에이트리갤러리는 최우영 작가의 개인전 <잊혀진 이웃>展을 오는 11월 19일부터 29일까지 개최한다.

이번 전시는 전국 각지에서 11월 한달간 개최되는 <제1회 한국 다큐멘터리 사진의 달> 전시의 일환으로 다큐멘터리 사진가들과 갤러리가 연대하여 다양한 방식으로 관객과 소통하는 열린 축제이다.

최우영은 2010년 홍익대학교 산업미술대학원 사진디자인 전공 졸업하고 2010년 가나아트스페이스와 부산의 문화매개공간 쌈에서 첫 개인전 ‘잊혀진 이웃’을 가지고 현재도 사람이 살아가는 공간과 환경에 관하여 작업을 이어가고 있다.

작가는 서울에서 진행되었고 현재도 진행중인 뉴타운 개발사업을 통하여 자본과 물질중심의 가치가 도시라는 공간속에서 어떻게 인간을 소외시켜 가는지에 대한 의문을 가지고 본 사진작업을 진행하였다.

작가는 황량한 빈집들의 모습에서 결국 망각의 문제를 환기시킨다. 삶의 터전을 잃고 제 집에서마저 쫓겨나 방랑하며 떠돌아 다닐 수 밖에 없는 도시민들이 많아지는 상황과 더불어 타인의 고통에 대해 점차 우리 스스로 둔감해져가는 현실에 대해 질문을 던진다.

이미 떠나가 버린 도시민들의 흔적들을 기록하며 작가는 부재의 기호들을 통하여 개발이라는 담론속에 가려져 있는 인권에 대한 원론적 질문과 자본주의 사회가 만들어 낸 공허한 허상에 대한 이야기를 하고자 하였다.

자세한 문의는 홈페이지(www.a-tree.org)나 에이트리갤러리(02-3447-3477)로 하면 된다.

이번 전시는 전국 각지에서 11월 한달간 개최되는 <제1회 한국 다큐멘터리 사진의 달> 전시의 일환으로 다큐멘터리 사진가들과 갤러리가 연대하여 다양한 방식으로 관객과 소통하는 열린 축제이다.

최우영은 2010년 홍익대학교 산업미술대학원 사진디자인 전공 졸업하고 2010년 가나아트스페이스와 부산의 문화매개공간 쌈에서 첫 개인전 ‘잊혀진 이웃’을 가지고 현재도 사람이 살아가는 공간과 환경에 관하여 작업을 이어가고 있다.

작가는 서울에서 진행되었고 현재도 진행중인 뉴타운 개발사업을 통하여 자본과 물질중심의 가치가 도시라는 공간속에서 어떻게 인간을 소외시켜 가는지에 대한 의문을 가지고 본 사진작업을 진행하였다.

작가는 황량한 빈집들의 모습에서 결국 망각의 문제를 환기시킨다. 삶의 터전을 잃고 제 집에서마저 쫓겨나 방랑하며 떠돌아 다닐 수 밖에 없는 도시민들이 많아지는 상황과 더불어 타인의 고통에 대해 점차 우리 스스로 둔감해져가는 현실에 대해 질문을 던진다.

이미 떠나가 버린 도시민들의 흔적들을 기록하며 작가는 부재의 기호들을 통하여 개발이라는 담론속에 가려져 있는 인권에 대한 원론적 질문과 자본주의 사회가 만들어 낸 공허한 허상에 대한 이야기를 하고자 하였다.

자세한 문의는 홈페이지(www.a-tree.org)나 에이트리갤러리(02-3447-3477)로 하면 된다.

The Forgotten Neighbors 잊혀진 이웃

서울이라 불리우는 도시공간은 수많은 유, 무기체들이 군집되어 이루어진 거대한 공동체 공간이다. 이 속을 들여다보면 이 거대공간을 구성하고 있는 구성요소들은 마치 생명체의 세포조직들처럼 수없이 생성과 소멸을 반복하며 서울이라는 도시의 생명을 이어가고 있다.

도시는 수축과 팽창을 거듭하며 끊임없이 변모해가고 있으며 그 속에서 사람들의 안식처로 집이라 불리우던 이 장소들은 이제 더 이상 편안한 휴식적 공간으로서의 역할을 하지 않는다. 개발이라는 이름으로 사라져버리게 될 시멘트로 둘러싸인 버려진 공간으로 변해버린 것이다. 그것은 곧 소위 ‘뉴타운’이라는 분홍빛 청사진 뒤에 드리워진 현대사회의 그림자이자 트라우마의 흔적들을 암묵적으로 내포하고 있기도 하다.

곧 사라져버릴 이 공간들을 통해 존재에 대한 기억과 시간의 흔적들을 만나게 된다. 마치 오래된 사찰터에 퇴적물처럼 쌓여있는 족적들처럼 이곳에 숨쉬며 살아가던 이들이 떠나버린 빈 공간들에 흩어져 있는 존재의 체취들은 역설적으로 시간의 기억속에 망각된 순간들을 다시 수면위로 떠오르게 한다.

인간의 생명은 영원하지 않다. 그렇기에 인간은 자신의 유한함을 보완하고픈 욕망을 본능적으로 가지고 있다. 하지만 그들의 욕망으로 만들어지는 소산물들 또한 그 생명은 유한할 수 밖에 없다. 지금은 사람들의 논리에 의해 만들어져 다시 그들의 논리에 의해 사라져 버려야 할 이 공간들은 물질문명속에 사라져 가는 인간의 흔적들이다. 그 공간들은 또 다른 가치존재로 변해가고 사람들은 각자의 상처와 기억들을 새로운 공간과 기능을 통해 지워나가려 한다.

이러한 변화과정은 자연의 섭리로 대변되는 생명의 탄생과 죽음이 아닌, 인위적 해체와 생성으로 인해 수반되는 상처들이다. 이러한 인위적 행위가 반복되고 있는 서울이라는 도시공간 구석구석에 생겨나고 있는 흉터자국들을 이 공간의 구성체들인 우리는 인지하고 있는 동시에 곧 망각해버리고 만다. 순간 순간 생성되는 흉터와 상처를 바라보면서도 어느새 트라우마의 연속성속에서 이미 익숙해져버린 것이 아닐까. 인간의 욕망이라는 가치를 채우기 위해 오히려 인간의 존엄성이라는 가치를 잃어버린 것은 아닐까. 빠르게 급변하는 도시의 변화속도는 이 도시 구성원들에게 무한한 경쟁을 강요하고 있으며 소위 개발과 발전이 아닌 또 다른 시각으로 볼때 깊고깊은 망각의 바다로 우리를 인도하고 있는지도 모른다.

본 작업에 등장하는 장소들 속에 이미 사람의 온기는 사라져 버렸지만 시간의 흔적과 기억들은 여전히 부재속의 존재를 상기시키게 한다. 존재(存在)라는 것은 인지되는 실재(實在)만이 아닌 보이지 않는 부재(不在)를 포함하고 있다. 사라진 존재의 흔적 또한 그림자로 계속 남겨져 있기 때문이다. 방안가득 남아있는 마지막 폐허의 기호들은 이 곳에 살고 있었을 이들의 모습을 마지막으로 증명해주고 있다.

이곳의 풍경은 그러한 연유로 인해 현실속에 존재하면서도 존재하는 곳이 아닌 애매모호한 공간이 되어버렸다. 창문너머로 보이는 현실과의 대조를 통해 본인이 바라본 이 공간들은 서울이라는 공간속에 포함되어 있으면서도 또한 실제로는 그렇지 않은 기이한 공간이다. 바깥세계와는 격리되어 버린 고립된 공간인 것이다.

서울이라는 한국의 수도를 중심으로 진행한 본 작업은 소위 뉴타운 개발이 진행되는 공간들을 위주로 진행하였다. 하루가 다르게 변해가는 한국사회에서 여전히 꺼지지 않는 개발과 건설에 대한 담론, 부동산을 통해 자신들의 물질적 가치를 채우고자 하는 인간들의 끝없는 욕망에 대해 모두가 잊고 외면해가는 현실을 떠올려 보고자 하였다. 많은 이들이 돌아보지 않는 도시의 그림자들에 대해, 삶과 죽음이 교차되는 약육강식 논리와도 같은 생명의 유기체적인 속성을 이야기하고자 하였다.

어느 외국도시에서도 찾아볼 수 없는 동시다발적인 뉴타운 개발현장, 도시 전체가 공사장인 서울. 도시개발의 청사진과 앞으로의 경제적 수익을 자랑하는 그들에게 누군가 갑자기 뜬금없는 질문을 던진다. 이곳에 살아가던 이들은 모두 어디로 떠나버렸는지, 그리고 지금 그들은 행복한 것인지. 우리는 이 그림자들을 밟고 있다. 누구도 그들에게 관심을 기울이지 않는다.

서울은 너무나도 빠르게 변해가고 있다.

집이라는 공간들마저 점점 더 빠르게 변해가는 가속도속에서 재개발이라는 이름속에 그 기억들을 지워나가고 있다. 얼마전 바로 주위에 살아가던 이웃들은 어느새 사라져버렸고 그들을 기억하는 것은 남아있는 마지막 흔적들을 통해서만 얼핏 찾아볼 수 있을 뿐이다. 이 마저도 곧 변화해가는 망각의 바다속으로 사라져 버릴 것이다. 서울 도심 곳곳에 마치 구멍난 블랙홀처럼 아무도 남지 않은 비현실적 공간들 속에서 애매모호한 도시의 중간지대에 위치하고 있는 본인의 모습을 발견하게 된다.

최우영

서울이라 불리우는 도시공간은 수많은 유, 무기체들이 군집되어 이루어진 거대한 공동체 공간이다. 이 속을 들여다보면 이 거대공간을 구성하고 있는 구성요소들은 마치 생명체의 세포조직들처럼 수없이 생성과 소멸을 반복하며 서울이라는 도시의 생명을 이어가고 있다.

도시는 수축과 팽창을 거듭하며 끊임없이 변모해가고 있으며 그 속에서 사람들의 안식처로 집이라 불리우던 이 장소들은 이제 더 이상 편안한 휴식적 공간으로서의 역할을 하지 않는다. 개발이라는 이름으로 사라져버리게 될 시멘트로 둘러싸인 버려진 공간으로 변해버린 것이다. 그것은 곧 소위 ‘뉴타운’이라는 분홍빛 청사진 뒤에 드리워진 현대사회의 그림자이자 트라우마의 흔적들을 암묵적으로 내포하고 있기도 하다.

곧 사라져버릴 이 공간들을 통해 존재에 대한 기억과 시간의 흔적들을 만나게 된다. 마치 오래된 사찰터에 퇴적물처럼 쌓여있는 족적들처럼 이곳에 숨쉬며 살아가던 이들이 떠나버린 빈 공간들에 흩어져 있는 존재의 체취들은 역설적으로 시간의 기억속에 망각된 순간들을 다시 수면위로 떠오르게 한다.

인간의 생명은 영원하지 않다. 그렇기에 인간은 자신의 유한함을 보완하고픈 욕망을 본능적으로 가지고 있다. 하지만 그들의 욕망으로 만들어지는 소산물들 또한 그 생명은 유한할 수 밖에 없다. 지금은 사람들의 논리에 의해 만들어져 다시 그들의 논리에 의해 사라져 버려야 할 이 공간들은 물질문명속에 사라져 가는 인간의 흔적들이다. 그 공간들은 또 다른 가치존재로 변해가고 사람들은 각자의 상처와 기억들을 새로운 공간과 기능을 통해 지워나가려 한다.

이러한 변화과정은 자연의 섭리로 대변되는 생명의 탄생과 죽음이 아닌, 인위적 해체와 생성으로 인해 수반되는 상처들이다. 이러한 인위적 행위가 반복되고 있는 서울이라는 도시공간 구석구석에 생겨나고 있는 흉터자국들을 이 공간의 구성체들인 우리는 인지하고 있는 동시에 곧 망각해버리고 만다. 순간 순간 생성되는 흉터와 상처를 바라보면서도 어느새 트라우마의 연속성속에서 이미 익숙해져버린 것이 아닐까. 인간의 욕망이라는 가치를 채우기 위해 오히려 인간의 존엄성이라는 가치를 잃어버린 것은 아닐까. 빠르게 급변하는 도시의 변화속도는 이 도시 구성원들에게 무한한 경쟁을 강요하고 있으며 소위 개발과 발전이 아닌 또 다른 시각으로 볼때 깊고깊은 망각의 바다로 우리를 인도하고 있는지도 모른다.

본 작업에 등장하는 장소들 속에 이미 사람의 온기는 사라져 버렸지만 시간의 흔적과 기억들은 여전히 부재속의 존재를 상기시키게 한다. 존재(存在)라는 것은 인지되는 실재(實在)만이 아닌 보이지 않는 부재(不在)를 포함하고 있다. 사라진 존재의 흔적 또한 그림자로 계속 남겨져 있기 때문이다. 방안가득 남아있는 마지막 폐허의 기호들은 이 곳에 살고 있었을 이들의 모습을 마지막으로 증명해주고 있다.

이곳의 풍경은 그러한 연유로 인해 현실속에 존재하면서도 존재하는 곳이 아닌 애매모호한 공간이 되어버렸다. 창문너머로 보이는 현실과의 대조를 통해 본인이 바라본 이 공간들은 서울이라는 공간속에 포함되어 있으면서도 또한 실제로는 그렇지 않은 기이한 공간이다. 바깥세계와는 격리되어 버린 고립된 공간인 것이다.

서울이라는 한국의 수도를 중심으로 진행한 본 작업은 소위 뉴타운 개발이 진행되는 공간들을 위주로 진행하였다. 하루가 다르게 변해가는 한국사회에서 여전히 꺼지지 않는 개발과 건설에 대한 담론, 부동산을 통해 자신들의 물질적 가치를 채우고자 하는 인간들의 끝없는 욕망에 대해 모두가 잊고 외면해가는 현실을 떠올려 보고자 하였다. 많은 이들이 돌아보지 않는 도시의 그림자들에 대해, 삶과 죽음이 교차되는 약육강식 논리와도 같은 생명의 유기체적인 속성을 이야기하고자 하였다.

어느 외국도시에서도 찾아볼 수 없는 동시다발적인 뉴타운 개발현장, 도시 전체가 공사장인 서울. 도시개발의 청사진과 앞으로의 경제적 수익을 자랑하는 그들에게 누군가 갑자기 뜬금없는 질문을 던진다. 이곳에 살아가던 이들은 모두 어디로 떠나버렸는지, 그리고 지금 그들은 행복한 것인지. 우리는 이 그림자들을 밟고 있다. 누구도 그들에게 관심을 기울이지 않는다.

서울은 너무나도 빠르게 변해가고 있다.

집이라는 공간들마저 점점 더 빠르게 변해가는 가속도속에서 재개발이라는 이름속에 그 기억들을 지워나가고 있다. 얼마전 바로 주위에 살아가던 이웃들은 어느새 사라져버렸고 그들을 기억하는 것은 남아있는 마지막 흔적들을 통해서만 얼핏 찾아볼 수 있을 뿐이다. 이 마저도 곧 변화해가는 망각의 바다속으로 사라져 버릴 것이다. 서울 도심 곳곳에 마치 구멍난 블랙홀처럼 아무도 남지 않은 비현실적 공간들 속에서 애매모호한 도시의 중간지대에 위치하고 있는 본인의 모습을 발견하게 된다.

망각과 맞서는 부재의 기호들

‘잊혀진 이웃’ 연작에서 최우영은 서울 도심의 재개발지역에 대한 시각적 탐사를 해나가고 있다. 재개발을 둘러싼 각종 사회문제가 제기되어온 것은 어제 오늘의 일이 아니며, 나아가 여전히 현재진행형으로 최근의 용산 참사에까지 이르고 있다. 도심 지역의 재개발 사업이 단순히 도시미관을 해치는 낡은 시설물들을 해체하여 현재의 도시경관과 조화를 이루도록 개축하는 데 있지만은 않다는 점은 분명하다. 도시란 수축과 팽창을 거듭하면서 꾸준히 변모해나가는 살아 있는 공간이며, 삶의 양태변화에 부합하는 장소로 거듭나야 하는 가변적인 공간이다. 재개발은 그 변화를 끌어내기 위한 최소한의 수단이다. 문제는 부작용을 줄일 수 있는 최선의 방법을 찾아내는 일이다. 개발이 새로운 삶의 환경을 인위적으로 만들어나가는 것이라면, 거기에는 필연적으로 단절이 개입하기 때문이다. 삶을 이전과 이후, 둘로 나누어버리는 단절 앞에서 사람은 어찌할 바를 모른다. 주어진 환경에 적응하여 살다가 갑작스럽게 낯선 환경에 팽개쳐지는 것이다. 더욱이 재개발이 만들어내는 단절의 현실은 한국사회의 특수성과 맞물려 단지 낯선 환경을 만들어내는 데 그치지 않고, 그곳에서 살아가던 사람들을 쫓아내는 결과를 빚어낸다. 작가는 그렇게 쫓겨난 사람들이 살았던 공간의 폐허를 일관된 시각 하에서 담아내고 있다.

개발이 야기한 도시 공간의 변모를 사진으로 기록한 예는 많다. 1850년대에 시작된 근대적 도시계획으로 변모해가는 파리의 모습을 카메라로 담아낸 샤를 마르빌(Charles Marville)이나, 1900년대 파리의 구도시를 기록한 외젠느 앗제(Eugéne Atget)가 그 원형이다. 이 경우들은 구도시의 모습을 자료로 남겨두고자 하는 구체적인 목적을 갖고 있었다. 마르빌은 정부의 의뢰를 받아서, 앗제는 개인적인 차원에서 작업을 진행했다는 차이만 있을 뿐, 사라지기 이전의 도시 모습을 아카이브의 형태로 보존하겠다는 의지가 이 기록의 의미를 결정지었다. 우리의 경우도 관 주도로, 혹은 사진가 개인의 사적인 관심 덕분에 다양한 유형의 도시 기록을 가질수 있었다. 1960 -70년대를 이끌었던 개발 독재의 결과로 빠르게 변해가는 서울의 주거 환경에 대한 사진들이 부분적으로 보존되어 있는 것이다. 이는 다행스런 일이나 만족스러울 만큼은 아니다. 관점도 다양하지 않고 기록의 대상도 부분적이기 때문이다. 최우영의 작업은 2000년대의 서울을 바라보는 흥미로운 시각을 끌어들이고, 관심의 대상과 폭을 넓혀 우리의 도시 기록을 풍요롭게 살찌우고 있다는 점에서 주목할 만하다.

‘잊혀진 이웃’의 일차적 의미가 도시 기록에 있는 것은 맞지만 그것이 딱딱하고 무미건조한 ‘자료’ 생산을 위한 기록에서 멈추는 것은 아니다. 작가가 이 작업에서 시도하고 있는 ‘기록’의 방법론은 정보를 긁어모아 재개발이 야기한 부정성을 알리는 계몽과 설득의 그것만이 아니기 때문이다. 오히려 작가는 사회학적 관심에서 출발하여 이 빈 집들에서 풍겨 나오는 정취를 쓸쓸한 서정주의의 차원으로 끌어올리고 있다. 사람들이 쫓겨난 빈 집에서 서정성을 보는 것은 어떤 점에서 이율배반적일 뿐만 아니라 퇴폐적이기까지 하다. 거기에는 무엇보다도 우선 박탈당한 삶이 은폐되어 있기 때문이다. 재개발이 표방하는 고상한 명분과 소수의 사람들에게만 주어지는 경제적 혜택의 뒤편에는 훨씬 많은 실거주자들의 신음과 추방의 그림자가 드리워져 있는 것이다. 이를 눈치 챌 수 있도록 돕는 잔잔한 형식과 상징의 결이 이 작업의 쓸쓸한 서정주의를 만들어내는 힘이라 할 수 있겠다. 그것이 이 작업을 정교한 메시지의 전달을 위해 강론에 가까워 지는 설득적 이미지와 구분해준다.

우선 눈에 띄는 것은 빈 집들의 전면을 차지하고 있는 창문이다. 작가는 재개발의 전모를 보여주는 잡다한 주변 정황들을 과감히 배제하고 빈 집의 내부, 그것도 거실과 같은 실내 공간을 선택하여 이를 재개발의 정형으로 제시한다. 헐려나간 건물의 일부나 길 주변에 흩어져 있을 법한 돌무더기, 무너진 벽과 같은 재개발의 보편적인 상징들은 보이지 않는다. 대신 실내에 어지럽게 널려 있는 생활소품들과 뜯겨나간 벽지, 무너져 내린 천정, 헐린 벽의 파편 등이 그것을 대신하고 있다. 이 실내공간의 전면에 위치한 창문도 온전하진 않다. 창틀은 심하게 훼손되어 건물 구조로서의 뚫린 벽에 불과한 모습인 것이다. 바깥 공기를 막아주던 유리도 깨져나가 볼품없는 창은 단지 바깥 세계를 향해 열려 있을 뿐이다. 창을 통해 보이는 세계, 그것은 폐허로 변해버린 빈집과 확연히 구분되는 현실공간이다. 지금은 초라하게 무너져 내렸지만 한때는 이곳도 창 너머로 보이는 세계와 크게 다르지 않았다. 아직 채 뜯겨나가지 않은 반투명의 커튼 뒤로 보이는 시가 풍경, 흉측한 몰골만 남은 사각의 틀 너머로 펼쳐진 야산, 외관은 아직 멀쩡해 보이는 이웃 동네의 주택 단지, 그 너머에 우뚝 솟아있는 아파트, 이 모든 것은 잔해만 남은 실내와 확연히 비견되는 모습이다. 요컨대 폐가가 되어버린 이 빈집들도 예전에는 저 온전한 세계에 속해 있었다. 그러나 이제는 창밖으로 보이는 저 세계로 다시 돌아갈 수 없다. 무너져 내린 천정이나 뜯겨나간 벽들과 함께 이 빈집들은 구겨진 세계가 되어버렸다.

한편 완전히 뜯겨나가 사각의 틀만 남아 있는 창은 액자처럼 보이기도 한다. 그 창이 보여주는 바깥 풍경은 캔버스 위에 그려진 그림과도 같다. 잘게 조각난 벽의 파편들이 어지럽게 널려 있는 어수선한 실내에 비해 단정하게 정돈된 창밖의 모습은 상대적으로 얼마나 정갈해 보이는가. 정면에 위치한 창틀이 보여주는 바깥 세계는 한때 이곳에 살았던 쫓겨난 이들의 눈에는 가닿고 싶은 바람으로서의 세계, 요컨대 동경의 대상처럼 보인다. 이 칙칙한 빈집이 암울한 현실이라면 창틀이 보여주는 모습은 집 잃은 자들이 속하지 못한 저 너머의 세계인 셈이다. 그렇게 창틀은 어디론가 떠나버린 이 빈집의 옛 주인들의 암담한 심경에 대한 메타포가 된다.

다음은 바닥에 나뒹굴고 있는 집의 상처와 이주의 흔적들. 빈집들이 철거될 운명에 처해 있음을 알려주는 징표들은 무수히 많다. 천정의 조명등이 뜯겨나간 자국이나 누더기가 되어버린 벽지, 해체된 각종 건축자재들을 한 곳에 쌓아놓은 모습, 배선이 훤히 보일 정도로 무너져 내린 천정, 바닥에 내팽개쳐진 창문, 밟으면 버석거릴 듯이 널려 있는 깨진 유리조각, 이 모든 집의 파편들은 이제 이 빈집의 기능이 사라지고 없음을, 더 이상 집의 구실을 할 수 없음을 여실히 보여주고 있다. 조형적으로 보자면 주의를 분산시키는 잡다한 집의 파편들 때문에 구성이 어지러워질 수 있지만 중앙에 위치한 창문으로 수렴되는 원근법적 구도가 시선을 모아주고 바닥에 널린 잔해들이 덩어리로 뭉쳐 화면을 단순화시키는 효과를 낳는다. 복잡한 화면에 간결한 구조가 생겨나는 것이다. 또한 양 옆에 위치한 깔끔한 벽면에 비해 바닥에 널린 조각들의 무게감은 화면에 안정감을 실어주기도 한다. 이것이 자칫하면 어지럽고 불안정해질 수 있는 폐허의 공간에 안정된 조형성을 부여해준다.

집을 할퀴고 지나간 난폭한 철거의 잔해와 더불어 남아 있는 것은 집을 떠난 이들에게 속해 있던 거주의 흔적들이다. 「유리의 얼굴이 그려진 방 - 이문동」에는 창문 바로 아래 아이들의 눈높이에 맞추어 벽에 붙여놓은 한글 학습용 포스터와 구구단을 비롯한 각종 학습 교재가 보인다. 아이들의 방이었음을 짐작케 하는, 누더기가 되어버린 교재들이다. 「작은 의자가 놓인 거실 - 아현동」의 벽에는 결혼기념 사진으로 보이는 액자가 비스듬히 놓여 있고 중앙에는 뒤집혀 정체를 알 수 없는 또 다른 사진 액자와 훌라후프가 버려져 있다. 얼마나 체념이 깊었으면, 혹은 얼마나 급박했으면 결혼사진도 팽개치고 떠났을까, 아직 온전한 상태인 아이의 장난감마저 버려두고 말이다. 「노란 벽지로 도배된 방 - 남가좌동」에서도 처량한 이주의 흔적은 되풀이된다. 아이가 정성껏 만들었음을 한눈에 알 수 있는 물고기 모양의 모빌은 이 파괴된 방의 어린 여주인을 할퀴고 지나갔을 상심을 암시하고 있다. 「성찬이가 뛰어놀던 거실 - 왕십리동」에서 거실 구석에 놓인 탬버린과 우산, 훌라후프는 아이가 채 거둬가지 못한 자기 집에 대한 미련의 상징처럼 보인다. 「외국인 노동자 부부가 살던 방 - 상왕십리동」에도 삶의 일부였던 것들을 포기하고 떠났음을 알려주는 흔적들이 잘게 부수어진 벽 조각들과 어지럽게 섞여 있다. 가족 앨범을 비롯하여 슬리퍼와 수건, 비디오테이프, 롤러스케이트 한쪽, 심지어는 비와 먼지떨이까지 남겨두고 유랑을 떠난 것이다. 그들은 자신의 과거를 버려야만 했다. 그들이 버릴 수밖에 없었던 것은 그것뿐만이 아니다. 「현숙이가 장구를 치던 방-남가좌동」에 뒹굴고 있는 망가진 장구와 기타, 죽부인등 그들의 삶과 얽혀 있던 모든 크고 작은 물품들이 모조리 주인을 잃고 만 것이다. 그들은 떠나야만 했다. 새로운 보금자리를 찾아 희망을 품고 떠난 것이 아니라 떠밀려서 어쩔 수 없이 쫓겨났다. 재개발의 어두운 그림자가 그렇게 이 빈집들의 내부에 짙게 드리워져 있다.

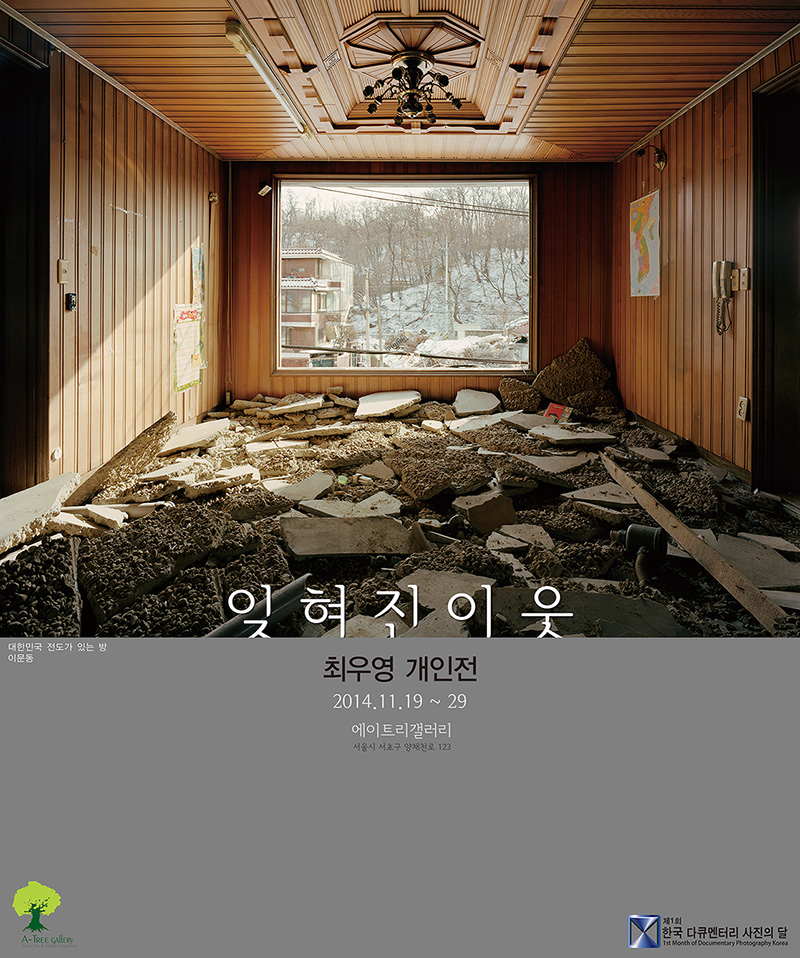

작가가 빈집을 바라보는 시각은 공간을 포착하는 일관된 구도와 앵글, 폐허와 대결하는 정공법을 통해 결정된다. 그 시각이 빚어낸 결과는 폐허를 장관으로 만드는 그로테스크한 조형성과도 유사해 보인다. 파괴된 방에 비장미가 스며드는 것과도 유사하다 하겠다. 그러나 이러한 조형성은 어느새 다시 연극적 재현에서나 찾아볼 수 있는 가장된 현실감을 창출해내기에 이른다. 꾸며낸 현실에서 느낄 수 있는 어색하고 부자연스러운 정조가 개입하는 것이다. 빈집 내부의 모습을 작가가 공들여 재배치했는가, 그렇지 않은가는 중요하지 않다. 문제는 그 모습이 한결같이 집에 대한 일반의 인식을 교란시키는 데 이바지하고 있다는 점이다. 「대한민국 전도가 있는 방 - 이문동」에서 볼 수 있듯 거실 전체를 빼곡히 채운 부서진 건축자재들이 어디에서 왔는지 우리는 알 수 없다. 목재로 둘러싸인 벽면과 천정은 그대로인데 누가, 어디에서 이 파손된 벽 더미를 옮겨왔단 말인가. 그것들은 마치 바닥 전체를 여백 없이 덮기 위해 차곡차곡 쌓아놓은 것처럼 보이기도 한다. 어쨌든 이 파괴된 방들은 모두 주거공간이기를 그치고 공사판으로 둔갑한다. 그것이 이 방들의 현실성이다. 하지만 여전히 빈집 구석구석에 묻어 있는 사람의 자취들은 이 공간의 정체성을 교묘히 비튼다. 공사장이라 할 수도 없고 주거공간이라 할 수도 없는 중간지대, 낯설다 못해 공간의 물리적 현실성마저 부정하려 드는 완강한 인식의 저항이 이 빈집의 기이함을 증폭시켜주는 것이다.

이러한 기이함은 창문 너머 저편으로 보이는 그림같은 현실과의 대조를 통해 한층 강화된다. 그 기이함은 「철창이 있는 방 - 상왕십리동」이 보여주듯 철거될 집과 바깥 세계를 엄격히 구분하는 데서 오는 것이기도 하다. 이 빈 집은 바깥세계로부터 격리되어 있는 것이다. 사람이 더 이상 살지 않는 빈집들은 세상에서 유리되어 통로조차 없는 갇힌 방이 되어버렸다. 서울시내 한복판에 있으면서도 재개발 지역의 빈집들은 마치 육지로부터 고립된 섬처럼 세상에서 떨어져나간 셈이다. 지리적으로, 행정구역상으로는 서울시에 포함되지만 실제로는 그렇지 않은 기이한 지위가 이 지역의 위상을 결정한다. 이곳은 그렇게 서울시에 없는 곳이 된다. 서울에서 지워진 이곳은 그래서 기이해 보인다. ‘잊혀진 이웃’의 작품들에서 가공된 듯한 현실감, 꾸며낸 듯한 현실성이 느껴지는 것도 그런 이유 때문이다. 창 하나를 경계로 확연히 나뉘는 두 세계의 이질감이 그 가공된 현실성을 더욱 증폭시켜주고 있다.

작가는 황량한 빈집들의 모습에서 결국 망각의 문제를 환기시킨다. 주변에 살던 이웃들이 모두 어디론가 떠나버린 이곳, 남아 있는 것은 폐허뿐이지만 그마저도 조만간 사라질 운명이다. 빈집들은 주인에 대한 기억을 아직은 희미하게 보존하고 있다. 그들이 미처 추스르지 못하고 남겨놓은 일상용품이 아니더라도 벽 구석구석에 묻어 있는 삶의 채취들이 그것을 붙들어두고 있는 것이다. 하지만 재개발이 진행되는 과정에서 그마저도 새로 들어설 건물들과 함께 사라질 운명이다. 이웃사람들의 보금자리였던 집들이 철거됨과 동시에 사람 자체도 망각되어 가는 재개발의 현실, 그래서 작가는 작업노트에 “누구도 그들에게 관심을 기울이지 않는다”고 냉소적으로 적는다. 그 망각을 일깨워준 것은 빈집의 공허함이다. 있을 때는 모르다가 없으면 알게 되는 것이 존재감 아니던가. 하여 이 빈집들에서 작가가 받은 트라우마는 무너진 벽이나 떨어져 나간 창틀, 구겨진 벽지, 어지럽게 널려 있는 벽돌조각들에서 오는 것이 아니라 아무도 없음, 요컨대 공허에서 온다. 그 공허가 상처를 주는 까닭은 타인에 대한 망각을 물려줄 터이기 때문이다. 문제는 그래서 삶의 터전을 잃고 제 집에서마저 쫓겨나 고통 받는 타인이 많아지는 상황과 더불어 타인의 고통에 대해 점차 우리 스스로 둔감해져가는 현실이다. 그렇게 무디고 둔탁해져가는 이유는 망각 때문이다. 하여 망각을 걷어내기 위해 작가는 공허를 환기시킨다. 창문 너머에서 들어오는 빛이 빈집 구석구석까지 샅샅이 훑고 지나가지만 아무도 없다. 바깥세상의 빛이 탐지해내는 것은 그들이 남기고 간 흔적과 폐기의 징후로 방안 가득 쌓인 집의 부속품들뿐이다. 그렇게 없음을 환기시킨다고 해서 망각을 이겨낼 수 있을까. 작가는 그 점에 대해 명쾌한 답을 갖고 있지는 않은 듯하다. 다만 망각과 싸우기 위해 빈집 가득 공허를 채워 이를 보여 주려 할 뿐이다. 요컨대 방안 가득 널려 있는 폐허의 기호들은 공허를 환기시켜주기 위한 소품들이라 할 수 있다. 사라진 타인들을 기억에 붙잡아둘 수 있는 수단은 그것뿐이므로, 다시 말해 그들의 부재는 그들이 남겨놓은 흔적을 통해서만 알려질 수 있으므로. 이처럼 작가가 빈집에서 진정으로 목격한 것은 파손된 집의 잔해가 아니라 그들의 부재라 할 수 있다. 그렇게 작가는 부재를 환기시킴으로써 망각과 맞서고 있는 것이다.

글. 박평종(미학, 사진비평)

‘잊혀진 이웃’ 연작에서 최우영은 서울 도심의 재개발지역에 대한 시각적 탐사를 해나가고 있다. 재개발을 둘러싼 각종 사회문제가 제기되어온 것은 어제 오늘의 일이 아니며, 나아가 여전히 현재진행형으로 최근의 용산 참사에까지 이르고 있다. 도심 지역의 재개발 사업이 단순히 도시미관을 해치는 낡은 시설물들을 해체하여 현재의 도시경관과 조화를 이루도록 개축하는 데 있지만은 않다는 점은 분명하다. 도시란 수축과 팽창을 거듭하면서 꾸준히 변모해나가는 살아 있는 공간이며, 삶의 양태변화에 부합하는 장소로 거듭나야 하는 가변적인 공간이다. 재개발은 그 변화를 끌어내기 위한 최소한의 수단이다. 문제는 부작용을 줄일 수 있는 최선의 방법을 찾아내는 일이다. 개발이 새로운 삶의 환경을 인위적으로 만들어나가는 것이라면, 거기에는 필연적으로 단절이 개입하기 때문이다. 삶을 이전과 이후, 둘로 나누어버리는 단절 앞에서 사람은 어찌할 바를 모른다. 주어진 환경에 적응하여 살다가 갑작스럽게 낯선 환경에 팽개쳐지는 것이다. 더욱이 재개발이 만들어내는 단절의 현실은 한국사회의 특수성과 맞물려 단지 낯선 환경을 만들어내는 데 그치지 않고, 그곳에서 살아가던 사람들을 쫓아내는 결과를 빚어낸다. 작가는 그렇게 쫓겨난 사람들이 살았던 공간의 폐허를 일관된 시각 하에서 담아내고 있다.

개발이 야기한 도시 공간의 변모를 사진으로 기록한 예는 많다. 1850년대에 시작된 근대적 도시계획으로 변모해가는 파리의 모습을 카메라로 담아낸 샤를 마르빌(Charles Marville)이나, 1900년대 파리의 구도시를 기록한 외젠느 앗제(Eugéne Atget)가 그 원형이다. 이 경우들은 구도시의 모습을 자료로 남겨두고자 하는 구체적인 목적을 갖고 있었다. 마르빌은 정부의 의뢰를 받아서, 앗제는 개인적인 차원에서 작업을 진행했다는 차이만 있을 뿐, 사라지기 이전의 도시 모습을 아카이브의 형태로 보존하겠다는 의지가 이 기록의 의미를 결정지었다. 우리의 경우도 관 주도로, 혹은 사진가 개인의 사적인 관심 덕분에 다양한 유형의 도시 기록을 가질수 있었다. 1960 -70년대를 이끌었던 개발 독재의 결과로 빠르게 변해가는 서울의 주거 환경에 대한 사진들이 부분적으로 보존되어 있는 것이다. 이는 다행스런 일이나 만족스러울 만큼은 아니다. 관점도 다양하지 않고 기록의 대상도 부분적이기 때문이다. 최우영의 작업은 2000년대의 서울을 바라보는 흥미로운 시각을 끌어들이고, 관심의 대상과 폭을 넓혀 우리의 도시 기록을 풍요롭게 살찌우고 있다는 점에서 주목할 만하다.

‘잊혀진 이웃’의 일차적 의미가 도시 기록에 있는 것은 맞지만 그것이 딱딱하고 무미건조한 ‘자료’ 생산을 위한 기록에서 멈추는 것은 아니다. 작가가 이 작업에서 시도하고 있는 ‘기록’의 방법론은 정보를 긁어모아 재개발이 야기한 부정성을 알리는 계몽과 설득의 그것만이 아니기 때문이다. 오히려 작가는 사회학적 관심에서 출발하여 이 빈 집들에서 풍겨 나오는 정취를 쓸쓸한 서정주의의 차원으로 끌어올리고 있다. 사람들이 쫓겨난 빈 집에서 서정성을 보는 것은 어떤 점에서 이율배반적일 뿐만 아니라 퇴폐적이기까지 하다. 거기에는 무엇보다도 우선 박탈당한 삶이 은폐되어 있기 때문이다. 재개발이 표방하는 고상한 명분과 소수의 사람들에게만 주어지는 경제적 혜택의 뒤편에는 훨씬 많은 실거주자들의 신음과 추방의 그림자가 드리워져 있는 것이다. 이를 눈치 챌 수 있도록 돕는 잔잔한 형식과 상징의 결이 이 작업의 쓸쓸한 서정주의를 만들어내는 힘이라 할 수 있겠다. 그것이 이 작업을 정교한 메시지의 전달을 위해 강론에 가까워 지는 설득적 이미지와 구분해준다.

우선 눈에 띄는 것은 빈 집들의 전면을 차지하고 있는 창문이다. 작가는 재개발의 전모를 보여주는 잡다한 주변 정황들을 과감히 배제하고 빈 집의 내부, 그것도 거실과 같은 실내 공간을 선택하여 이를 재개발의 정형으로 제시한다. 헐려나간 건물의 일부나 길 주변에 흩어져 있을 법한 돌무더기, 무너진 벽과 같은 재개발의 보편적인 상징들은 보이지 않는다. 대신 실내에 어지럽게 널려 있는 생활소품들과 뜯겨나간 벽지, 무너져 내린 천정, 헐린 벽의 파편 등이 그것을 대신하고 있다. 이 실내공간의 전면에 위치한 창문도 온전하진 않다. 창틀은 심하게 훼손되어 건물 구조로서의 뚫린 벽에 불과한 모습인 것이다. 바깥 공기를 막아주던 유리도 깨져나가 볼품없는 창은 단지 바깥 세계를 향해 열려 있을 뿐이다. 창을 통해 보이는 세계, 그것은 폐허로 변해버린 빈집과 확연히 구분되는 현실공간이다. 지금은 초라하게 무너져 내렸지만 한때는 이곳도 창 너머로 보이는 세계와 크게 다르지 않았다. 아직 채 뜯겨나가지 않은 반투명의 커튼 뒤로 보이는 시가 풍경, 흉측한 몰골만 남은 사각의 틀 너머로 펼쳐진 야산, 외관은 아직 멀쩡해 보이는 이웃 동네의 주택 단지, 그 너머에 우뚝 솟아있는 아파트, 이 모든 것은 잔해만 남은 실내와 확연히 비견되는 모습이다. 요컨대 폐가가 되어버린 이 빈집들도 예전에는 저 온전한 세계에 속해 있었다. 그러나 이제는 창밖으로 보이는 저 세계로 다시 돌아갈 수 없다. 무너져 내린 천정이나 뜯겨나간 벽들과 함께 이 빈집들은 구겨진 세계가 되어버렸다.

한편 완전히 뜯겨나가 사각의 틀만 남아 있는 창은 액자처럼 보이기도 한다. 그 창이 보여주는 바깥 풍경은 캔버스 위에 그려진 그림과도 같다. 잘게 조각난 벽의 파편들이 어지럽게 널려 있는 어수선한 실내에 비해 단정하게 정돈된 창밖의 모습은 상대적으로 얼마나 정갈해 보이는가. 정면에 위치한 창틀이 보여주는 바깥 세계는 한때 이곳에 살았던 쫓겨난 이들의 눈에는 가닿고 싶은 바람으로서의 세계, 요컨대 동경의 대상처럼 보인다. 이 칙칙한 빈집이 암울한 현실이라면 창틀이 보여주는 모습은 집 잃은 자들이 속하지 못한 저 너머의 세계인 셈이다. 그렇게 창틀은 어디론가 떠나버린 이 빈집의 옛 주인들의 암담한 심경에 대한 메타포가 된다.

다음은 바닥에 나뒹굴고 있는 집의 상처와 이주의 흔적들. 빈집들이 철거될 운명에 처해 있음을 알려주는 징표들은 무수히 많다. 천정의 조명등이 뜯겨나간 자국이나 누더기가 되어버린 벽지, 해체된 각종 건축자재들을 한 곳에 쌓아놓은 모습, 배선이 훤히 보일 정도로 무너져 내린 천정, 바닥에 내팽개쳐진 창문, 밟으면 버석거릴 듯이 널려 있는 깨진 유리조각, 이 모든 집의 파편들은 이제 이 빈집의 기능이 사라지고 없음을, 더 이상 집의 구실을 할 수 없음을 여실히 보여주고 있다. 조형적으로 보자면 주의를 분산시키는 잡다한 집의 파편들 때문에 구성이 어지러워질 수 있지만 중앙에 위치한 창문으로 수렴되는 원근법적 구도가 시선을 모아주고 바닥에 널린 잔해들이 덩어리로 뭉쳐 화면을 단순화시키는 효과를 낳는다. 복잡한 화면에 간결한 구조가 생겨나는 것이다. 또한 양 옆에 위치한 깔끔한 벽면에 비해 바닥에 널린 조각들의 무게감은 화면에 안정감을 실어주기도 한다. 이것이 자칫하면 어지럽고 불안정해질 수 있는 폐허의 공간에 안정된 조형성을 부여해준다.

집을 할퀴고 지나간 난폭한 철거의 잔해와 더불어 남아 있는 것은 집을 떠난 이들에게 속해 있던 거주의 흔적들이다. 「유리의 얼굴이 그려진 방 - 이문동」에는 창문 바로 아래 아이들의 눈높이에 맞추어 벽에 붙여놓은 한글 학습용 포스터와 구구단을 비롯한 각종 학습 교재가 보인다. 아이들의 방이었음을 짐작케 하는, 누더기가 되어버린 교재들이다. 「작은 의자가 놓인 거실 - 아현동」의 벽에는 결혼기념 사진으로 보이는 액자가 비스듬히 놓여 있고 중앙에는 뒤집혀 정체를 알 수 없는 또 다른 사진 액자와 훌라후프가 버려져 있다. 얼마나 체념이 깊었으면, 혹은 얼마나 급박했으면 결혼사진도 팽개치고 떠났을까, 아직 온전한 상태인 아이의 장난감마저 버려두고 말이다. 「노란 벽지로 도배된 방 - 남가좌동」에서도 처량한 이주의 흔적은 되풀이된다. 아이가 정성껏 만들었음을 한눈에 알 수 있는 물고기 모양의 모빌은 이 파괴된 방의 어린 여주인을 할퀴고 지나갔을 상심을 암시하고 있다. 「성찬이가 뛰어놀던 거실 - 왕십리동」에서 거실 구석에 놓인 탬버린과 우산, 훌라후프는 아이가 채 거둬가지 못한 자기 집에 대한 미련의 상징처럼 보인다. 「외국인 노동자 부부가 살던 방 - 상왕십리동」에도 삶의 일부였던 것들을 포기하고 떠났음을 알려주는 흔적들이 잘게 부수어진 벽 조각들과 어지럽게 섞여 있다. 가족 앨범을 비롯하여 슬리퍼와 수건, 비디오테이프, 롤러스케이트 한쪽, 심지어는 비와 먼지떨이까지 남겨두고 유랑을 떠난 것이다. 그들은 자신의 과거를 버려야만 했다. 그들이 버릴 수밖에 없었던 것은 그것뿐만이 아니다. 「현숙이가 장구를 치던 방-남가좌동」에 뒹굴고 있는 망가진 장구와 기타, 죽부인등 그들의 삶과 얽혀 있던 모든 크고 작은 물품들이 모조리 주인을 잃고 만 것이다. 그들은 떠나야만 했다. 새로운 보금자리를 찾아 희망을 품고 떠난 것이 아니라 떠밀려서 어쩔 수 없이 쫓겨났다. 재개발의 어두운 그림자가 그렇게 이 빈집들의 내부에 짙게 드리워져 있다.

작가가 빈집을 바라보는 시각은 공간을 포착하는 일관된 구도와 앵글, 폐허와 대결하는 정공법을 통해 결정된다. 그 시각이 빚어낸 결과는 폐허를 장관으로 만드는 그로테스크한 조형성과도 유사해 보인다. 파괴된 방에 비장미가 스며드는 것과도 유사하다 하겠다. 그러나 이러한 조형성은 어느새 다시 연극적 재현에서나 찾아볼 수 있는 가장된 현실감을 창출해내기에 이른다. 꾸며낸 현실에서 느낄 수 있는 어색하고 부자연스러운 정조가 개입하는 것이다. 빈집 내부의 모습을 작가가 공들여 재배치했는가, 그렇지 않은가는 중요하지 않다. 문제는 그 모습이 한결같이 집에 대한 일반의 인식을 교란시키는 데 이바지하고 있다는 점이다. 「대한민국 전도가 있는 방 - 이문동」에서 볼 수 있듯 거실 전체를 빼곡히 채운 부서진 건축자재들이 어디에서 왔는지 우리는 알 수 없다. 목재로 둘러싸인 벽면과 천정은 그대로인데 누가, 어디에서 이 파손된 벽 더미를 옮겨왔단 말인가. 그것들은 마치 바닥 전체를 여백 없이 덮기 위해 차곡차곡 쌓아놓은 것처럼 보이기도 한다. 어쨌든 이 파괴된 방들은 모두 주거공간이기를 그치고 공사판으로 둔갑한다. 그것이 이 방들의 현실성이다. 하지만 여전히 빈집 구석구석에 묻어 있는 사람의 자취들은 이 공간의 정체성을 교묘히 비튼다. 공사장이라 할 수도 없고 주거공간이라 할 수도 없는 중간지대, 낯설다 못해 공간의 물리적 현실성마저 부정하려 드는 완강한 인식의 저항이 이 빈집의 기이함을 증폭시켜주는 것이다.

이러한 기이함은 창문 너머 저편으로 보이는 그림같은 현실과의 대조를 통해 한층 강화된다. 그 기이함은 「철창이 있는 방 - 상왕십리동」이 보여주듯 철거될 집과 바깥 세계를 엄격히 구분하는 데서 오는 것이기도 하다. 이 빈 집은 바깥세계로부터 격리되어 있는 것이다. 사람이 더 이상 살지 않는 빈집들은 세상에서 유리되어 통로조차 없는 갇힌 방이 되어버렸다. 서울시내 한복판에 있으면서도 재개발 지역의 빈집들은 마치 육지로부터 고립된 섬처럼 세상에서 떨어져나간 셈이다. 지리적으로, 행정구역상으로는 서울시에 포함되지만 실제로는 그렇지 않은 기이한 지위가 이 지역의 위상을 결정한다. 이곳은 그렇게 서울시에 없는 곳이 된다. 서울에서 지워진 이곳은 그래서 기이해 보인다. ‘잊혀진 이웃’의 작품들에서 가공된 듯한 현실감, 꾸며낸 듯한 현실성이 느껴지는 것도 그런 이유 때문이다. 창 하나를 경계로 확연히 나뉘는 두 세계의 이질감이 그 가공된 현실성을 더욱 증폭시켜주고 있다.

작가는 황량한 빈집들의 모습에서 결국 망각의 문제를 환기시킨다. 주변에 살던 이웃들이 모두 어디론가 떠나버린 이곳, 남아 있는 것은 폐허뿐이지만 그마저도 조만간 사라질 운명이다. 빈집들은 주인에 대한 기억을 아직은 희미하게 보존하고 있다. 그들이 미처 추스르지 못하고 남겨놓은 일상용품이 아니더라도 벽 구석구석에 묻어 있는 삶의 채취들이 그것을 붙들어두고 있는 것이다. 하지만 재개발이 진행되는 과정에서 그마저도 새로 들어설 건물들과 함께 사라질 운명이다. 이웃사람들의 보금자리였던 집들이 철거됨과 동시에 사람 자체도 망각되어 가는 재개발의 현실, 그래서 작가는 작업노트에 “누구도 그들에게 관심을 기울이지 않는다”고 냉소적으로 적는다. 그 망각을 일깨워준 것은 빈집의 공허함이다. 있을 때는 모르다가 없으면 알게 되는 것이 존재감 아니던가. 하여 이 빈집들에서 작가가 받은 트라우마는 무너진 벽이나 떨어져 나간 창틀, 구겨진 벽지, 어지럽게 널려 있는 벽돌조각들에서 오는 것이 아니라 아무도 없음, 요컨대 공허에서 온다. 그 공허가 상처를 주는 까닭은 타인에 대한 망각을 물려줄 터이기 때문이다. 문제는 그래서 삶의 터전을 잃고 제 집에서마저 쫓겨나 고통 받는 타인이 많아지는 상황과 더불어 타인의 고통에 대해 점차 우리 스스로 둔감해져가는 현실이다. 그렇게 무디고 둔탁해져가는 이유는 망각 때문이다. 하여 망각을 걷어내기 위해 작가는 공허를 환기시킨다. 창문 너머에서 들어오는 빛이 빈집 구석구석까지 샅샅이 훑고 지나가지만 아무도 없다. 바깥세상의 빛이 탐지해내는 것은 그들이 남기고 간 흔적과 폐기의 징후로 방안 가득 쌓인 집의 부속품들뿐이다. 그렇게 없음을 환기시킨다고 해서 망각을 이겨낼 수 있을까. 작가는 그 점에 대해 명쾌한 답을 갖고 있지는 않은 듯하다. 다만 망각과 싸우기 위해 빈집 가득 공허를 채워 이를 보여 주려 할 뿐이다. 요컨대 방안 가득 널려 있는 폐허의 기호들은 공허를 환기시켜주기 위한 소품들이라 할 수 있다. 사라진 타인들을 기억에 붙잡아둘 수 있는 수단은 그것뿐이므로, 다시 말해 그들의 부재는 그들이 남겨놓은 흔적을 통해서만 알려질 수 있으므로. 이처럼 작가가 빈집에서 진정으로 목격한 것은 파손된 집의 잔해가 아니라 그들의 부재라 할 수 있다. 그렇게 작가는 부재를 환기시킴으로써 망각과 맞서고 있는 것이다.

Signs of Absence against Forgetting

In the Forgotten Neighbors series, Choi Wu-yeong visually explores the redevelopment going on in the heart of Seoul. It's been quite a while since so many different social problems arose surrounding urban redevelopment, culminating in the death of several people surrounding the forced redevelopment and the removal of buildings in Seoul in 2009. It is clear that Seoul's city center redevelopment is not all about the tearing down of old buildings which have diminished the fine view of the city simply to build them up once again to be in harmony with the current landscape. A city is a living, breathing entity that never stops changing, contracting and expanding time and again, an area that can undergo change as a response to the changes in people's lives. And redevelopment is the least effective tool to bring about such changes. Yet redevelopment is a fact of life and so the challenge is to find the best way to reduce its side effects. If development is to continue making new and artificial environments for life, separation will necessarily be involved. When this separation divides people's lives into a "before" and "after," they are bound to be upset because they are being suddenly thrown into a strange and unfamiliar environment. Furthermore, the reality of separation that is created through redevelopment does not stop at the creation of a strange new environment but results in driving out people who have lived there. This is especially true when taken in combination with Korean society's particular characteristics. Still, the artist manages to capture the ruins of some of these places where people once lived from the same point of view in each of the artworks.

There are many examples of keeping a photographic record of the changes brought about in a city caused by redevelopment. Charles Marville, the man responsible for photographing Paris as it was being transformed by urban planning started in the 1850s, and Eugéne Atget, the man responsible for recording the Paris of old in the 1900s, are the fathers of this art form. Both Marville and Atget had a specific goal: to preserve a record of scenes from the old city. The only difference between the two men was that Marville was commissioned by the government and Atget did the work of his own volition. Nevertheless, they defined the meaning of their recording activity through their intention to preserve the city as an archive before it disappeared. In Korea, there are various types of records concerning cities, some of which were initiated by the government and some of which were the result of a particular photographer's personal interest. As a result of the developmental dictatorship that prevailed throughout the 1960s and 70s, the residential environment in Seoul changed rapidly. Some of these photos are still with us today. While this is a relief, it is insufficient because the points of view were not diverse enough and recorded only parts of the urban milieu. Choi Wu-yeong's work is noteworthy not only because he introduces an interesting point of view by which to look at Seoul in the first decade of this century, but also because he extends the range of our interest, which in turn enriches the photographic record of Seoul.

While it is true that the primary meaning of Forgotten Neighbors lies in the fact that it is a record of a city, it does not stop there strictly for the purpose of producing straightforward, dry reference materials. The way in which the artist records the urban scenes in his artwork is enlightening and persuading. At the same time it informs people of the negative results of redevelopment. Starting with his sociological interest, the artist sublimates the mood from those empty houses into lonely lyricism. Yet to find lyricism in houses from which people have been driven out is, in a sense, contradictory - decadent even. Most of all, it is contradictory because of the fact that a stolen life lies concealed in those houses. Behind the lofty causes and economic benefits bestowed upon only a small number of people are many more people's very real agony as well as the negative consequences from the expulsion of those people. The calm format and symbolism in Choi's art that helps us notice this fact may be the real power in creating this sense of lonely lyricism, and the same element which distinguishes his art from persuasive images which almost seem like an elaborate message delivered in the form of a lecture.

What we initially see in one of these series is a window at the front of an empty house. The artist boldly excludes any exterior elements, choosing instead to show only the interior, especially the living room, and displaying it as a set pattern of redevelopment. You can't see common symbols of redevelopment like parts of broken buildings or piles of stones (objects which are likely to be scattered on the road) or broken walls in Choi's photos. Rather, small everyday items are scattered around inside: torn-down wallpaper, a collapsed ceiling, the debris from broken walls. Also, a window near the front is incomplete. In truth, the window frame is heavily damaged, so it is just a wall with a hole in the building structure. Glass that once prevented outside air from getting in was also broken, and so the dilapidated-looking window is merely "open" to the outer world. The window separates the reality of the outside world from the ruined interior. Although the house is now totally run down, there was a time when it was not very different from the rest of the world. Street views seen behind the translucent curtain (which wasn't torn down), a hill over the square frame, the neighborhood housing complex (which somehow still looks okay outside), and apartment buildings that are standing high beyond them. Yet all these images stand in stark contrast to the ruined interior. In short, all the empty houses in the series once belonged to the intact world, though they can't return to the world which is pictured on the other side of the window ever again. With the collapsed ceiling and the broken walls, the empty houses now belong to a ruined world.

In a way, the window with nothing left to it but the outer square part looks like a picture frame. The landscape outside the window is not unlike a painting on a canvas. In contrast to the chaotic interior, where small debris from the broken wall lies scattered about, everything outside the window looks perfectly arranged. The view through the window frame seems like one we all aspire to reach, an object of yearning to the eyes for those who once lived here but have now been driven away. If this dull, empty house is the dark reality, the scene through the window frame represents the world beyond reality, a place that people can never reach. In that way, the window frame becomes a metaphor for the previous owners' depressing state of mind about this empty house.

The house is heavily scarred and traces of migration can be seen all over the floor. There are countless signs that indicate the empty house is destined to be torn down. A light bulb hangs precariously from the ceiling. There is tattered wallpaper and various deconstructed building materials in one corner. Wires can be seen in the ceiling overhead, windows have been smashed on the fl oor so that pieces of broken glass lie everywhere. All this debris is a clear indication that the empty houses in this series cannot function as homes any longer. From a formative point of view, the structure in the photos may seem confusing because of all the miscellaneous pieces strewn about, which diverts the viewer's attention. Regardless, the composition, based on the laws of perspective and which converge in the center of the window, as well as with the debris scattered all over the floor, simplifies the photo. Thus, a simple structure is born from a complicated photo. Also, compared to the very nice surfaces of the two walls on either side, the weight of the pieces spread on the floor help impart a sense of stability to the picture. This provides a stabilizing effect for the ruined place as a whole, which otherwise would have been confusing and unstable. Along with the debris, there are traces that someone once lived here, indicating that someone was violently removed from the house. "The Room with Yuri's Painted Face - Imun-dong," contains a variety of study materials, including posters for learning the Korean language and multiplication tables at the eye level of a child, right under the window. The study materials appear withered and old and lead one to believe that this was once a child's room. In "A Living Room with a Small Chair - Ahyeon-dong," a picture frame that resembles a wedding photo is placed diagonally on a wall, and in the center of the living room is another picture frame (unrecognizable because it is upside down) and a hula hoop. This raises several questions such as why the people left behind a wedding photo and a perfectly good child's toy, how upset were they, and how quickly did they leave the house. In "A Room Papered with Yellow Wallpaper - Namgajwa-dong," similarly desolate traces of migration can be seen. The fish-shaped mobile which was clearly made by the loving, caring hands of a child, and the pink schoolbag placed to the right capture the sorrow of the little female owner who once lived in this now dilapidated room. In "The Living Room Where Seong-chan Played - Wangsimni-dong," a tambourine, umbrella, and hula hoop seem like symbols of the child's lingering attachment to the house. In "A Room Where a Foreign Laborer Couple Lived - Sangwangsimnidong," scattered traces among the broken pieces of the walls indicate that they relinquished some part of their lives before they left. They went wandering, leaving their a slipper, a towel, a videotape, a single roller skate, a broomstick, and a feather duster behind. Indeed, they had to do away with even more things. Then there are the shattered parts of the janggu (Korean drum), a guitar, and a Dutch wife made of bamboo, all of which can be seen in "The Room Where Hyeon-suk Played the Janggu - Namgajwa-dong," Both large and small articles that were closely related to those people's lives have all lost their owners. These people had to leave, but not for a new place replete with hope. Quite the opposite, the dark shadow of redevelopment hangs around these empty houses like a noose.

The viewpoint by which the artist looks at empty houses is determined by the consistent composition and angle, as well as a "frontal attack" against the ruins. The resulting viewpoint is something analogous to a grotesque formativeness that turns the ruins into a spectacle. It is actually quite similar to a tragic beauty sinking into a destroyed room. However, such formativeness silently creates a disguised sense of reality that can be found in the theater. An awkward and unnatural mood is involved in the photos. It is not important whether the artist carefully rearranged the scenes in empty houses or not. What matters is that those scenes contribute to confusing people's general idea about what a home represents, such as in "A Room with a Map of the Republic of Korea - Imun-dong." With this piece we don't know where the broken building materials came from that fill the living room. The walls and ceiling are intact, but who brought this pile of broken walls and from where? It almost looks as if things were piled one on top of another to cover the whole floor. Whatever the case, these destroyed rooms in the photos cease to be residential spaces and are actually construction sites. That is the reality of these rooms. Still, the leftover traces of people can be seen here and there in the empty houses and oddly distort the identity of these spaces. Thus, these spaces lie somewhere in limbo between construction sites and residential places. In addition to their strangeness, the resistant attitude to deny even the physical reality of the spaces amplifies the strangeness of the empty houses.

Such peculiarity is heightened even more through the contrast with the picturesque reality seen through the window. The oddity comes from the fact that the artist strictly separates the house (which will be torn down) from the outer world, as he does in "A Room with a Steel-Barred Window - Sangwangsimni-dong." This empty house is isolated from the outer world and is a place where no one lives anymore. Isolated from the world, it is now like a prison without an outlet whatsoever. Although those empty houses are in the center of Seoul, they are still separated from the world like a remote island is from the main land. Their odd position of being included in Seoul geographically and administratively but in truth not part of Seoul renders them eligible for redevelopment status. As such, this area becomes a place that no longer exists in Seoul and so this area seems strange. That is also why we can feel a fabricated or made-up reality in the Forgotten Neighbors series. A s sense of heterogeneousness about the two worlds with one single window serving as the border amplifies such a fabricated reality.

The artist is reminding us about the issue of forgetting. In this place where every neighbor has left for somewhere else, only ruins are left behind and even they are destined to disappear soon. Empty houses still preserve a vague memory of their former owners. Besides the everyday articles they left behind, other traces of life can be found in every part of the memory-laden walls. Sadly, these memories are also destined to disappear with the erection of new buildings. The reality is that in the process of redevelopment our neighbors are forgotten when the houses they once lived in are torn down. That is why the artist cynically writes "Nobody is interested in them." What makes viewers realize the act of forgetting is the emptiness of the empty houses. While we are conscious of one's presence when they are away from us, we are not conscious of their presence when they stay with us. The trauma emanating from these empty houses is therefore not the result of broken walls, torn-off window frames, crumpled wallpaper, or scattered pieces of brick. It comes from the fact that no one is there. In short, it comes from emptiness. The reason that emptiness causes such pain is that it makes us forget about others. The problem is that we become insensitive to other people's pain, while an increasing number of people are driven from their own homes and suffer greatly as a result. Forgetfulness leads us to become so dull and desensitized to this all, and so the artist reminds us of this emptiness in order to rid ourselves of this forgetfulness. The light coming from the window passes through every corner of the empty house, but still there is no one present. The light from the outside world detects traces of the former residents as well as signs of their removal, while broken parts of the house that fill up the room are clear signs the house was abandoned. Can we overcome the tendency to forget just by reminding us of their absence? It doesn't seem that the artist has a clear answer. He is merely trying to demonstrate that the house is filled with emptiness in order to fight against forgetting. In short, the signs of ruin throughout the room are props to remind people of emptiness, the only way to "contain" those who have already disappeared. In other words, the former residents' absence can only be revealed through their lingering traces; what the artist actually witnessed in the empty houses is not the ruins of destroyed homes but the absence of their former residents. By reminding us of absence, the artist confronts the act of forgetting.

Text by Park Pyeong-jong an aesthetician and photo critic

In the Forgotten Neighbors series, Choi Wu-yeong visually explores the redevelopment going on in the heart of Seoul. It's been quite a while since so many different social problems arose surrounding urban redevelopment, culminating in the death of several people surrounding the forced redevelopment and the removal of buildings in Seoul in 2009. It is clear that Seoul's city center redevelopment is not all about the tearing down of old buildings which have diminished the fine view of the city simply to build them up once again to be in harmony with the current landscape. A city is a living, breathing entity that never stops changing, contracting and expanding time and again, an area that can undergo change as a response to the changes in people's lives. And redevelopment is the least effective tool to bring about such changes. Yet redevelopment is a fact of life and so the challenge is to find the best way to reduce its side effects. If development is to continue making new and artificial environments for life, separation will necessarily be involved. When this separation divides people's lives into a "before" and "after," they are bound to be upset because they are being suddenly thrown into a strange and unfamiliar environment. Furthermore, the reality of separation that is created through redevelopment does not stop at the creation of a strange new environment but results in driving out people who have lived there. This is especially true when taken in combination with Korean society's particular characteristics. Still, the artist manages to capture the ruins of some of these places where people once lived from the same point of view in each of the artworks.

There are many examples of keeping a photographic record of the changes brought about in a city caused by redevelopment. Charles Marville, the man responsible for photographing Paris as it was being transformed by urban planning started in the 1850s, and Eugéne Atget, the man responsible for recording the Paris of old in the 1900s, are the fathers of this art form. Both Marville and Atget had a specific goal: to preserve a record of scenes from the old city. The only difference between the two men was that Marville was commissioned by the government and Atget did the work of his own volition. Nevertheless, they defined the meaning of their recording activity through their intention to preserve the city as an archive before it disappeared. In Korea, there are various types of records concerning cities, some of which were initiated by the government and some of which were the result of a particular photographer's personal interest. As a result of the developmental dictatorship that prevailed throughout the 1960s and 70s, the residential environment in Seoul changed rapidly. Some of these photos are still with us today. While this is a relief, it is insufficient because the points of view were not diverse enough and recorded only parts of the urban milieu. Choi Wu-yeong's work is noteworthy not only because he introduces an interesting point of view by which to look at Seoul in the first decade of this century, but also because he extends the range of our interest, which in turn enriches the photographic record of Seoul.

While it is true that the primary meaning of Forgotten Neighbors lies in the fact that it is a record of a city, it does not stop there strictly for the purpose of producing straightforward, dry reference materials. The way in which the artist records the urban scenes in his artwork is enlightening and persuading. At the same time it informs people of the negative results of redevelopment. Starting with his sociological interest, the artist sublimates the mood from those empty houses into lonely lyricism. Yet to find lyricism in houses from which people have been driven out is, in a sense, contradictory - decadent even. Most of all, it is contradictory because of the fact that a stolen life lies concealed in those houses. Behind the lofty causes and economic benefits bestowed upon only a small number of people are many more people's very real agony as well as the negative consequences from the expulsion of those people. The calm format and symbolism in Choi's art that helps us notice this fact may be the real power in creating this sense of lonely lyricism, and the same element which distinguishes his art from persuasive images which almost seem like an elaborate message delivered in the form of a lecture.

What we initially see in one of these series is a window at the front of an empty house. The artist boldly excludes any exterior elements, choosing instead to show only the interior, especially the living room, and displaying it as a set pattern of redevelopment. You can't see common symbols of redevelopment like parts of broken buildings or piles of stones (objects which are likely to be scattered on the road) or broken walls in Choi's photos. Rather, small everyday items are scattered around inside: torn-down wallpaper, a collapsed ceiling, the debris from broken walls. Also, a window near the front is incomplete. In truth, the window frame is heavily damaged, so it is just a wall with a hole in the building structure. Glass that once prevented outside air from getting in was also broken, and so the dilapidated-looking window is merely "open" to the outer world. The window separates the reality of the outside world from the ruined interior. Although the house is now totally run down, there was a time when it was not very different from the rest of the world. Street views seen behind the translucent curtain (which wasn't torn down), a hill over the square frame, the neighborhood housing complex (which somehow still looks okay outside), and apartment buildings that are standing high beyond them. Yet all these images stand in stark contrast to the ruined interior. In short, all the empty houses in the series once belonged to the intact world, though they can't return to the world which is pictured on the other side of the window ever again. With the collapsed ceiling and the broken walls, the empty houses now belong to a ruined world.

In a way, the window with nothing left to it but the outer square part looks like a picture frame. The landscape outside the window is not unlike a painting on a canvas. In contrast to the chaotic interior, where small debris from the broken wall lies scattered about, everything outside the window looks perfectly arranged. The view through the window frame seems like one we all aspire to reach, an object of yearning to the eyes for those who once lived here but have now been driven away. If this dull, empty house is the dark reality, the scene through the window frame represents the world beyond reality, a place that people can never reach. In that way, the window frame becomes a metaphor for the previous owners' depressing state of mind about this empty house.

The house is heavily scarred and traces of migration can be seen all over the floor. There are countless signs that indicate the empty house is destined to be torn down. A light bulb hangs precariously from the ceiling. There is tattered wallpaper and various deconstructed building materials in one corner. Wires can be seen in the ceiling overhead, windows have been smashed on the fl oor so that pieces of broken glass lie everywhere. All this debris is a clear indication that the empty houses in this series cannot function as homes any longer. From a formative point of view, the structure in the photos may seem confusing because of all the miscellaneous pieces strewn about, which diverts the viewer's attention. Regardless, the composition, based on the laws of perspective and which converge in the center of the window, as well as with the debris scattered all over the floor, simplifies the photo. Thus, a simple structure is born from a complicated photo. Also, compared to the very nice surfaces of the two walls on either side, the weight of the pieces spread on the floor help impart a sense of stability to the picture. This provides a stabilizing effect for the ruined place as a whole, which otherwise would have been confusing and unstable. Along with the debris, there are traces that someone once lived here, indicating that someone was violently removed from the house. "The Room with Yuri's Painted Face - Imun-dong," contains a variety of study materials, including posters for learning the Korean language and multiplication tables at the eye level of a child, right under the window. The study materials appear withered and old and lead one to believe that this was once a child's room. In "A Living Room with a Small Chair - Ahyeon-dong," a picture frame that resembles a wedding photo is placed diagonally on a wall, and in the center of the living room is another picture frame (unrecognizable because it is upside down) and a hula hoop. This raises several questions such as why the people left behind a wedding photo and a perfectly good child's toy, how upset were they, and how quickly did they leave the house. In "A Room Papered with Yellow Wallpaper - Namgajwa-dong," similarly desolate traces of migration can be seen. The fish-shaped mobile which was clearly made by the loving, caring hands of a child, and the pink schoolbag placed to the right capture the sorrow of the little female owner who once lived in this now dilapidated room. In "The Living Room Where Seong-chan Played - Wangsimni-dong," a tambourine, umbrella, and hula hoop seem like symbols of the child's lingering attachment to the house. In "A Room Where a Foreign Laborer Couple Lived - Sangwangsimnidong," scattered traces among the broken pieces of the walls indicate that they relinquished some part of their lives before they left. They went wandering, leaving their a slipper, a towel, a videotape, a single roller skate, a broomstick, and a feather duster behind. Indeed, they had to do away with even more things. Then there are the shattered parts of the janggu (Korean drum), a guitar, and a Dutch wife made of bamboo, all of which can be seen in "The Room Where Hyeon-suk Played the Janggu - Namgajwa-dong," Both large and small articles that were closely related to those people's lives have all lost their owners. These people had to leave, but not for a new place replete with hope. Quite the opposite, the dark shadow of redevelopment hangs around these empty houses like a noose.

The viewpoint by which the artist looks at empty houses is determined by the consistent composition and angle, as well as a "frontal attack" against the ruins. The resulting viewpoint is something analogous to a grotesque formativeness that turns the ruins into a spectacle. It is actually quite similar to a tragic beauty sinking into a destroyed room. However, such formativeness silently creates a disguised sense of reality that can be found in the theater. An awkward and unnatural mood is involved in the photos. It is not important whether the artist carefully rearranged the scenes in empty houses or not. What matters is that those scenes contribute to confusing people's general idea about what a home represents, such as in "A Room with a Map of the Republic of Korea - Imun-dong." With this piece we don't know where the broken building materials came from that fill the living room. The walls and ceiling are intact, but who brought this pile of broken walls and from where? It almost looks as if things were piled one on top of another to cover the whole floor. Whatever the case, these destroyed rooms in the photos cease to be residential spaces and are actually construction sites. That is the reality of these rooms. Still, the leftover traces of people can be seen here and there in the empty houses and oddly distort the identity of these spaces. Thus, these spaces lie somewhere in limbo between construction sites and residential places. In addition to their strangeness, the resistant attitude to deny even the physical reality of the spaces amplifies the strangeness of the empty houses.

Such peculiarity is heightened even more through the contrast with the picturesque reality seen through the window. The oddity comes from the fact that the artist strictly separates the house (which will be torn down) from the outer world, as he does in "A Room with a Steel-Barred Window - Sangwangsimni-dong." This empty house is isolated from the outer world and is a place where no one lives anymore. Isolated from the world, it is now like a prison without an outlet whatsoever. Although those empty houses are in the center of Seoul, they are still separated from the world like a remote island is from the main land. Their odd position of being included in Seoul geographically and administratively but in truth not part of Seoul renders them eligible for redevelopment status. As such, this area becomes a place that no longer exists in Seoul and so this area seems strange. That is also why we can feel a fabricated or made-up reality in the Forgotten Neighbors series. A s sense of heterogeneousness about the two worlds with one single window serving as the border amplifies such a fabricated reality.

The artist is reminding us about the issue of forgetting. In this place where every neighbor has left for somewhere else, only ruins are left behind and even they are destined to disappear soon. Empty houses still preserve a vague memory of their former owners. Besides the everyday articles they left behind, other traces of life can be found in every part of the memory-laden walls. Sadly, these memories are also destined to disappear with the erection of new buildings. The reality is that in the process of redevelopment our neighbors are forgotten when the houses they once lived in are torn down. That is why the artist cynically writes "Nobody is interested in them." What makes viewers realize the act of forgetting is the emptiness of the empty houses. While we are conscious of one's presence when they are away from us, we are not conscious of their presence when they stay with us. The trauma emanating from these empty houses is therefore not the result of broken walls, torn-off window frames, crumpled wallpaper, or scattered pieces of brick. It comes from the fact that no one is there. In short, it comes from emptiness. The reason that emptiness causes such pain is that it makes us forget about others. The problem is that we become insensitive to other people's pain, while an increasing number of people are driven from their own homes and suffer greatly as a result. Forgetfulness leads us to become so dull and desensitized to this all, and so the artist reminds us of this emptiness in order to rid ourselves of this forgetfulness. The light coming from the window passes through every corner of the empty house, but still there is no one present. The light from the outside world detects traces of the former residents as well as signs of their removal, while broken parts of the house that fill up the room are clear signs the house was abandoned. Can we overcome the tendency to forget just by reminding us of their absence? It doesn't seem that the artist has a clear answer. He is merely trying to demonstrate that the house is filled with emptiness in order to fight against forgetting. In short, the signs of ruin throughout the room are props to remind people of emptiness, the only way to "contain" those who have already disappeared. In other words, the former residents' absence can only be revealed through their lingering traces; what the artist actually witnessed in the empty houses is not the ruins of destroyed homes but the absence of their former residents. By reminding us of absence, the artist confronts the act of forgetting.

최우영 Choi Wu-yeong

1977 부산 출생

2010 홍익대학교 산업미술대학원 사진디자인전공 졸업

개인전

2014 에이트리갤러리, 서울

........대안공간 루트, 평택

2010 가나아트 스페이스, 서울

........문화매개공간 쌈, 부산

단체전

2013 사진,고덕의 삶을 기록하다, 고덕면주민센터, 평택

2009 Post Photo, 토포하우스, 서울

2009 아시아프, 구 기무사, 서울

2008 Post Photo, 토포하우스, 서울

2005 Puzzling Rainbow, 갤러리보우, 울산

........울산한일현대미술제, 울산문화예술회관, 울산

2003 한일현대미술교류전, 부산문화회관, 부산

1977 부산 출생

2010 홍익대학교 산업미술대학원 사진디자인전공 졸업

개인전

2014 에이트리갤러리, 서울

........대안공간 루트, 평택

2010 가나아트 스페이스, 서울

........문화매개공간 쌈, 부산

단체전

2013 사진,고덕의 삶을 기록하다, 고덕면주민센터, 평택

2009 Post Photo, 토포하우스, 서울

2009 아시아프, 구 기무사, 서울

2008 Post Photo, 토포하우스, 서울

2005 Puzzling Rainbow, 갤러리보우, 울산

........울산한일현대미술제, 울산문화예술회관, 울산

2003 한일현대미술교류전, 부산문화회관, 부산

We all in the Truth 전

We all in the Truth 전

최우영 Choi Wu-yeong 개인전

최우영 Choi Wu-yeong 개인전