help but intervene. Social scientists are no exception. The anthropological studies on Tepoztlán, Mexico, by Robert Redfield and Oscar Lewis often quoted in anthropology literature are a typical example of these sort of conflicting research results. The two scholars separately observed how everyday life in the regional communities operated, through yearlong field research. Redfield said Tepoztlán was quite a static, peaceful and orderly society oriented toward the past, but according to Lewis’ reexamination, he concluded it was an extremely dynamic, future-oriented society that had been experiencing uncontrollable transformation in the process of Mexico’s period of modernization. Of course, it’s difficult to directly compare the studies, as the two scholars’ work was completed 20 years apart in the 1930s and 1950s. However, one thing that is clear in the two works is the difference between the researchers’ point of view. This conflict arose from the fact that while Redfield tried to investigate from a socially normative angle, Lewis, on the other hand, researched based on how people were actually thinking and behaving rather than insisting on the social norm.

The early cultural anthropologists were, in general, writing their ethnographies based solely on their memories and field-notes taken meticulously during their fieldwork. Now, however, with the advancement of technology, fieldwork is conducted in a much more efficient manner. Fieldworkers can perform much more in-depth research by returning to recordings based on what they had observed and experienced, whenever they want to do so. Among the first of these revelatory equipments was the camera.

Although photographs are ordinarily considered to be “objective,” it is also true that here are “subjective” elements, given that whatever is captured within a frame is inevitably selected by the photographer. It is actually impossible to capture by memory all the information pertaining to a situation as it happened in the process of fieldwork. The camera possesses the advantage of being able to reproduce mechanically the exact conditions that are captured at any given moment. In that respect, photographs in and of themselves possess a sense of ‘ethnographicness’ that contain all the cultural information unable to be recognized by the observer. John Collier, Jr., a pioneering cultural anthropologist who stressed the importance of photography in cultural research, authored a book titled Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method (1967), in which he emphasized exactly how much cultural information could be found within a single photograph.

There are countless elements concerned with the composition of a socio-cultural state. Even within a photograph that captures a particular act by a specific person, what clothing is being worn, what people are seen in the vicinity, what form that act is taking, and what location the scene is unfolding in are all individual pieces of information. Although these things might seem unremarkable in the context of our daily lives, they become truly valuable fragments of data, whether comprehensively researching some unknown world thoroughly or perhaps uncovering clues to an incident like a detective.

This book is a selection of works that capture the images of children, selected from the oeuvres of photographer Han Youngsoo. Through this collection, we are privy to images from half a century ago, even as we live in today’s 21st century. Fifty years ago was when this writer was a high school student. It is hard to find amongst the images a child who is aware of the camera lens. These photographs are not posed, but capture the exact moment of an exact space in time.

It is possible to unravel countless stories here, even if we focus solely on the clothing worn by the photographs’ subjects. Children today wear ready-made clothing, almost without exception. However, just a half century ago almost all clothing was made by hand, at home. Except for the affluent families of the upper classes, very few wore clothing purchased at market. It’s likely the concept of a pattern on which to base an item when making clothing was also rare. Apart from the school uniforms of adolescents, the homemade outfits were cut roughly the right size, as decided by the maker, and made specifically for the wearer. It was the way of the times. Although it’s hard to imagine children wearing shoes made of rubber today, at the time the idea of wearing leather shoes or sneakers was something only upper class families could dream.

There are many photographs that show the culture of children’s play. It was not an era when a diversity of toys existed. Instead, anything that could be held in one’s hands became a toy, and all the space in the outdoors the playground. Children gravitated to their peers, playing hide-and-seek, taking turns on a tricycle, or jumping rope. Children came out on the street and played in groups, rode on pieces of ice in winter, sled on top of the frozen Han River, and watched over their younger siblings while their mothers washed laundry in the stream. These children grew together, close enough to almost be called brothers and sisters of a single family. The image of an entrepreneur laying out a spread of comics next to the side of the road, a child reading comics on a nearby bench, and a sister reading next to her younger sibling are heartwarming. The steep, hilly path that looks treacherous with its jagged stone steps becomes yet another playground, and the child walking up alongside his grandfather is elated. All of these are pieces of cultural information drawn vividly of life in a different time. These are moments that occur instantaneously, easily missed by even a careful observer’s eye, but able to be read accurately upon returning to the material and reexamined. Additionally, photographs take on the role of something similar to a “can opener” of knowledge information. A photograph can become something like a key that offers additional, valuable information in order to understand cultural phenomena, when an informant is shown an image and asked who this person is, or what the relationship between these two people are, and what happened between them after the photo was taken. Of course, in order to use these photographic materials as ethnographies, anthropologists must refer to and thoroughly investigate the metadata related to the image. In the early 1970s I worked at the National Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian Institution, assisting in recording the metadata for Korean visual materials in the Anthropology Archive. These were photographs taken of livelihood of the Koreans in the late Choseon Dynasty, and my work involved describing as much information as possible about what aspects of Korean culture the photographs showed. Although, of course, I wasn’t able to record all the exact metadata, the work was pursued because without at least a minimum amount of information about the images, the photographs were worthless. It is for this reason that it is difficult to ask of Han this sort of information, when his photographs were not initially taken for some anthropological study anyway. It is possible he didn’t even feel the necessity to write down all the information regarding each image, instead leaving it as visual record of everyday things as he believed it to be information easily accessible upon viewing.

We rarely pay attention to the cultural phenomena that unfold right before us in everyday life. Yet the photographer Han Youngsoo captured, whether he intended it or not, the scenes that others would overlook as banal, unintentionally creating a ‘Korean cultural database.’ His photographs are filled with countless quantities of cultural information, on how the children of the post-Korean War era lived, during the late 1950s and early 1960s. It is the reason why I would like to refer Han’s works collected here as ‘ethnographic photographs.’

Half a century has passed, since these photographs were taken. Today’s social circumstances have changed drastically, and we need information on how things were in the past. And it’s possible that today’s teenagers in this information age will think it is interesting to know that there was this period in our past, as they look at each of the photographs that remind the people who lived those days of what it was like. Socio-cultural phenomena are, ultimately, not static, but constantly changing through time. Compared to the past 50 years, today we live in an era of affluence. However, today’s culture isn’t something that appeared out of nowhere. We are here today through the gradual changes we experienced from the life now visible in the ethnographic photographs collected in the book. Contemporary circumstances are reflected in these photographs. It is would be possible to read convincingly the cultural context found in the images, when we consider the diverse socio-cultural aspects, including developments in politics, economy, science and technology, as an interacting and interconnected whole. In this respect as well, Han’s ethnographic photographs are most assuredly a valuable resource that is like a ladder that demonstrates our culture’s process of evolution. And they will become increasingly vital as time goes on, for they retain within cultural information that is easily overlooked by the average onlooker.

한 영 수 韓 榮 洙

1933 경기도 개성출생

1958 신선회 입회(한국 최초 사진연구회)

0000 한국사진작가협회 입회

0000 한국사진작가협회 총무 선임

0000 일본 “세계사진연감”에 [계시]수록

1959 한국사진작가협회 부회장 선임

0000 한국문화단체총연합회 중앙위원

0000 한국미술가협회 사진부 회원

1960 일본 “세계사진연감”에 [소녀]수록

1961 영국 “국제사진연감”에 [골목소녀]수록

1962 한국창작사진가협회 대표위원

0000 한국상업사진가협회 창립위원

1966 광고사진스튜디오 “한영수사진연구소”설립

1968 조선일보 광고대상 수상

0000 중앙일보 광고대상 수상 (영진약품광고)

1970 연세대학교 경영대학원 졸업

1973 스위스 “포토그라피스 연감”에 전자광고 수록(삼성전자 기획광고)

1975 스위스 “그라피스포스터 연감”에 화장품광고 포스터 수록(태평양화학)

1977 동아일보 광고대상 최우수상(녹십자 기업 PR광고)

0000 스위스 “그라피스포스터 연감”에 화장품광고 포스터 수록(태평양화학)

1985 사진라이브러리 “포토뱅크”창업

1990 동아일보사 주최 국제사진전 심사위원장

1991 대한민국사진전 심사위원장

0000 한국사진작가협회 자문위원

0000 한국광고사진가협회 고문

1999 올해의 문화인상 수상

0000 별세

개인전

1986 ‘아름다운 우리강산’ 디자인포장센터 / 서울, 한국

1988 ‘우리강산’ L.A 한국문화원초청전 / L.A, 미국

1999 “MESTER”(마에스트로) 헝가리 사진박물관초대전 MAI MANO

(Hungarian House of Photography)/ 부다페스트, 헝가리

그룹전

2006 ‘Korean New Days’ 슬로바키아사진축제 / 브라티슬라바, 슬로바키아

2008 ‘동강사진축제’ 동강사진 박물관 소장전 / 동강, 강원도

2008 ‘현대사진60년전’ 한국현대미술관 / 서울, 한국

2008 ‘한강르네상스전’ 한강시민사업본부 / 서울, 한국

2008 ‘숨겨진 4인전’ 대구사진비엔날레 / 대구, 한국

2009 ‘광화문’ 서울역사박물관 / 서울, 한국

2009 ‘한강르네상스’ 한강시민사업본부 / 서울, 한국

2012 ‘삶의 궤적’ 코리아 소사이어티 / 뉴욕, 미국

2014 ‘디스커버리어워드’, 아를포토페스티벌 / 아를, 프랑스

2014 ‘VIP 1950~60: 빈티지 사진’, 서울시립미술관 북서울 미술관 / 서울, 한국

2015 ‘LA NUIT DE LA PHOTO(사진의 밤)’ / 라쇼드퐁, 스위스

작품집

1986 “우리강산” / 열화당

1987 “삶” / 신태양사

1990 “내가자란 서울” (글.어효선 사진.한영수) / 대원사

2014 “서울모던타임즈” / 한스그라픽

컬렉션

헝가리 사진박물관

서울시립미술관

동강사진박물관

서울역사박물관

1933 경기도 개성출생

1958 신선회 입회(한국 최초 사진연구회)

0000 한국사진작가협회 입회

0000 한국사진작가협회 총무 선임

0000 일본 “세계사진연감”에 [계시]수록

1959 한국사진작가협회 부회장 선임

0000 한국문화단체총연합회 중앙위원

0000 한국미술가협회 사진부 회원

1960 일본 “세계사진연감”에 [소녀]수록

1961 영국 “국제사진연감”에 [골목소녀]수록

1962 한국창작사진가협회 대표위원

0000 한국상업사진가협회 창립위원

1966 광고사진스튜디오 “한영수사진연구소”설립

1968 조선일보 광고대상 수상

0000 중앙일보 광고대상 수상 (영진약품광고)

1970 연세대학교 경영대학원 졸업

1973 스위스 “포토그라피스 연감”에 전자광고 수록(삼성전자 기획광고)

1975 스위스 “그라피스포스터 연감”에 화장품광고 포스터 수록(태평양화학)

1977 동아일보 광고대상 최우수상(녹십자 기업 PR광고)

0000 스위스 “그라피스포스터 연감”에 화장품광고 포스터 수록(태평양화학)

1985 사진라이브러리 “포토뱅크”창업

1990 동아일보사 주최 국제사진전 심사위원장

1991 대한민국사진전 심사위원장

0000 한국사진작가협회 자문위원

0000 한국광고사진가협회 고문

1999 올해의 문화인상 수상

0000 별세

개인전

1986 ‘아름다운 우리강산’ 디자인포장센터 / 서울, 한국

1988 ‘우리강산’ L.A 한국문화원초청전 / L.A, 미국

1999 “MESTER”(마에스트로) 헝가리 사진박물관초대전 MAI MANO

(Hungarian House of Photography)/ 부다페스트, 헝가리

그룹전

2006 ‘Korean New Days’ 슬로바키아사진축제 / 브라티슬라바, 슬로바키아

2008 ‘동강사진축제’ 동강사진 박물관 소장전 / 동강, 강원도

2008 ‘현대사진60년전’ 한국현대미술관 / 서울, 한국

2008 ‘한강르네상스전’ 한강시민사업본부 / 서울, 한국

2008 ‘숨겨진 4인전’ 대구사진비엔날레 / 대구, 한국

2009 ‘광화문’ 서울역사박물관 / 서울, 한국

2009 ‘한강르네상스’ 한강시민사업본부 / 서울, 한국

2012 ‘삶의 궤적’ 코리아 소사이어티 / 뉴욕, 미국

2014 ‘디스커버리어워드’, 아를포토페스티벌 / 아를, 프랑스

2014 ‘VIP 1950~60: 빈티지 사진’, 서울시립미술관 북서울 미술관 / 서울, 한국

2015 ‘LA NUIT DE LA PHOTO(사진의 밤)’ / 라쇼드퐁, 스위스

작품집

1986 “우리강산” / 열화당

1987 “삶” / 신태양사

1990 “내가자란 서울” (글.어효선 사진.한영수) / 대원사

2014 “서울모던타임즈” / 한스그라픽

컬렉션

헝가리 사진박물관

서울시립미술관

동강사진박물관

서울역사박물관

Han Youngsoo

1933 Born in Gaeseong, Gyeonggi Province in korea

1958 Joins “Shinsunwhue”(The New Line Group), Korea’s first ever photographic forum

0000 Joins the Photo Artist Society of Korea

0000 Appointed Director of the Photo Artist Society of Korea

0000 [Prophecy] published in Japan’s World Photo Almanac

1959 Elected Vice Chairman of the Photo Artist Society of Korea

0000 Committee member of The Federation of Art & Cultural Organizations of Korea

0000 Joins the Korean Artists Association

1960 [The Maiden] published in Japan’s World Photo Almanac

1961 [Girl in the Alley] published in the World Photo Yearbook

1962 Chief Representative to the Creative Photo Artist Society of Korea

0000 Founding member of the Commercial Photographer’s Association of Korea

1966 Founds Han Youngsoo Photo Forum (Advertising Photo Studio)

1968 Awarded grand prize on the 5th Chosunilbo Advertising Photo Contest

0000 Awarded grand prize on the 5th Chungangilbo Advertising Photo Contest

1970 Master’s Degree in Business Administration, Yonsei University

1973 Advertisement commissioned by Samsung Electronics published in Photographis

1975 Advertisment commissioned by Amorepacific Corporation published in Graphis Poster Annual

1977 Advertisement for the Green Cross Corporation wins the Donga Grand Prize

0000 Advertisment commissioned by Amorepacific Corporation published in Graphis

1985 Launches [Photo Bank], a photography library

1990 Chairman of the awards committee, 25th Dongailbo International Photo Contest

1991 Chairman of the awards committee, 10th Korea Photo Contest

0000 Adviser to the Photo Artist Society of Korea

0000 Adviser to the Commercial Photographer’s Association of Korea

1999 Voted Cultural Figure of the Year

1999 Dies in Seoul on 9. January

SOLO EXHIBITION

1986 [The Nature of Korea], Korea Design & Packaging Center / Seoul, Korea

1988 [The Nature of Korea], Korean Cultural Center / LA, U.S.A

1999 [MESTER] MAI MANO(Hungarian House of Photography) / Budapest, Hungary

GROUP EXHIBITION

2006 [Korean New Days], FOTOFO / Bratislava, Slovakia

2008 [Collection Exhibition], Dongang Museum of Photography / Yeongwol, Korea

2008 [Contemporary Korean Photographs, 1948-2008], National Museum of Modern

0000 and Contemporary Art / Gwacheon, Korea

2008 [Han River Renaissance], City Hall / Seoul, Korea

2008 [ 4 Hidden Photographers], Daegu Photo Biennale / Daegu, Korea

2009 [Gwanghwamoon], Seoul Museum of History / Seoul, Korea

2009 [Han River], Jabeolrae / Seoul, Korea

2012 [Trace of Life], Korea Society / New York, U.S.A

2014 [Discovery Awads], Les Rencontres d’Arles / Arles. Fance

2014 ‘VIP 1950~60: Vintage In Photography’, Seoul Museum of Art / Seoul, Korea

2015 ‘LA NUIT DE LA PHOTO’ / La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland

BOOKS

1986 “The Nature of Korea”

1987 “Life”

1990 “Seoul, Where I Grow Up”

2014 “Seoul, Modern Times”

COLLECTIONS

MAI MANO / Hungarian House of Photography

Seoul Metropolitan Museum

Dong Gang Museum of Photography

Seoul Museum of History

1933 Born in Gaeseong, Gyeonggi Province in korea

1958 Joins “Shinsunwhue”(The New Line Group), Korea’s first ever photographic forum

0000 Joins the Photo Artist Society of Korea

0000 Appointed Director of the Photo Artist Society of Korea

0000 [Prophecy] published in Japan’s World Photo Almanac

1959 Elected Vice Chairman of the Photo Artist Society of Korea

0000 Committee member of The Federation of Art & Cultural Organizations of Korea

0000 Joins the Korean Artists Association

1960 [The Maiden] published in Japan’s World Photo Almanac

1961 [Girl in the Alley] published in the World Photo Yearbook

1962 Chief Representative to the Creative Photo Artist Society of Korea

0000 Founding member of the Commercial Photographer’s Association of Korea

1966 Founds Han Youngsoo Photo Forum (Advertising Photo Studio)

1968 Awarded grand prize on the 5th Chosunilbo Advertising Photo Contest

0000 Awarded grand prize on the 5th Chungangilbo Advertising Photo Contest

1970 Master’s Degree in Business Administration, Yonsei University

1973 Advertisement commissioned by Samsung Electronics published in Photographis

1975 Advertisment commissioned by Amorepacific Corporation published in Graphis Poster Annual

1977 Advertisement for the Green Cross Corporation wins the Donga Grand Prize

0000 Advertisment commissioned by Amorepacific Corporation published in Graphis

1985 Launches [Photo Bank], a photography library

1990 Chairman of the awards committee, 25th Dongailbo International Photo Contest

1991 Chairman of the awards committee, 10th Korea Photo Contest

0000 Adviser to the Photo Artist Society of Korea

0000 Adviser to the Commercial Photographer’s Association of Korea

1999 Voted Cultural Figure of the Year

1999 Dies in Seoul on 9. January

SOLO EXHIBITION

1986 [The Nature of Korea], Korea Design & Packaging Center / Seoul, Korea

1988 [The Nature of Korea], Korean Cultural Center / LA, U.S.A

1999 [MESTER] MAI MANO(Hungarian House of Photography) / Budapest, Hungary

GROUP EXHIBITION

2006 [Korean New Days], FOTOFO / Bratislava, Slovakia

2008 [Collection Exhibition], Dongang Museum of Photography / Yeongwol, Korea

2008 [Contemporary Korean Photographs, 1948-2008], National Museum of Modern

0000 and Contemporary Art / Gwacheon, Korea

2008 [Han River Renaissance], City Hall / Seoul, Korea

2008 [ 4 Hidden Photographers], Daegu Photo Biennale / Daegu, Korea

2009 [Gwanghwamoon], Seoul Museum of History / Seoul, Korea

2009 [Han River], Jabeolrae / Seoul, Korea

2012 [Trace of Life], Korea Society / New York, U.S.A

2014 [Discovery Awads], Les Rencontres d’Arles / Arles. Fance

2014 ‘VIP 1950~60: Vintage In Photography’, Seoul Museum of Art / Seoul, Korea

2015 ‘LA NUIT DE LA PHOTO’ / La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland

BOOKS

1986 “The Nature of Korea”

1987 “Life”

1990 “Seoul, Where I Grow Up”

2014 “Seoul, Modern Times”

COLLECTIONS

MAI MANO / Hungarian House of Photography

Seoul Metropolitan Museum

Dong Gang Museum of Photography

Seoul Museum of History

미군정 3년사 - 빼앗긴 해방과 분단의 서곡 한국근현대사 3

미군정 3년사 - 빼앗긴 해방과 분단의 서곡 한국근현대사 3

한영수 - 서울모던타임즈 Han Youngsoo - Seoul, Modern Times

한영수 - 서울모던타임즈 Han Youngsoo - Seoul, Modern Times