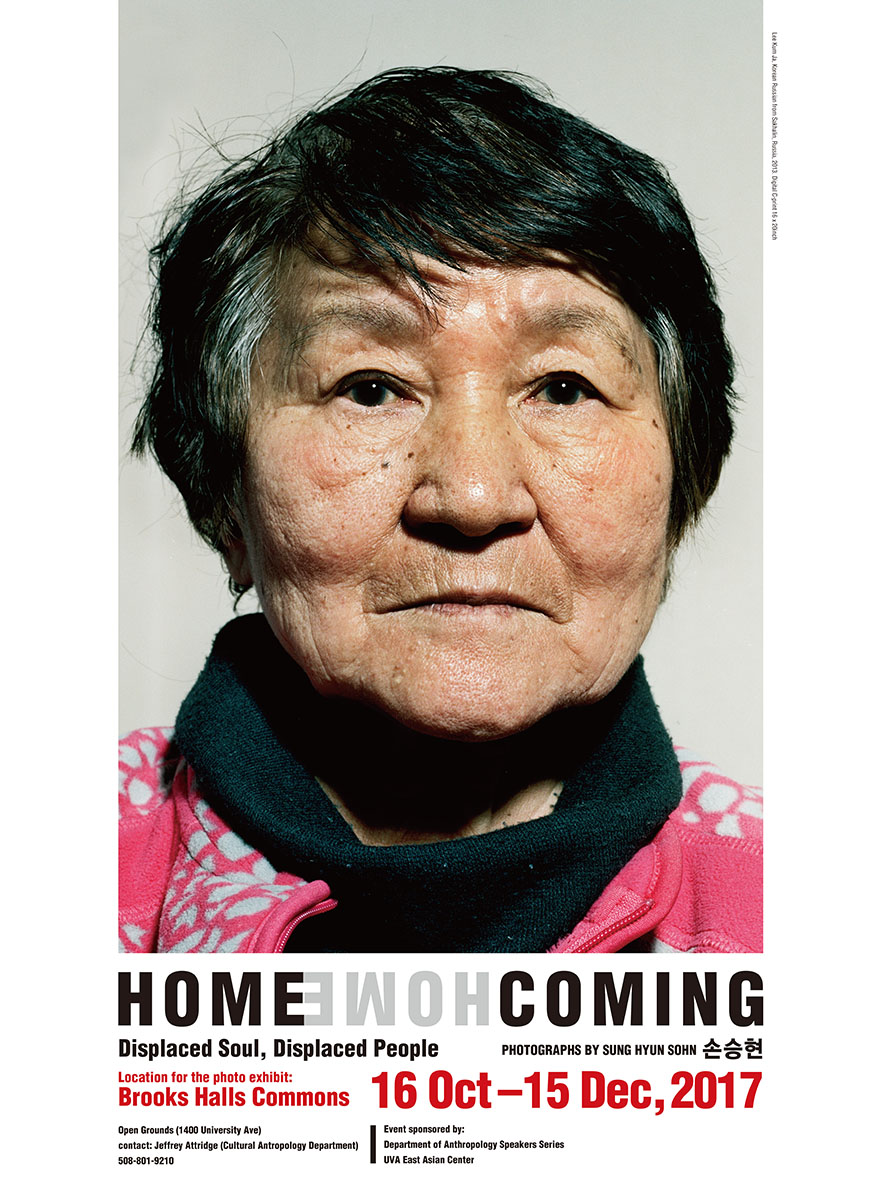

HOMECOMING We are all born into a social context. Some remain in the context that they were born into throughout their lives; others face territories that are unfamiliar to them. The photographs in this exhibition tell the stories of transnational Koreans: those who were born in Korea but later left, those who returned to Korea after spending large parts of their lives in foreign lands, or those who left Korea and were never able to return to their homeland during their lifetime. The ultimate concern of this exhibition is to offer an intimate look at the lives of Korean immigrants in foreign lands and the social institutions that force them to live as strangers, even when they return to Korea. These social institutions and practices, as well as the power structures within societies, influence and alter the human figure, even their most nuanced facial features. The photographs in this exhibition are an archive of historical testimonies of Koreans whose strange fates have led them to live, wandering around the world, in countries such as the USA, Japan, China, and Russia for the past 100 years. Through the lens of appreciation, the intent of this exhibition is to reveal the barren and difficult landscapes of transnational Korean lives.

HOMECOMING

Sung Hyun Sohn

We are all born into a social context. Some remain in the context that they were born into throughout their lives; others face territories that are unfamiliar to them. The photographs in this exhibition tell the stories of transnational Koreans: those who were born in Korea but later left, those who returned to Korea after spending large parts of their lives in foreign lands, or those who left Korea and were never able to return to their homeland during their lifetime. The ultimate concern of this exhibition is to offer an intimate look at the lives of Korean immigrants in foreign lands and the social institutions that force them to live as strangers, even when they return to Korea. These social institutions and practices, as well as the power structures within societies, influence and alter the human figure, even their most nuanced facial features. The photographs in this exhibition are an archive of historical testimonies of Koreans whose strange fates have led them to live, wandering around the world, in countries such as the USA, Japan, China, and Russia for the past 100 years. Through the lens of appreciation, the intent of this exhibition is to reveal the barren and difficult landscapes of transnational Korean lives.

Homecoming is a collection of portraits and stories told by transnational Koreans - from Koreans in Europe and America to Russian Koreans in Sakhalin, from Koryoin Koreans in Central Asia to Chosonjok Koreans in China, and from Saeteomin Koreans (North Korean defectors) to Zainichi Koreans in Japan. Also included are the portraits of repatriated unconverted long-term North Korean prisoners whose lives reflect the grim history of the division of the Korean peninsula. Through the stories that depict what Korean emigrants have had to face in different societies, including that of their own homeland, this exhibition hopes to contribute to the understanding of the diverse cultural stratums that co-exist in Korean society today. Homecoming is composed of five projects recorded over the past twenty years: “Life Histories of Transnational Koreans,” “The Korean Americans,” “70 Year Homecoming,” “House of Unification,” and “Bongwooje Korean Russian Village.”

“Life Histories of Transnational Koreans” is featured on the south left wall. This project is a record of the diverse life histories and personal memories of transnational Koreans, capturing their images both past and present. The end of the Cold War saw the beginning of the age of globalization, a period that, while on the one hand, was accompanied by the increased inter-country movement of capital and labor, on the other hand, saw a weakening of political, economic, and cultural boundaries. Meanwhile, Korea achieved extensive economic growth in an extremely short period of time. As a result, Korea joined the rest of the world in witnessing countless cases of “diaspora” within its borders, accepting immigrant workers and marriage immigrants relocating for political, economic, and historical reasons into Korean society. These immigrants left behind lives in their home countries in order to create new lives in Korea. Among those who have relocated to Korea are Koreans who were moved to Sakhalin, China, and North Korea due to the Japanese occupation and the Korean War, and as a result have experiences of migration and separation in their family histories. Although they share common Korean sentiments, they still find it very difficult to re-acclimate to Korean society due to culture shock, after having absorbed the foreign culture of the countries that they lived over a long period of time, and due to the cold treatment and discrimination they face from Korean society. Fellow Koreans from Sakhalin in Russia, Central Asia, China, Japan, and America, as well as North Korean defectors, live as legal citizens of Korean society; yet, they are seen as minorities in Korea due to political events in Korean history, such as the Cold War and the separation of the peninsula.

“The Korean Americans” is featured on the left right wall. This project, consisting of photographs taken from 2002-2016, is a photographic record of approximately fifty Korean Americans living in North and South America. The Korean American story goes back to 1903 when hundreds of Koreans set sail from Incheon port for a better life in Hawaii as advertised. What they found in Hawaii, however, was a life that was harder than that of their homeland. Present members of Korean-American communities are the descendants of these Korean immigrants, removed by three to four generations. The early generations of Korean Americans spread out across the continent, moving to both the West and East coasts of America to form a community of approximately 2 million today. It is no longer surprising to find Korean Americans working in every field in American industries. Having interviewed Korean Americans since 2002, I’ve found that there is more to their lives than meets the eye. Their life stories and family histories resemble the contradictions also found in the development of contemporary Korean society.

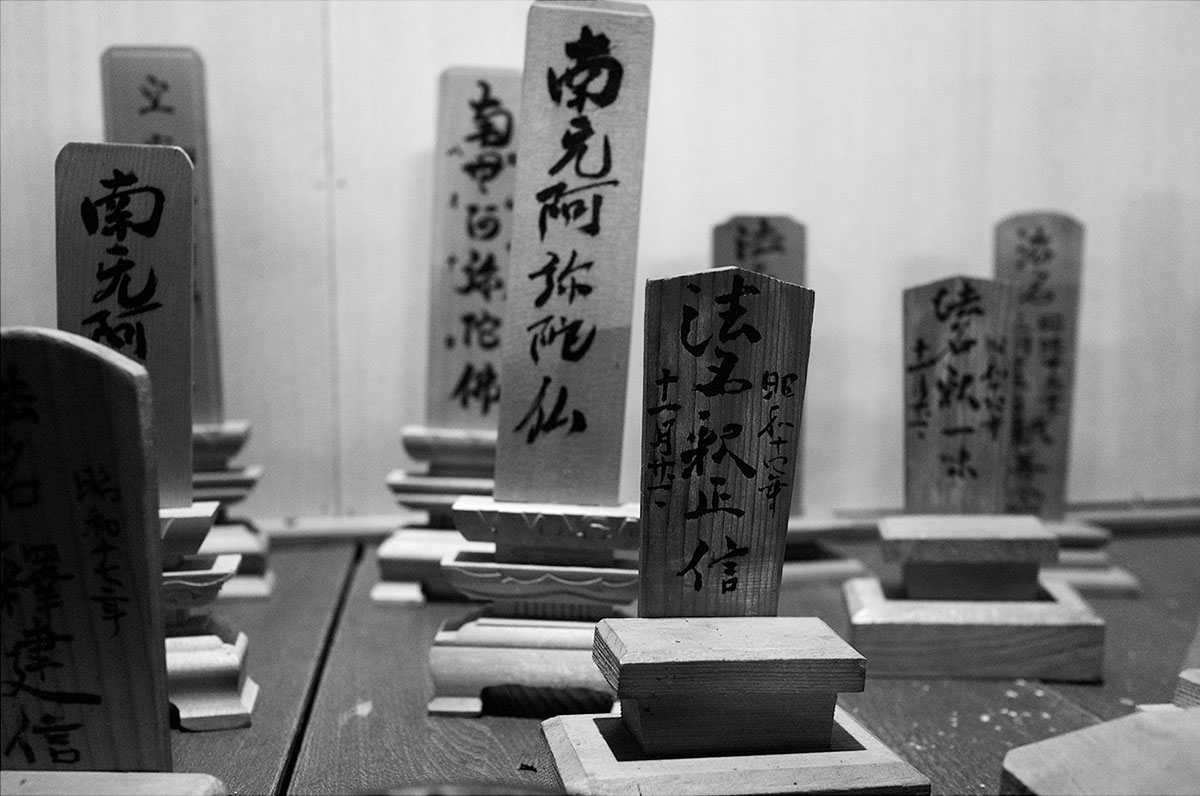

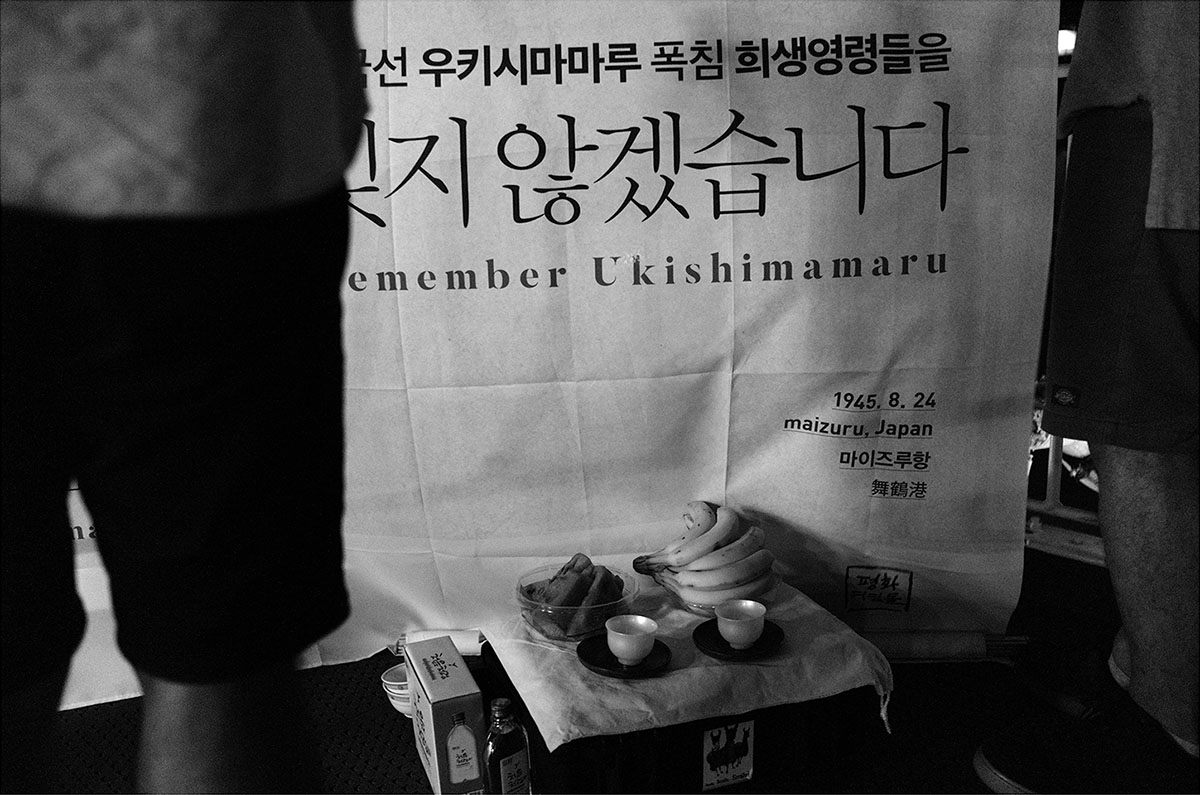

“70 Year Homecoming” is featured on the left side of the west wall. This project is the story of the lives of Zainichi Koreans who were forced to live in Japan during and after the Japanese colonial era and the division of North and South Korea. Between the years of 1939 and 1945, during the Asia-Pacific war, as many as one million Koreans were conscripted to Japan as forced laborers. Within the Korean peninsula, up to four and a half million Koreans were conscripted and forced to serve Japan in the war. Including Koreans that were conscripted domestically, up to six million Koreans were forced to work for the Japanese government or Japanese companies. Along with the issues of forced labor and forced emigration, these photos tell the stories of the Zainichi Koreans who were left in Osaka, Kyoto, and other parts of Japan after the war ended, as well as the problems they faced there, fighting for their right to reside and right to live. The excavation of Korean forced laborers in Hokkaido has been underway since the 1980s, led by citizens and religious leaders in Japan. Since then, and over the past seventeen years since 1997, Korean and Japanese experts, students, and youths have excavated the skeletons of 50 victims who died due to forced labor in Hokkaido during the Asia-Pacific War, along with the remains of about 100 additional victims recovered at temples nearby. While preparing for “70 Year Homecoming,” a project to transport the ashes of 115 Korean victims the long distance back to their homes, this exhibition was planned to illuminate how these victims are connected to people still alive today. After the Pacific War ended, it was well known that there were many bodies of Korean victims in Hokkaido, where they had been brought for forced labor. Their remains were left on the strange island for over 60 years. Forced labor was encouraged by the Japanese government during the war to implement the country’s war policies. Following government mandates, many Japanese companies dragged countless Korean people from their hometowns, forcing them to work until their deaths. While the Japanese government and the perpetrating companies continued to eevade responsibility for what they had done, Korean and Japanese citizens uncovered this historical tragedy and began the work of excavating the remains of Korean victims in order to send their remains home. The excavation project should not be understood merely in terms of the conflict between the assailants and their victims. Rather, this project highlights how this discontinued relationship in history can only be repaired when all those involved in the excavation project dedicate themselves to their duties. “70 Year Homecoming” shows how Korean and Japanese citizens have opened their minds and communicated throughout the cooperative project for the excavation of Korean victims, overcoming any conflicts that exist between the two countries.

“House of Unification” is featured on the west right wall. The term "unconverted long-term prisoner" is in and of itself an ambiguous term coined to label a variety of persons: 1. those who were imprisoned for partisan activities from the Independence of Korea (1945) up to the end of Korean War (1953), 2. active spies from North Korea in the early 70s, 3. victims of fabricated spy cases created by the Department of National Security and facilitated by anti-Communist sentiments spreading among Korean citizens, and lastly 4. those implicated in the cases of Unification Revolutionary Party, The People's Revolutionary Party, and South Korea National Front. Unconverted long-term prisoners are prisoners who refused to sign statements renouncing their beliefs and promising to convert to ideology compatible with that of South Korea. Most of these prisoners who were sentenced to life were eventually released on parole; however, unconverted long-term prisoners who unwaveringly adhered to their ideology were kept in solitary confinement for up to 30 to 45 years. 63 of these prisoners were repatriated to North Korea in September of 2000 under an agreement by the governments of South and North Korea.

“Bongwooje Korean Russian Village” is featured on the north wall. This project depicts Koryoins, or Korean emigrants in Central Asia, who returned to Korea and created a community farm collective. Their story begins with the forced relocation of Koryoins. In July 1937, at the start of the Sino-Japanese War, China and the Soviet Union signed the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact. On the same day, the resolution regarding the deportation of Koryoin was also adopted. The official reason for the forced relocation of Koryoin was to suppress the possibility of Japanese spies infiltrating the areas where Koryoins resided. 171,781 people were forcibly moved over 6,000km from the border regions where they had been living, to the semi-desert regions of Central Asia, and left to resettle in the wintery fields of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. After the first wave of deportation was carried out, Koryoins continued to be deported from different areas of the Soviet Union to various multiethnic regions of Central Asia. After the forced relocation of 1937 and since the Khrushchev era beginning in 1957, Koryoin have been returning to the border regions of Russia, Ukraine, or Chechen. Furthermore, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, many have begun returning to Korea as migrant workers. Although Koryoin have migrated to areas throughout Asia, such as present-day Russia, Central Asia, and Korea, the collective memory that has forged their consciousness is the forced relocation of 1937. The multiethnic cultural experiences they had from working on multicultural collective farms and living within multicultural societies after they were deported, as well as their experiences living in a socialist society, have become the basis of their communal living within the capitalist countries to which they have migrated. Through cultural exchange and marriage, etc. between Koryoin and Jewish, Chechen, Ukrainian, Kurdish, and Russian people, Koryoin have become neighbors and family members in their new homes, creating a new cultural space. For the many Koryoin descendants who have migrated and now live in the Wongok-dong neighborhood of Ansan, South Korea, living in a multicultural community is something that they have already experienced in the countries they previously lived. For Koryoin who have migrated to South Korea and are in the process of creating their community, the experience of living amidst such multiculturalism is already a basis of their consciousness.

For the past twenty years, I have listened to the stories of hundreds of members of the Korean diaspora, those who had to leave behind their homelands and barely managed to live and survive in foreign lands. Each and every one of their stories left a deep impression on my heart. As a photographer, my work has been an attempt to answer questions such as what it means to be human and the motivations of our existence. The answers that I heard in the course of listening to the amazing life histories of my subjects exceeded my expectations by leaps and bounds, often bringing me to tears and giving me a valuable education. Although at first glance, the subjects of this project would be considered weak and vulnerable by most of society, I grew to have a sense of awe and respect for them after hearing their life stories. What my heart responded to most was their exceptional vitality. Their faces were like maps of their lives - lives which had been spent confronting impossibly difficult choices head-on, even when they were faced with such choices every moment of their lives. The goal of this project was to capture and convey in photographs both the visible and invisible parts of their lives.

The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the “state of emergency” in which we live is not the exception but the rule. Walter Benjamin, from “Theses on the Philosophy of History.”

I’d like to thank Professor Byung Ho Chung, Professor David Plath, and Tonohira Yoshihiko. Without their generous support this exhibition wouldn’t have come to fruition.

RECAPTURING A LIGHT LONG LOST

Young Jun Lee

The light has disappeared from their eyes. When they were young, their eyes would’ve sparkled, full of light. But, after having to leave their hometowns behind and settle in new lands, the light has long been lost. The word “hometown” came to mean not a place that you could return whenever you wished, but rather a source of false hope. Dreaming of going home - eyes shining bright with hope - only made it harder, only served to torture them further. And so, they gave up such hope. Who can recapture the light long lost from their eyes? Using the word light to describe someone’s eyes is a metaphor for liveliness. Phrases like “big bright eyes” and “to have stars in one’s eyes” refer to situations where one’s entire face is full of life and energy. That the light has been lost from the eyes of the elderly men and women who were forcefully exiled to Sakhalin means that they have lost their liveliness; the weight on their shoulders, the deep sorrow or ‘han’ of the diaspora, cannot be easily resolved.

Can an old medium that has lost its luster like photography recover the light lost from the eyes of the displaced Sakhalin? Sung Hyun Sohn work is an effort to do just that. Put another way, he is fighting to resolve the ‘han’ of the displaced Sakhalin through photography. Of course, the ‘han’ built up through each and every difficult circumstance and struggle over a long period of time can hardly be resolved with one small camera alone. Rather, the camera is a tool that listens to its subject’s stories. Regarding ‘han,’ some may say that it is a cultural characteristic specific to Korea, but that is, of course, nonsense. Although Korea developed under enormous persecution throughout our history, there are many other peoples who have faced even greater persecution. But ‘han’ is not something that can be measured and compared; it is a temperament, a state of mind. ‘Han’ is a deep sorrow and resentment in one’s heart. When referring to ‘han’ as a culture, based on the dictionary definition for the term, we are referring to the actions and products that give culture its meaning. In other words, if one pounds the ground with rage due to their ‘han,’ that is not culture. ‘Han’ becomes culture through the gestures, songs, drawings, and narratives created in order to release one’s ‘han.’

‘Han’ is not specific to Koreans but it is a way to recollect the deep sorrow and pain of our history. We remember the persecution of our past as sadness. If, however, we remembered our history not as sadness but as a dimension of retaliation, such memories would be felt differently. However, even after being persecuted by Monglia during the Goryeo dynasty and again by Japan in modern history, I have never heard a pledge to retaliate. At most, we cheer fervently for Korea to beat Japan in soccer matches. This may be a result of the ‘han’ we are still carrying with us. Although it can seem overwhelming and inescapable, we are able to eventually untangle and release ourselves from it. That said, although ‘han’ is not something to be taken lightly, it may be unlocked by a single, small key, but searching for that key can lead to years of wandering. Sung Hyun Sohn is finding the key in photographs. Using his camera, Sohn attempts to release the ‘han’ of the Koreans who were conscripted and met their deaths without being able to return to their motherlands, or of those who may have been able to go home in their twilight years, but were unable to take a proper step in their hometowns due to their age and frailty. I would like to introduce one such story, from the website of the Sakhalin Korean Historical Commemoration Society located in Busan [The plea of Sakhalin Koreans] (http://sahallin.net/campaign/hope.php):

“I feel sorry that I write my mother tongue, not as Korean, but as Russian. Please understand. I am from the town of Sinegorsk on the island of Sakhalin. My name is Lee Yong-dae and I was born on February 27, 1950. My parents were brought to Sakhalin by the Japanese government. I am not sure of the exact date, but I believe it was around 1943-1944. My father’s name is Lee Eul-dol and my mother’s name is Cha Mal-yeon. My father worked in the coal mines in Sinegorsk and he passed away in 1951, having never been able to return to his hometown. From my recollection, my mother wept as she sang. Seeing my mother like that made me feel pity for their situation and made me realize what exactly hometown meant. My mother passed away in 1982, also never able to return to her hometown. I have lived the past thirty years like a dog with a collar around its neck due to being stateless. The things I could tell you about living as a stateless person, I could write a book about it.”

Lee Yong-dae, January 29, 2011

Resolving ‘han’ the size of continents using nothing more than a small camera is an impossible task; perhaps it is only possible to grasp the end of its rope. Expecting a camera to play the role of lifesaver is unrealistic. At best, Sohn’s camera is an instrument for recording, a single ear listening to the ‘han’-filled stories of their lives. Truthfully, the value of a photograph is not a matter of whether the image is ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ but rather it is determined by the performative aspect of its meaning and impact in the outside world. In other words, is the image being used as a performance of rescue or ruin, or is it being used to convey information or to stimulate senses, or is it being used for medical purposes or as wartime propaganda? Sohn’s images are used in anthropological practice. In fact, his works are usually exhibited not in art galleries but at anthropology conferences. After all, it would not be right to confine the images of those he has traveled across continents to capture, to the white cubes of art galleries.

The life trajectories of Koreans who have had to leave their motherlands are scratched like a large scar across widely spread geographic regions. From Moscow, Russia to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, reaching as far as Sakhalin, or from China’s Heilong Jiang and Jilin to Beijing, the depth of the wound is continental in scale. Looking at those trajectories from afar, it presents like a map of airline routes. However, the fundamental difference between the life trajectories of diasporic Koreans who were left to settle in unfamiliar lands and airline routes is that the former could not simply cross borders and travel as they pleased. For those who are a part of the diaspora, the term ‘homeland’ is divided into three meanings: the homeland where your ancestors were from, the homeland where you were born, and the homeland where you currently reside as a ‘citizen.’ Such divisions are characteristic of diasporic life. Not only do these three homelands not coincide, the dominant culture or set of values among the three can be extremely different from and incompatible with each another (Seo Gyeong-sik [Tour of the Diaspora: From the Eyes of the Exiled] Dolbaegae 2007, p.114).

Members of the Korean diaspora fall outside of the order of stability sought by the nation-state. The nation-state has little concern for the separated and marginalized that exist on the perimeters of such borders. Thus, it took a long time before those who were conscripted to Sakhalin were able to set foot on Korean soil again. Following the routes of diasporic Koreans around the world, Sohn, along with his camera, has become a member of the diaspora himself. His work has exceeded the parameters of art and now fluctuates somewhere between anthropological study, documentary, and commemoration.

Referring to 70 Years Homecoming, a project comprised of photographs of the vestiges of the lives of those who had been forcibly taken to Japan and who later returned to Korea as ashes, Sohn called it ‘concerned photography.’ In addition, as if carrying out ancestral rites, he humbly retraced and photographed the route taken to return to their hometowns. In order to retrace their steps home, he traveled as far as Hamatonbetzu, the northernmost village of Hokkaido. The remains of many Korean forced laborers had been laid to rest there. Sohn thus participated in their journey to repatriate and return to Korea. The photographic results of this endeavor were not spectacular in the least. Frankly, making the scenes of sorrowful ashes being returned to their homelands into spectacular images is both aesthetically and ethically incongruous. By participating in the process of return, Sohn sought to participate in the suffering of the deceased, as well as in the anguish of those still living. To participate through photography is to participate emotionally. Through ‘concerned photography,’ different from declarative art that allowed no level of contribution from artists in the past, Sohn humbly and devotedly stayed by the side of his subjects. These photographs do not seem to fully belong to the realm of art, but rather, are closer to an anthropological record. Still, this record is vastly different from that of western anthropologists, whose methods were to record and analyze the ‘others’ of South America, Africa, or Asia. Sohn’s work, rather, is an emotional participatory anthropology - studying, in the name of anthropology, those who were forcibly exiled to foreign lands, losing their identities and forced to live in suffering.

Through all of this, was Sohn able to recover the light long lost from their eyes? Realistically, it is asking too much of an individual photographer to do something that even the state couldn’t accomplish. Perhaps Sohn’s camera serves instead as an instrument that testifies that we are living in an era that has lost its light.

In the process of writing this review, I had the opportunity to travel to Irkutsk, a large city in Siberia. At the time, it was early fall so the weather was refreshing and the sun was shining. Birch and pine trees stretched out as far as the eye could see in the seemingly endless Taiga Forest and the air was crisp and clear. But still, Russia is a barren land. Hospitality and language could not be properly conveyed and communicated. It is a place that is likely extremely desolate in the winter. Thinking of our ancestors wandering this land long ago filled my heart with sadness. I was able to go comfortably as a traveler, but they came as displaced people who were left to fend for themselves in Siberia. They would have lost a lot, not just their beloved hometowns, but also their identities and memories. Sohn’s camera is an attempt to recover some of the things that they lost. However, it is not necessary for that attempt to be successful in order for the light to return. The very attempt to capture the enormous ‘han’ using a small camera lens is an act of illumination. Resolving and letting go of the ‘han’ that has built up over so many years is not an easy matter.

I don’t think I am the only one who feels infinitely vulnerable when looking at Sohn’s photographs. It is for this reason that his effort is that much more valuable, since he is attempting to do the nearly impossible. The value of his photographs can only be understood with the passing of time, the full return of those that were taken to other lands, and the true restoration of their identities.

SUNG HYUN SOHN

Walks in Cold Water | Oni Mani Osna Mani

Sung Hyun Sohn was born in Busan in 1971. He studied photography at Joong Ang University(BFA) and fine art photography at the graduate school of the same university(MFA). He received MFA in visual arts from Rutgers University in the U.S. and is currently pursuing his doctoral study in Department of Cultural Anthropology at Hanyang University Graduate School. Sung Hyun Sohn expresses stories on history, society and economy of the Mongoloid race including the Koreans through visual arts. He is currently deep inside the community of native North Americans, together on a journey to their past and present. Every year, he travels around Mongolia and North America, and talks on various topics and criticizes civilization on current issues through photographs and writings. He participated more than 40 times in exhibitions held in New York, Italy and Germany and also the Gwangju Biennale 2002, and was part of multiple publication projects carried out in Korea and other countries. The author wrote 『The Circle Never Ends』(AGIBOOKS, 2007), the story of native Americans, and jointly translated 『Coming to Light』 (Moonji Publishing, 2012), the oral literature of indigenous people. He is the member of Nutopia Forum, a group of New York-based portrait photographers. Now, he is giving lectures on North American culture, geography and cities at a university.

Gaia Arts, Seochogu Bangbaedong 827-3, B1, Seoul, South Korea

www.shsohn.com

Education

2011 - 2015 Doctoral Reserch program, Department of Curtural Anthropology, Hanyang University, South Korea

2003 - 2005 M.F.A Mason Gross School of the Art, Visual Art- Printmaking, Photography, Video Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey , USA

M.F.A Thesis < House of Unification>

1997 - 1999 M.F.A Department of Photography, Fine Art Photography, Joong Ang University, South Korea

M.F.A Thesis < The Age of Devided Land>

1991 – 1997 B.F.A Joong Ang University, Department of Photography, South Korea

Solo Exhibition

2016 Homecoming, University of Illinois, U.S.A

2016 The Art of Memory-70 Year Homecoming, Francisco Hall, Anglican Church of Seoul

2016 70 Year Homecoming, Nishihonganji Temple, Hokkaido, Japan

2015 Life Histories of Transnational Koreans, Korea Foundation Gallery, Seoul

2015 Life Histories of Transnational Koreans, Andong Arts Center, Andong

2015 70 Year Homecoming, Seoul Library, Seoul

2015 Life Histories of Transnational Koreans: Ansan, Hokkaido, Sahalin and Tashkent, Global Lounge Gallery, Hanyang University

2015 70 Year Homecoming, Ichijoji Temple, Hokkaido, Japan

2015 70 Year Homecoming, Francisco Hall, Anglican Church of Seoul

2014 Bright Shadow, Gallery Sagakhyung, Seoul

2013 The Circle Never Ends, Sitting Bull College, ND, USA

2013 Life Histories of Korean Diaspora, Global Lounge Gallery, Hanyang Univ, Ansan, Korea

2012 Life Histories of Korean Diaspora, Platoon Kunsthalle, Seoul

2012 Life Histories of Korean Diaspora, Global Lounge Gallery, Hanyang Univ, Ansan, Korea

2005 Unification House, Mason Gross School of the Art Gallery, New Brunswick, NJ, USA

1999 Shadowy Paradise, Chulwon D.M.Z, Old North Korean Labor Party House, South Korea

1991 Space of Sprit, Chung Ang University Gallery, South Korea

Selected Group Exhibition

2014 Missing Records, Gallery Emu, Seoul

2014 History and Memory, Gwang Ju Metropolitan Museum, Gwang Ju

2013 Missing Records, House of Sharing, Gwang Ju, Kyunggi

2013 The Brain, K-Space, KAIST, Daechun

2013 Era of Portrait, Portrait of Era, Seoul Photography Festival, Seoul Metropolitan Museum

2013 WAR+MEMORY, Junju International Photography Festival, Junju Sori Museum, Junju

2013 Documentary Style, Go-Eun Museum of Photography, Busan

2013 Old Future City, Changwon Asia Contemporary Art Festival, Changwon

2012 Nomadic program – Time & Space, Arko Museum, Seoul, Korea

2012 Incheon Document residency Project, Bupyung Art Center, Bupyung, Korea

2011 Ksana, Xanadu Art Gallery, Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar

2011 Ksana, South Gobi Museum, Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar

2010 Redesigning the East, Wurttembergischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart, Germany

2009 Made in Korea, Hanover, Sinn Leffers, Germany

2009 Hangeul, Bologna, Sala d’Ercole, Palazzo d’Accursio, Italy

2008 Memento Mori, Mokin Gallery

2007 Green Art festival Exhibition, Seoul, Daejon, Busan, Gwangju, Jeunju, South Korea

2005 RCIPP New Print 2004, Mason Gross School of the Art Gallery, New Brunswick, NJ, USA

2004 Unbroken, Denise Bibro Fine Art, New York, USA

2004 Last Summer , Time Square Lobby Gallery, New York, USA

2002 Gwangju Biennale-Project 3; Stay of Execution

2002 Court House, Reconstructed 518 Liberty Park, Gwangju), South Korea

2001 Wind, Wind, Wind, Gwanghwamoon Gallery, Seoul

2001 Seoul, View of Atget, Lux Gallery, Seoul 2002

2001 Design Korea, Seoul Art Center Museum, Seoul

2001 Koan in Seoul is Pyungyang, Gwanghwamoon Gallery, Seoul

2000 Skin, Alternative place Sarubia Dabang, Seoul

2000 Our Photography, Today’s Spirit, Korea Art and Culture Center Gallery, Seoul

2000 Origin of Photography, SK Photo Gallery, Seoul

1999 Photography looks at us, Seoul Metropolitan Museum, Seoul

1999 Memorial Photography, Korea Art and Culture Center Gallery, Seoul,

1999 Memorial Photography, Hanrim Gallery, Daegon

1999 After War, Dong-A Gallery, Daegu

1999 Cinema Sovereign, Culture Independence, Alternative Space Pool, Seoul,

1999 Cinema Sovereign, Culture Independence Liberty Park Gallery, Busan

BOOKS

The Museum of Everyday Life (Vol 1-Vol 7), Eung Chun Kang, Young Mee Kim, Young Chul Kim, Chang Hook Baek, Seung Hyun Sohn, Sagyejeol Publishing, Seoul, 2000-2004

Imagination, Action, Seung Hyun Sohn, Moon Jung Jang, Young Chul Kim, AGI Books, 2007

The Circle Never Ends, Seung Hyun Sohn, AGI Book, 2007

Close Encounters of the Fourth World, Seung Hyun Sohn, Geo Book, 2012

Bright Shadow, Seung Hyun Sohn, April Snow, 2013

Collection

2002 5.18 Foundation, Gwangju, South Korea

2013 Sitting Bull College, ND, USA

Awards

2012 Outstanding Publication Award 2012, Korea Publication Ethics Commission

2003 Rutgers Graduate Scholarship, Mason Gross School of the Arts, USA

2002 Winner, Hankook Baek Sang Publishing Culture Grand Prix

2001 Joong Ang Daily Newspaper’s “ Books of Year 2001” Selection

1993,95,97 Academic Scholarship, Joong Ang University

1996 Gold Prize in Photography, National Collegiate Fine Art Exhibition, Korea

Grants

2015 Exhibition grant, Global Multicultural Institute

2015 Exhibition grant, Seoul City Library

2015 Exhibition grant, Andong Arts Center

2015 Exhibition grant, Korea Foundation

2013 Exhibition grant, Seoul Art Foundation

2012 Publication grant, Korea Publication Ethics Commission

2011 Nomadic Report 2012 Mongolia, Korea Art Council

Press coverage

Hankook Daily covering Life Histories of Transnational Koreans (solo photography exhibition), 2015

YTN, Arirang TV, Hokkaido Daily, Kyunghyang Daily, Asia News, Newsis covering 70 Year Homecoming (solo photography exhibition), 2015

Photonet Magazine article “Cruelty of Civilization” (photography works review), 2011

Kyunghyang Daily covering Close Encounters of the Fourth World (book review), 2012

Kookmin Daily covering Close Encounters of the Fourth World (book review), 2012

KBS “TV Talks on Books” program, The Circle Never Ends (book review), 2007

Hangyerye Newspaper covering The Circle Never Ends (book review), 2007

Shindonga Journal covering The Circle Never Ends (book review), 2007

Monthly Photography Magazine article (photography works review), 2006

Invited Lectures

2015 Close Encounters of the Fourth World, Han Yang University

2015 Contemporary Art Photography, Jongno Women Center

2014 Close Encounters of the Fourth World, Duck Sung Women’s University

2014 Close Encounters of the Fourth World, Kyung Hee Cyber University, Department of American Studies

2014 The Circle Never End, Kook Min University

2014 Contemporary Art Photography, Jongno Women Center

2014 Bright Shadow, Gallery Sagakhyung

2013 Time Diver, Thinking Now, Asian Arts Theatre Vision Design Forum

2013 Bright Shadow, Young Nam University

2012 Close Encounters of the Fourth World, Seoul National University

2012 Close Encounters of the Fourth World, Seogang University

2011 Close Encounters of the Fourth World, Humanitas College, Kyung Hee University

2011 Your Text, Gallery 27, K-SAD

2009 The Circle Never End, Duck Sung Women’s University

2008 The Circle Never End, Kyung Hee Cyber University, Department of American Studies

2007 The Circle Never End, The American Studies Association of Korea, Seoul, Korea

2007 Portfolio Presentation, Santa Fe Workshops, New Mexico, USA

2007 International Artist Residency Program The Society of Korean Photography, South Korea

2006 Artist Conversation Monthly Photographic Art Magazine “New Photographer”

2006 Visiting Artist Chung Ang University, Korea

2005 Insider/outsider - Four Contemporary Korean Photographers at Parsons School of Design, NYC, USA

2002 Artist Talk, Stay of Execution, at May 18 Liberty Park, Gwangju, South Korea

2001 Visiting Artist, Kyungggi University, Korea

2000 Visiting Artist, Kyunghee University, Korea

1999 Pinhole Photography, Sookmyung Women’s University, Korea