송은 아트큐브에서는 2014-2015 전시지원 프로그램 선정작가인 김진희 개인전 ‘이름 없는 여성, She’를 선보인다. 작가는 첫 경험이나 성적 욕망 등 20대 여성의 성에 관심을 갖고 그들의 경험에 대한 기억, 상처, 트라우마를 여성을 촬영한 사진으로 드러낸다. 특히, 여성과 한 화면 안에 담긴 텍스트는 사진 속 인물의 이야기에서 발췌한 문장으로 사진을 실로 꿰매는 작업을 통해 글씨를 새겨 넣는다. 이는 수치스럽거나 감추고 싶은 기억이나 상처를 치유하기 위한 행위로 시작되었으나 반복되는 바느질을 통해 정작 본인의 사진에 상처를 입히고, 상처와 치유의 과정이 반복적으로 순환되고 있음을 설명한다.

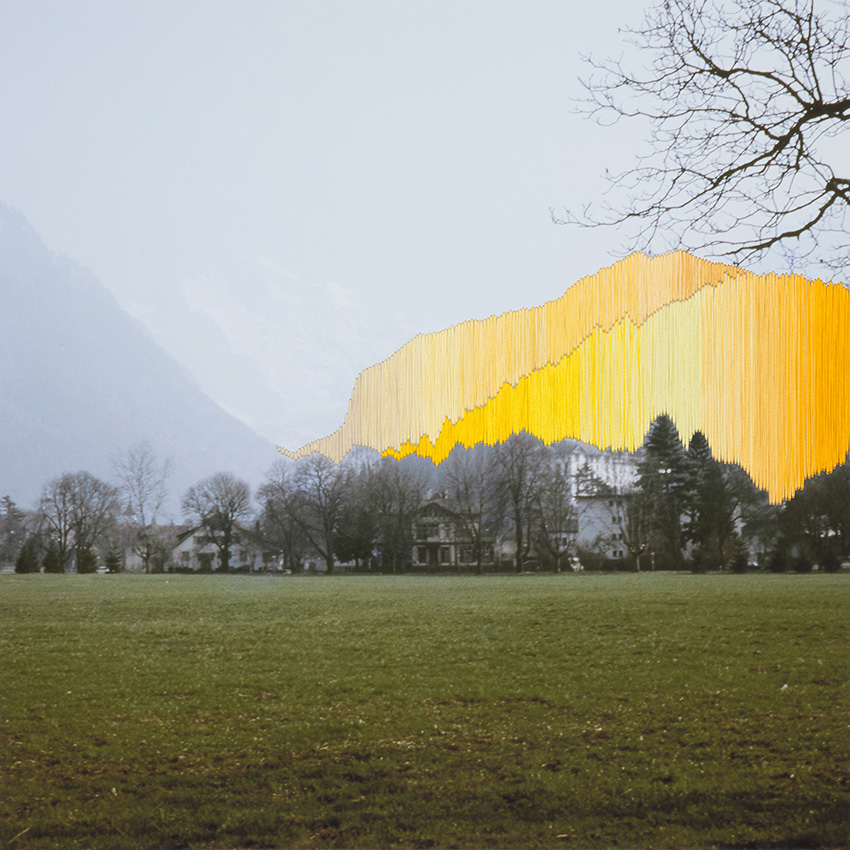

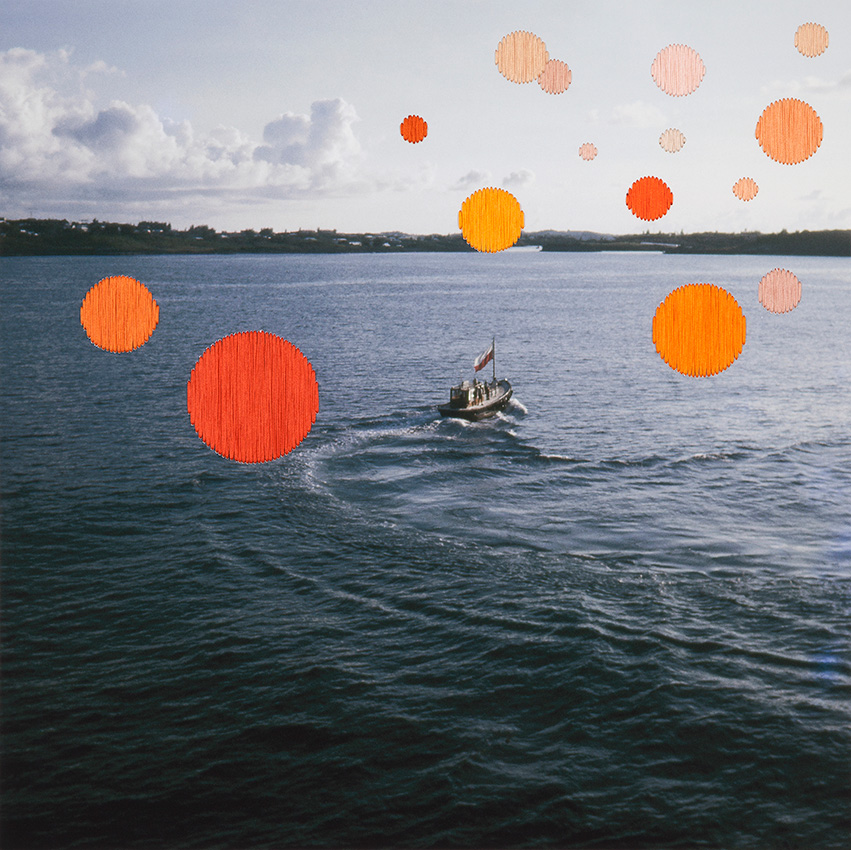

이번 전시를 통해 작가는 20대 여성의 모습과 그들의 언어를 통해 과거에 대한 기억과 상처, 트라우마를 바라보는 [She] 시리즈와 전라남도 진도의 풍경을 통해 돌이킬 수 없는 사고로 슬픔의 계절이 되어버린 4월을 시각화한 [April] 시리즈를 선보인다. 작가는 슬픔, 고통 등 비극을 경험했을 때 기억을 억압하고 잠식시키기보다 실을 엮고 매듭짓는 행위를 통해 상처를 덮고 치유하고자 한다.

이번 전시를 통해 작가는 20대 여성의 모습과 그들의 언어를 통해 과거에 대한 기억과 상처, 트라우마를 바라보는 [She] 시리즈와 전라남도 진도의 풍경을 통해 돌이킬 수 없는 사고로 슬픔의 계절이 되어버린 4월을 시각화한 [April] 시리즈를 선보인다. 작가는 슬픔, 고통 등 비극을 경험했을 때 기억을 억압하고 잠식시키기보다 실을 엮고 매듭짓는 행위를 통해 상처를 덮고 치유하고자 한다.

이름 없는 여성, She

“시시한 것 같아 보여도 어느 날은 그게 또 전혀 아니니까. 나를 납득시키기 위해 수많은 문장들을 고쳤다 쓰고 위에 덧대어야 한다. 터져 나오는 웃음은 너무나 치사해, 싫어,”

“정말은 밤길이 무서웠던게 아니었어요. 나를 잊어버리고 가는게 무서웠어요. 그래도 역시 나는 잊혀졌어요. 말을 했지만. 나는 너무나도 가벼웠나봐요. 그렇게 쉽게 잊고, 쉽게 말하는, 말을 했지만”

[’She’ 시리즈 중, 일부 대화글 발췌]

현대미술에서 여성이라는 주제는 가부장적인 제도의 구조적 모순을 인지하고 남성 중심의 문화에 도전하는 방식에서 1970년대 전후 미국 페미니스트들을 중심으로 확산되었다. 이전까지 성적인 억압으로 소외되었던 여성의 신체는 여성이 바라보는 성(gender/sexuality)에 대한 인식을 탐구하는 주된 소재가 되었으며 그들의 비평적 태도는 역사적으로 저평가된 여성의 가사 노동인 바느질, 장식미술, 실용 공예 등을 미술 안으로 수용시키는데 일조한다. 이러한 초기 페미니즘 미술은 신체미술, 퍼포먼스, 설치미술 등으로 대부분 급진적이고 직설적인 화법이 주를 이뤘다. 그리고 80년대 중반부터는 매스 미디어, 영화 같은 공적 이미지에 투영된 여성상을 차용하거나 전복시키는 방식으로 발전하기에 이른다. 그 대표적인 예로서, 우리는 로라 멀비의 [시각적 쾌락과 서사영화], 신디 셔먼의 [무제 영화 스틸], 대중매체를 원천으로 하는 사진들을 차용한 바바라 크루거의 작품들을 떠올릴 수 있다. 물론 현재에도 여성의 이미지와 여성에 의한 이미지를 복권하기 위한 시도들은 여러 예술가들을 통해 보여지고 있다. 그러나 수십년의 시간 동안 우리는 여성 예술가의 작업들이 단순한 논리와 형태로만 존재하지 않으며 따라서 이제 이런 모든 시도들을 페미니즘 미술로 단정짓기도 어려워졌다.

이제 갓 서른이 된 김진희는 20대의 한국 여성을 카메라에 꾸준히 담아왔다. 그리고 이번 전시를 통해 그녀는 풋풋한 20대의 첫 경험이나 여성의 성적 욕망에서 한걸음 더 나아가 그(녀)들의 과거에 대한 기억, 상처, 트라우마를 진지하게 바라보려 한다. 김진희의 신작 [She]에는 9명의 인물사진에 촘촘히 박힌 제목들이 먼저 눈에 띈다. 잡지 커버나 광고 문구처럼 이 텍스트는 무언의 메시지를 강렬히 던지지만 우리는 좀처럼 그 의미를 쉽게 이해하기 힘들다. 다만 김진희가 이들과 나눈 짧은 대화나 편지를 바탕으로 우리는 이 모호한 텍스트가 어디서 출몰한 것인지 짐작할 따름이다. 이런 김진희의 사진이 유독 흥미로운 건, 그들의 몸짓과 언어가 섞인 사진 텍스트로 인해 여성 특유의 섬세한 감성과 심리가 독특하게 표현되었기 때문이다. 여기서 텍스트는 시인의 언어처럼 눈앞의 대상을 묘사하는 것이 아니라 여성의 관념을 자극하는 특수한 시각언어로 자리한다. 이와 유사하게 우리는 여성에 대한 통념을 불식시키는 방법으로 사진과 텍스트를 조합해 온 작가로 바바라 크루거를 연관시켜 볼 법하다. 크루거의 [우리는 당신의 문화에 대해 자연이 되지 않겠다. We won’t Play Nature to Your Culture](1983)는 나뭇잎으로 눈을 가린 채 일광욕을 하는 젊은 여성의 사진 위에 문장을 적는 식으로 남성/여성의 대립만큼이나 뿌리 깊은 자연/문화의 대립을 시각화 시켜왔다. 그녀의 다소 냉소적이며 직설적인 문구는 그 당시 미국 사회에 뿌리 깊게 박혀있는 성차와 고정관념을 타파하는 방법이었던 것이다. 이는 “즉 남성이 행위자일 때 여성은 수동적인 대상이고, 남성이 의미의 발화자이자 제작자인 반면, 발화의 대상인 여성은 의미의 담지자에 불과하다”라는 시각의 성적 역학 관계, 즉 “이전까지 젊은 여성은 시각의 대상이지 주체가 아니다” 임을 알려준다.

그렇다면 이미지와 텍스트를 상이하게 충돌시키는 방법을 통해 김진희가 보여주고자 하는 것은 무엇일까? 크루거의 사진 텍스트가 선언적인 광고와 같다면 김진희의 작업은 명증적인 것을 거부하는 문학이나 시를 닮았다. 이 시리즈에 등장하는 젊은 여성들은 시각적 욕망의 대상이면서 동시에 발언하는 주체이다. 그러나 작가는 그녀들이 나눈 솔직한 대화들을 짧은 몇 줄의 문구로 축소시키고 다시 여러 언어로 번역하면서 본연의 메시지를 가리거나 숨겨버린다. 김진희의 첫 시리즈인 [속삭임/속삭이기whisper/ing (2009-2013)] 처럼, 그녀들의 대화는 여기서도 완전히 발화되지 못한 웅얼거림과 같다. 또한 이 시리즈 제목인 삼인칭 대명사 ‘She’는 ‘조용히 해’라는 감탄사 ‘쉬~’를 떠올리게도 한다. 당혹스럽지만 은밀하고, 명료하지만 충분히 설명되지 않는 뉘앙스. 여기에 그녀들이 던지는 강렬한 응시는 ‘모든 걸 설명하지 않아도 이해해줘’라는 제스처로 우리를, 아니 그들을 당혹스럽게 만든다. ‘역시 알다가도 모르는 게 여자야’라는 남자들의 푸념을 떠올리게 되는 건 이제껏 여성이 취한 대화 방식이 이렇듯이 절제되고 상징적이기 때문일 것이다. 바로 이 지점에서 여성은 말초적 쾌락에 순응하는 대상이 아닌 ‘이름 없는 타자’로서 등장하고 있음을 알 수 있다. 그리고 우리는 이 시리즈의 여성(=She)이 어느 쪽으로도 예속되지 못하는 의미의 발화자이자 동시에 담지자임을 눈여겨 볼 필요가 있다.

앞서 언급한 것처럼 김진희의 미완인 텍스트와 기하학적 패턴들은 감성적, 심리적 상황을 연출하지만 이는 언제나 모순적으로 드러난다. 그리고 이러한 모호함(웅얼거림 같은)은 수차례 반복적으로 실로 꿰매는 작업과정을 통해 여실히 드러난다. 주지하다시피 장시간 되풀이 한 바느질은 통상적으로 몇 장의 사진을 얻기 위해 촬영했던 작가의 예전 경험과는 사뭇 다르다. 마치 여러 번 문장을 쓰고 고치듯이 사진 표면에 실로 덧대는 반복적인 행위는 긴 노동의 시간을 필요로 하며 이로 인하여 그들이 토로한 비밀스런 기억들을 들추고 감추어야 하는 책임은 오롯이 김진희의 몫일 수 밖에 없다. 그리고 역설적이게도 그녀들의 이야기(또는 목소리)를 실로 입히는 이 지난한 과정은 필연적으로 사진 원본을 파손시키면서 거듭난다. 누군가의 상처를 덧대어 치유하는 행위가 반대로는 본인의 사진에 상처를 입히고 마는 것이다. 엉기성기 거칠게 박힌 사진의 뒷면은 그 앞면에 고이 수놓인 무늬들과는 너무나 대조적이다. 그러나 우리가 마주보게 되는 건 언제나 그 후면이 아닌 전면일 뿐이다.

김진희는 개개인의 과거에 대한 기억과 상처 그리고 어떤 수치스런 감정을 덮어주는 방법으로 바느질을 시작했다고 고백한다. 그리고 여성의 나체 일부를 가리워 그들의 익명성을 보장하려던 첫 의도와는 다르게, 작가는 실을 꿰매고 그들의 이야기를 되뇌이는 과정에서 상실의 기억과 치유는 완전히 회복될 수 없는 어떤 것임을 깨닫는다. 여기 또 다른 시리즈, 진도를 배경으로 한 [에이프릴]을 보자. 에이프릴은 새로운 시작과 희망을 알리는 계절을 뜻한다. 그러나 이제 4월은 우리에게 슬픔과 고통이 짙게 깔린 날로 기억된다. 아니, 이젠 잊혀질 수 없는 상처의 계절이 되어버렸다. 그녀의 사진에 ‘잊지 않겠습니다’라는 글귀는 없지만 노란색 무늬들로 수놓인 사진 속 풍경은 왠지 모를 평화로움에 애잔함이 더해졌다. 과연 누군가의 기억을 보듬고 그 상처를 치유한다는 건 가능한가? 프로이트는 기억과 트라우마, 멜랑콜리아에 관하여 우리가 가까운 이의 죽음이나 국가적 위기 같은 ‘비극’ 또는 ‘상실’을 경험했을 때 과거의 기억을 무의식적으로 거부하게 된다고 했다. 그 이유는 그 트라우마가 주체의 존재 자체를 위협할 만큼 치명적이기 때문이며 그 주체를 보호하기 위해서는 표면화되는 것을 억압한다는 것이다. 프로이트가 말하는 상실의 공포와 불안을 잠식시키는 것, 이를 김진희는 현실의 생생한 기록이 아닌 그 상처의 표면을 덮는 것으로 대신한다. 현실의 비참함을 목도하기 보다는, 약속을 대신한 기억의 무늬들을 채워 가면서 말이다. 어떤 면에서 치유는 기억을 탈색시키는 과정인지도 모른다.

사진과 글, 여기에 바느질이란 방법을 빌린 김진희의 두 번째 시리즈 [She]는 이제 좀 더 절제되고 상징적인 이미지를 통해 세상을 바라보려 한다. 복잡 미묘한 여성의 눈으로 기록한 ‘이름 없는 성, 그녀’ 그리고 또 다른 상처의 기억들. 우리는 김진희가 이미지를 통해 전달하고자 하는 것이 성(gender)의 본질에 대한 탐구가 아니라 다만 서로 다른 기억과 의미들을 끊임없이 생산해가며 이루어지는 공감에 있음을 추측할 뿐이다. 그리고 이렇게 실을 연결 짓고 매듭짓는 행위는 이름 없는 것들에 의미를 다시 새겨 넣는 일과 다름 아닌지도 모른다.

IANN 예술사진잡지 편집장 김정은

1)할 포스터 Hal Foster 외,『 1900년 이후의 미술사: 모더니즘, 반모더니즘, 포스트모더니즘 Art since 1900: modernism, antimodernism, postmodernism』, (Thames & Hudson, 2004) 배수희 외 옮김(세미콜론, 2012), p626

2)우정아, 『상실과 우울, 트라우마로 읽는 현대 미술 I』, 경향 아티클 (20호, 2013년 3월), p.54-57

“시시한 것 같아 보여도 어느 날은 그게 또 전혀 아니니까. 나를 납득시키기 위해 수많은 문장들을 고쳤다 쓰고 위에 덧대어야 한다. 터져 나오는 웃음은 너무나 치사해, 싫어,”

“정말은 밤길이 무서웠던게 아니었어요. 나를 잊어버리고 가는게 무서웠어요. 그래도 역시 나는 잊혀졌어요. 말을 했지만. 나는 너무나도 가벼웠나봐요. 그렇게 쉽게 잊고, 쉽게 말하는, 말을 했지만”

[’She’ 시리즈 중, 일부 대화글 발췌]

현대미술에서 여성이라는 주제는 가부장적인 제도의 구조적 모순을 인지하고 남성 중심의 문화에 도전하는 방식에서 1970년대 전후 미국 페미니스트들을 중심으로 확산되었다. 이전까지 성적인 억압으로 소외되었던 여성의 신체는 여성이 바라보는 성(gender/sexuality)에 대한 인식을 탐구하는 주된 소재가 되었으며 그들의 비평적 태도는 역사적으로 저평가된 여성의 가사 노동인 바느질, 장식미술, 실용 공예 등을 미술 안으로 수용시키는데 일조한다. 이러한 초기 페미니즘 미술은 신체미술, 퍼포먼스, 설치미술 등으로 대부분 급진적이고 직설적인 화법이 주를 이뤘다. 그리고 80년대 중반부터는 매스 미디어, 영화 같은 공적 이미지에 투영된 여성상을 차용하거나 전복시키는 방식으로 발전하기에 이른다. 그 대표적인 예로서, 우리는 로라 멀비의 [시각적 쾌락과 서사영화], 신디 셔먼의 [무제 영화 스틸], 대중매체를 원천으로 하는 사진들을 차용한 바바라 크루거의 작품들을 떠올릴 수 있다. 물론 현재에도 여성의 이미지와 여성에 의한 이미지를 복권하기 위한 시도들은 여러 예술가들을 통해 보여지고 있다. 그러나 수십년의 시간 동안 우리는 여성 예술가의 작업들이 단순한 논리와 형태로만 존재하지 않으며 따라서 이제 이런 모든 시도들을 페미니즘 미술로 단정짓기도 어려워졌다.

이제 갓 서른이 된 김진희는 20대의 한국 여성을 카메라에 꾸준히 담아왔다. 그리고 이번 전시를 통해 그녀는 풋풋한 20대의 첫 경험이나 여성의 성적 욕망에서 한걸음 더 나아가 그(녀)들의 과거에 대한 기억, 상처, 트라우마를 진지하게 바라보려 한다. 김진희의 신작 [She]에는 9명의 인물사진에 촘촘히 박힌 제목들이 먼저 눈에 띈다. 잡지 커버나 광고 문구처럼 이 텍스트는 무언의 메시지를 강렬히 던지지만 우리는 좀처럼 그 의미를 쉽게 이해하기 힘들다. 다만 김진희가 이들과 나눈 짧은 대화나 편지를 바탕으로 우리는 이 모호한 텍스트가 어디서 출몰한 것인지 짐작할 따름이다. 이런 김진희의 사진이 유독 흥미로운 건, 그들의 몸짓과 언어가 섞인 사진 텍스트로 인해 여성 특유의 섬세한 감성과 심리가 독특하게 표현되었기 때문이다. 여기서 텍스트는 시인의 언어처럼 눈앞의 대상을 묘사하는 것이 아니라 여성의 관념을 자극하는 특수한 시각언어로 자리한다. 이와 유사하게 우리는 여성에 대한 통념을 불식시키는 방법으로 사진과 텍스트를 조합해 온 작가로 바바라 크루거를 연관시켜 볼 법하다. 크루거의 [우리는 당신의 문화에 대해 자연이 되지 않겠다. We won’t Play Nature to Your Culture](1983)는 나뭇잎으로 눈을 가린 채 일광욕을 하는 젊은 여성의 사진 위에 문장을 적는 식으로 남성/여성의 대립만큼이나 뿌리 깊은 자연/문화의 대립을 시각화 시켜왔다. 그녀의 다소 냉소적이며 직설적인 문구는 그 당시 미국 사회에 뿌리 깊게 박혀있는 성차와 고정관념을 타파하는 방법이었던 것이다. 이는 “즉 남성이 행위자일 때 여성은 수동적인 대상이고, 남성이 의미의 발화자이자 제작자인 반면, 발화의 대상인 여성은 의미의 담지자에 불과하다”라는 시각의 성적 역학 관계, 즉 “이전까지 젊은 여성은 시각의 대상이지 주체가 아니다” 임을 알려준다.

그렇다면 이미지와 텍스트를 상이하게 충돌시키는 방법을 통해 김진희가 보여주고자 하는 것은 무엇일까? 크루거의 사진 텍스트가 선언적인 광고와 같다면 김진희의 작업은 명증적인 것을 거부하는 문학이나 시를 닮았다. 이 시리즈에 등장하는 젊은 여성들은 시각적 욕망의 대상이면서 동시에 발언하는 주체이다. 그러나 작가는 그녀들이 나눈 솔직한 대화들을 짧은 몇 줄의 문구로 축소시키고 다시 여러 언어로 번역하면서 본연의 메시지를 가리거나 숨겨버린다. 김진희의 첫 시리즈인 [속삭임/속삭이기whisper/ing (2009-2013)] 처럼, 그녀들의 대화는 여기서도 완전히 발화되지 못한 웅얼거림과 같다. 또한 이 시리즈 제목인 삼인칭 대명사 ‘She’는 ‘조용히 해’라는 감탄사 ‘쉬~’를 떠올리게도 한다. 당혹스럽지만 은밀하고, 명료하지만 충분히 설명되지 않는 뉘앙스. 여기에 그녀들이 던지는 강렬한 응시는 ‘모든 걸 설명하지 않아도 이해해줘’라는 제스처로 우리를, 아니 그들을 당혹스럽게 만든다. ‘역시 알다가도 모르는 게 여자야’라는 남자들의 푸념을 떠올리게 되는 건 이제껏 여성이 취한 대화 방식이 이렇듯이 절제되고 상징적이기 때문일 것이다. 바로 이 지점에서 여성은 말초적 쾌락에 순응하는 대상이 아닌 ‘이름 없는 타자’로서 등장하고 있음을 알 수 있다. 그리고 우리는 이 시리즈의 여성(=She)이 어느 쪽으로도 예속되지 못하는 의미의 발화자이자 동시에 담지자임을 눈여겨 볼 필요가 있다.

앞서 언급한 것처럼 김진희의 미완인 텍스트와 기하학적 패턴들은 감성적, 심리적 상황을 연출하지만 이는 언제나 모순적으로 드러난다. 그리고 이러한 모호함(웅얼거림 같은)은 수차례 반복적으로 실로 꿰매는 작업과정을 통해 여실히 드러난다. 주지하다시피 장시간 되풀이 한 바느질은 통상적으로 몇 장의 사진을 얻기 위해 촬영했던 작가의 예전 경험과는 사뭇 다르다. 마치 여러 번 문장을 쓰고 고치듯이 사진 표면에 실로 덧대는 반복적인 행위는 긴 노동의 시간을 필요로 하며 이로 인하여 그들이 토로한 비밀스런 기억들을 들추고 감추어야 하는 책임은 오롯이 김진희의 몫일 수 밖에 없다. 그리고 역설적이게도 그녀들의 이야기(또는 목소리)를 실로 입히는 이 지난한 과정은 필연적으로 사진 원본을 파손시키면서 거듭난다. 누군가의 상처를 덧대어 치유하는 행위가 반대로는 본인의 사진에 상처를 입히고 마는 것이다. 엉기성기 거칠게 박힌 사진의 뒷면은 그 앞면에 고이 수놓인 무늬들과는 너무나 대조적이다. 그러나 우리가 마주보게 되는 건 언제나 그 후면이 아닌 전면일 뿐이다.

김진희는 개개인의 과거에 대한 기억과 상처 그리고 어떤 수치스런 감정을 덮어주는 방법으로 바느질을 시작했다고 고백한다. 그리고 여성의 나체 일부를 가리워 그들의 익명성을 보장하려던 첫 의도와는 다르게, 작가는 실을 꿰매고 그들의 이야기를 되뇌이는 과정에서 상실의 기억과 치유는 완전히 회복될 수 없는 어떤 것임을 깨닫는다. 여기 또 다른 시리즈, 진도를 배경으로 한 [에이프릴]을 보자. 에이프릴은 새로운 시작과 희망을 알리는 계절을 뜻한다. 그러나 이제 4월은 우리에게 슬픔과 고통이 짙게 깔린 날로 기억된다. 아니, 이젠 잊혀질 수 없는 상처의 계절이 되어버렸다. 그녀의 사진에 ‘잊지 않겠습니다’라는 글귀는 없지만 노란색 무늬들로 수놓인 사진 속 풍경은 왠지 모를 평화로움에 애잔함이 더해졌다. 과연 누군가의 기억을 보듬고 그 상처를 치유한다는 건 가능한가? 프로이트는 기억과 트라우마, 멜랑콜리아에 관하여 우리가 가까운 이의 죽음이나 국가적 위기 같은 ‘비극’ 또는 ‘상실’을 경험했을 때 과거의 기억을 무의식적으로 거부하게 된다고 했다. 그 이유는 그 트라우마가 주체의 존재 자체를 위협할 만큼 치명적이기 때문이며 그 주체를 보호하기 위해서는 표면화되는 것을 억압한다는 것이다. 프로이트가 말하는 상실의 공포와 불안을 잠식시키는 것, 이를 김진희는 현실의 생생한 기록이 아닌 그 상처의 표면을 덮는 것으로 대신한다. 현실의 비참함을 목도하기 보다는, 약속을 대신한 기억의 무늬들을 채워 가면서 말이다. 어떤 면에서 치유는 기억을 탈색시키는 과정인지도 모른다.

사진과 글, 여기에 바느질이란 방법을 빌린 김진희의 두 번째 시리즈 [She]는 이제 좀 더 절제되고 상징적인 이미지를 통해 세상을 바라보려 한다. 복잡 미묘한 여성의 눈으로 기록한 ‘이름 없는 성, 그녀’ 그리고 또 다른 상처의 기억들. 우리는 김진희가 이미지를 통해 전달하고자 하는 것이 성(gender)의 본질에 대한 탐구가 아니라 다만 서로 다른 기억과 의미들을 끊임없이 생산해가며 이루어지는 공감에 있음을 추측할 뿐이다. 그리고 이렇게 실을 연결 짓고 매듭짓는 행위는 이름 없는 것들에 의미를 다시 새겨 넣는 일과 다름 아닌지도 모른다.

IANN 예술사진잡지 편집장 김정은

1)할 포스터 Hal Foster 외,『 1900년 이후의 미술사: 모더니즘, 반모더니즘, 포스트모더니즘 Art since 1900: modernism, antimodernism, postmodernism』, (Thames & Hudson, 2004) 배수희 외 옮김(세미콜론, 2012), p626

2)우정아, 『상실과 우울, 트라우마로 읽는 현대 미술 I』, 경향 아티클 (20호, 2013년 3월), p.54-57

A Nameless Woman, She

“Even though it seems pitiful and boring on one day, on another day this may no longer be the case. I need to fix and rewrite numerous sentences and add to them in order to persuade myself. To burst out laughing is too shameful, I don’t like it.”

“I wasn’t scared of walking at night. What’s frightening was to forget myself. I was forgotten. I spoke many times, but maybe what I said was too trivial. I was easily forgotten and gossiped about, though I spoke many times.”

She series, excerpt of a conversation

The theme of woman in the contemporary art world was broached in the 1970s by feminists in the United States in ways that they recognized the structural contradictions of patriarchal systems and challenged the male-dominated culture. The female body, which had been alienated due to sexual repression, surfaced as a major subject matter in exploring awareness towards gender/sexuality as perceived by women. Their critical attitude helped incorporate the female body into the realms of art, decorative art, crafts, and even sewing, which was once denigrated as a female domestic labor. These early feminist arts, such as performance, installation, and body art, were mostly based on radical discourses and relatively straightforward speech. Since the mid-1980s, the feminist arts have developed into a way that appropriated or subverted the female images that were publicly represented in the mass media, such as film. For example, Laura Mulvey’s Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, and Barbara Kruger’s use of image and text that drew upon mass media. Even now such attempts are done by many artists in an effort to rehabilitate women’s self-perceptions. However, it is difficult to conclusively state that all those works can be considered as part of the feminist art movement, as for decades it has not worked on simple logic and forms.

JinHee Kim, who has just turned thirty, has unflaggingly taken pictures of Korean women in their twenties. In this exhibition, Kim shows us honest perspectives about her subject’s memories, wounds, and trauma. By going one step beyond her previous subject matter, such as the first sexual experiences and desires of women in their twenties, Kim now densely embedded titles with the nine portraits. The texts signify implicit messages, as if they were taken out of magazine covers or advertisements; however, these meanings are barely intelligible. Just a slight hint is given through the letters or short talks that are shared between Kim and the other women, from whom these ambiguous texts come from. The reason why Kim’s photos are particularly whimsical lies in the way that they reveal a certain kind of subtle sensitivity and psychology, which belong only to women, in the combining of body gestures with text. The text in this context serves as another type of visual language that facilitates female perception. In combining image and text to challenge and subvert the fixed notions of woman, Kim’s work may be related to that of Kruger’s. We Won’t Play Nature to Your Culture (1983), one of Kruger’s most representative works, instantiates the confrontation between the natural and the cultural as deeply rooted as a conflict between man and woman, as she wrote the eponymous title on a photograph of a young woman sunbathing with her both eyes hidden with leaves. Kruger’s skeptical and straightforward texts are used as a way to break down the prevalent sexual discrimination and prejudice deeply rooted in American society. This exemplifies a gender dynamic that “men act while women are acted upon, and men are speakers and producers of meaning, while women are no more than holders of meaning as objects of speaking, and until then, young women had been objects of seeing, far from being subjects.”

What does Kim intend to present through her way in juxtaposing image and text, which are in conflict with one another? Kim’s phrases resemble literary texts, such as poems that refuse to be transparently univocal, while Kruger’s work is suggestive of mainstream advertisements. The young women appearing in this series act as both objects of visual desire and subjects having a voice. However, Kim simplifies the sincere talk into just a few phrases, and translates them into different languages, in order to hide the original messages. As in Kim’s first series Whispering (2009-2013), the conversation among women seems like mumbling that is yet to be articulated. In addition, the title of Kim’s work, She (also a third person pronoun), is phonetically similar to an exclamation, “sh,” as in telling someone to be quiet. It evokes certain emotive feelings that are embarrassing yet secretive, and are also clear yet not fully explicable. The intense gazes projected by the women might be embarrassing to viewers, and even to themselves, as if saying, “We do not want to explain, but please just understand us.” Such a symbolic and shorthand way of speaking by women quite possibly leads men to conclude, “women are totally unpredictable.” This is the point where the women in the She series appear as the “Other with no name,” instead of remaining as objects who comply with (men’s) trivial pleasures. Therefore, attention should be drawn to the fact that the women in the She belong both to speakers and holders of meaning without being characterized as one or the other.

As previously mentioned, Kim’s incomplete text and geometric patterns on the images evoke emotional and psychological empathy as they contradict one another. In addition, such incoherency and vagueness is often repetitively found in the process of sewing with threads. The hours-long sewing is allegedly quite different from Kim’s previous experience in working with the camera to obtain a few photographs. The repetitive behavior, in sewing the surface of photographs requires long tedious laborious efforts and somehow became Kim’s responsibility to determine which memories are to be hidden and which ones are to be exposed. Paradoxically speaking, their memories changed anew as Kim’s act of sewing and “healing” brings about unexpected effects in “damaging” the original prints. The backside of the photograph reveals entangled traces of the threads, which are a deep contrast to the exquisitely embroidered patterns on its front side. However, it is only the front side that the viewer is able to view.

Kim states that she began sewing to cure the wounds of past unpleasant memories and shameful emotions belonging to her subjects. Unlike the initial attempts to guarantee their anonymity by covering parts of the women's naked bodies, while sewing with echoes of their narratives, Kim is doubtful whether their wounds are curable. Also included in this exhibition is another series titles April, which is based on the Jindo incident on April 16, 2014. In general, April is a herald of spring, signifying a new beginning and inspiring hope. However, this past April has become emblematic of deep sorrow and pain in Korea. Since the South Korean Sewol ferry disaster, April has turned into a time of the year when Koreans are bound to be reminded of that tragic accident. Even without the phrase, “We won’t forget!” that is inscribed on Kim’s photo, the yellow dots shattered all over the surface leave one with feelings of a peaceful but plaintive sadness. The pale hues convey some wish of healing the wounds in the still heartrending memories. Is it possible to relive someone’s memory and heal the wounds? As for memory, trauma, and melancholia, Freud argued that an experience of tragedy or loss (such as a death of a loved one or a national disaster) makes a person unconsciously deny memories from the past; trauma is of such a critical nature as to threaten one’s own existence, therefore it is often repressed from coming into the consciousness, in order to protect oneself. Referring to Freud’s repression of the pain and anxiety in the mind, Kim tries to ameliorate the wounds of others by sewing as a way to deal with the loss, fear, and uneasiness, instead of just reporting the reality. Kim weaves patterns that are drawn from memories, rather than merely making unkempt promises, or witnessing the tragedy of the reality. In a sense, healing might be none other than a bleaching of memory.

Kim’s second series, She, uses the image, text, and sewing, and thereby reflects her perspective on the world in moderate and symbolic ways. As a visual reportage from a woman’s sensitive and subtle view towards wounded memories, Kim hopes that her work is a way in which she can keep establishing a kind of contact with women, rather than conceptualizing the gender issue or power roles as a feminist. The act of sewing threads and tying knots may be to weave new meanings in the memories that have lost their names.

Contemporary Art Photography Magazine IANN

Jeong Eun Kim, Chief Editor

1) Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, et al., Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism, Thames & Hudson, 2004, p. 626.

2) The sinking of the Sewol ferry occurred on the morning of April 16, 2014, near the Jindo port. The South Korean ferry capsized with 476 people on-board, mostly secondary school students. In all, 304 passengers died in the disaster and that resulted in widespread social and political reaction in South Korea.

3) Woo Jeong-a, “Contemporary Art I: Reading through Loss, Depression, and Trauma,” Gyeonghyang Article (No. 20, March 2013) pp. 54-57.

“Even though it seems pitiful and boring on one day, on another day this may no longer be the case. I need to fix and rewrite numerous sentences and add to them in order to persuade myself. To burst out laughing is too shameful, I don’t like it.”

“I wasn’t scared of walking at night. What’s frightening was to forget myself. I was forgotten. I spoke many times, but maybe what I said was too trivial. I was easily forgotten and gossiped about, though I spoke many times.”

She series, excerpt of a conversation

The theme of woman in the contemporary art world was broached in the 1970s by feminists in the United States in ways that they recognized the structural contradictions of patriarchal systems and challenged the male-dominated culture. The female body, which had been alienated due to sexual repression, surfaced as a major subject matter in exploring awareness towards gender/sexuality as perceived by women. Their critical attitude helped incorporate the female body into the realms of art, decorative art, crafts, and even sewing, which was once denigrated as a female domestic labor. These early feminist arts, such as performance, installation, and body art, were mostly based on radical discourses and relatively straightforward speech. Since the mid-1980s, the feminist arts have developed into a way that appropriated or subverted the female images that were publicly represented in the mass media, such as film. For example, Laura Mulvey’s Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, and Barbara Kruger’s use of image and text that drew upon mass media. Even now such attempts are done by many artists in an effort to rehabilitate women’s self-perceptions. However, it is difficult to conclusively state that all those works can be considered as part of the feminist art movement, as for decades it has not worked on simple logic and forms.

JinHee Kim, who has just turned thirty, has unflaggingly taken pictures of Korean women in their twenties. In this exhibition, Kim shows us honest perspectives about her subject’s memories, wounds, and trauma. By going one step beyond her previous subject matter, such as the first sexual experiences and desires of women in their twenties, Kim now densely embedded titles with the nine portraits. The texts signify implicit messages, as if they were taken out of magazine covers or advertisements; however, these meanings are barely intelligible. Just a slight hint is given through the letters or short talks that are shared between Kim and the other women, from whom these ambiguous texts come from. The reason why Kim’s photos are particularly whimsical lies in the way that they reveal a certain kind of subtle sensitivity and psychology, which belong only to women, in the combining of body gestures with text. The text in this context serves as another type of visual language that facilitates female perception. In combining image and text to challenge and subvert the fixed notions of woman, Kim’s work may be related to that of Kruger’s. We Won’t Play Nature to Your Culture (1983), one of Kruger’s most representative works, instantiates the confrontation between the natural and the cultural as deeply rooted as a conflict between man and woman, as she wrote the eponymous title on a photograph of a young woman sunbathing with her both eyes hidden with leaves. Kruger’s skeptical and straightforward texts are used as a way to break down the prevalent sexual discrimination and prejudice deeply rooted in American society. This exemplifies a gender dynamic that “men act while women are acted upon, and men are speakers and producers of meaning, while women are no more than holders of meaning as objects of speaking, and until then, young women had been objects of seeing, far from being subjects.”

What does Kim intend to present through her way in juxtaposing image and text, which are in conflict with one another? Kim’s phrases resemble literary texts, such as poems that refuse to be transparently univocal, while Kruger’s work is suggestive of mainstream advertisements. The young women appearing in this series act as both objects of visual desire and subjects having a voice. However, Kim simplifies the sincere talk into just a few phrases, and translates them into different languages, in order to hide the original messages. As in Kim’s first series Whispering (2009-2013), the conversation among women seems like mumbling that is yet to be articulated. In addition, the title of Kim’s work, She (also a third person pronoun), is phonetically similar to an exclamation, “sh,” as in telling someone to be quiet. It evokes certain emotive feelings that are embarrassing yet secretive, and are also clear yet not fully explicable. The intense gazes projected by the women might be embarrassing to viewers, and even to themselves, as if saying, “We do not want to explain, but please just understand us.” Such a symbolic and shorthand way of speaking by women quite possibly leads men to conclude, “women are totally unpredictable.” This is the point where the women in the She series appear as the “Other with no name,” instead of remaining as objects who comply with (men’s) trivial pleasures. Therefore, attention should be drawn to the fact that the women in the She belong both to speakers and holders of meaning without being characterized as one or the other.

As previously mentioned, Kim’s incomplete text and geometric patterns on the images evoke emotional and psychological empathy as they contradict one another. In addition, such incoherency and vagueness is often repetitively found in the process of sewing with threads. The hours-long sewing is allegedly quite different from Kim’s previous experience in working with the camera to obtain a few photographs. The repetitive behavior, in sewing the surface of photographs requires long tedious laborious efforts and somehow became Kim’s responsibility to determine which memories are to be hidden and which ones are to be exposed. Paradoxically speaking, their memories changed anew as Kim’s act of sewing and “healing” brings about unexpected effects in “damaging” the original prints. The backside of the photograph reveals entangled traces of the threads, which are a deep contrast to the exquisitely embroidered patterns on its front side. However, it is only the front side that the viewer is able to view.

Kim states that she began sewing to cure the wounds of past unpleasant memories and shameful emotions belonging to her subjects. Unlike the initial attempts to guarantee their anonymity by covering parts of the women's naked bodies, while sewing with echoes of their narratives, Kim is doubtful whether their wounds are curable. Also included in this exhibition is another series titles April, which is based on the Jindo incident on April 16, 2014. In general, April is a herald of spring, signifying a new beginning and inspiring hope. However, this past April has become emblematic of deep sorrow and pain in Korea. Since the South Korean Sewol ferry disaster, April has turned into a time of the year when Koreans are bound to be reminded of that tragic accident. Even without the phrase, “We won’t forget!” that is inscribed on Kim’s photo, the yellow dots shattered all over the surface leave one with feelings of a peaceful but plaintive sadness. The pale hues convey some wish of healing the wounds in the still heartrending memories. Is it possible to relive someone’s memory and heal the wounds? As for memory, trauma, and melancholia, Freud argued that an experience of tragedy or loss (such as a death of a loved one or a national disaster) makes a person unconsciously deny memories from the past; trauma is of such a critical nature as to threaten one’s own existence, therefore it is often repressed from coming into the consciousness, in order to protect oneself. Referring to Freud’s repression of the pain and anxiety in the mind, Kim tries to ameliorate the wounds of others by sewing as a way to deal with the loss, fear, and uneasiness, instead of just reporting the reality. Kim weaves patterns that are drawn from memories, rather than merely making unkempt promises, or witnessing the tragedy of the reality. In a sense, healing might be none other than a bleaching of memory.

Kim’s second series, She, uses the image, text, and sewing, and thereby reflects her perspective on the world in moderate and symbolic ways. As a visual reportage from a woman’s sensitive and subtle view towards wounded memories, Kim hopes that her work is a way in which she can keep establishing a kind of contact with women, rather than conceptualizing the gender issue or power roles as a feminist. The act of sewing threads and tying knots may be to weave new meanings in the memories that have lost their names.

Contemporary Art Photography Magazine IANN

Jeong Eun Kim, Chief Editor

1) Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, et al., Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism, Thames & Hudson, 2004, p. 626.

2) The sinking of the Sewol ferry occurred on the morning of April 16, 2014, near the Jindo port. The South Korean ferry capsized with 476 people on-board, mostly secondary school students. In all, 304 passengers died in the disaster and that resulted in widespread social and political reaction in South Korea.

3) Woo Jeong-a, “Contemporary Art I: Reading through Loss, Depression, and Trauma,” Gyeonghyang Article (No. 20, March 2013) pp. 54-57.

김진희 Kim, Jin-Hee

1985 부산 출생

.........현재 서울에서 거주 및 활동

학력

2008 중앙대학교 사진학과 졸업

개인전

2014 이름 없는 여성, She, 송은 아트큐브, 서울

2012 Whisper(ing), 트렁크 갤러리, 서울

.........Whisper(ing), Place M Gallery, 도쿄, 일본

2007 In whispers, 갤러리 바-로베르네, 서울

그룹전

2014 Young Portfolio Acquisitions 2013, 기요사토 사진 미술관, 기요사토, 일본

2013 뉴어반스케이프, 전주포토페스티벌, 갤러리 옵센, 전주

.........이어지다_succeeding, 사진비평상 역대 수상자전, 이앙갤러리, 서울

2011 청년미술프로젝트 포트폴리오 도큐멘터, EXCO, 대구

.........제12회 사진비평상 수상자전, 이룸 갤러리, 서울

2009 국제사진교류전, 울산아트센터, 울산

2008 "오늘날의 동화" 서안미술대전, 서안예술학교, 서안, 중국

2007 Tempering, 아트센터보다, 서울

2006 Tempering, 몽상스튜디오, 서울

수상 및 간행물

2011 제12회 사진비평상, 아이포스, 서울

2010 Whisper(ing), 이안북스, 서울

소장

기요사토 사진 미술관

1985 부산 출생

.........현재 서울에서 거주 및 활동

학력

2008 중앙대학교 사진학과 졸업

개인전

2014 이름 없는 여성, She, 송은 아트큐브, 서울

2012 Whisper(ing), 트렁크 갤러리, 서울

.........Whisper(ing), Place M Gallery, 도쿄, 일본

2007 In whispers, 갤러리 바-로베르네, 서울

그룹전

2014 Young Portfolio Acquisitions 2013, 기요사토 사진 미술관, 기요사토, 일본

2013 뉴어반스케이프, 전주포토페스티벌, 갤러리 옵센, 전주

.........이어지다_succeeding, 사진비평상 역대 수상자전, 이앙갤러리, 서울

2011 청년미술프로젝트 포트폴리오 도큐멘터, EXCO, 대구

.........제12회 사진비평상 수상자전, 이룸 갤러리, 서울

2009 국제사진교류전, 울산아트센터, 울산

2008 "오늘날의 동화" 서안미술대전, 서안예술학교, 서안, 중국

2007 Tempering, 아트센터보다, 서울

2006 Tempering, 몽상스튜디오, 서울

수상 및 간행물

2011 제12회 사진비평상, 아이포스, 서울

2010 Whisper(ing), 이안북스, 서울

소장

기요사토 사진 미술관

Kim, Jin-Hee

1985 Born in Busan, Korea

.........Lives and works in Seoul, Korea

Education

2008 B.F.A. Chung-Ang University, Photography, Seoul, Korea

Solo Exhibitions

2014 A Nameless Woman, She, SongEun ArtCube, Seoul, Korea

2012 Whisper(ing), Trunk Gallery, Seoul, Korea

.........Whisper(ing), Place M Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

2007 In whispers, Gallery bar-chez robert, Seoul, Korea

Group Exhibitions

2014 Young Portfolio Acquisitions 2013, Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts, Kiyosato, Japan

2013 New Urban Scape, Jeonju Photo Festival, Jeonju, Korea

.........Succeeding, Iang gallery, Seoul, Korea

2011 Young Artists Project: portfolio documenta, EXCO, Taegu, Korea

.........The 12th Sajin Bipyong Award Artists Exhibition, Gallery Illum, Seoul, Korea

2009 National Photographic Exchange Invitation Exhibition, Ulsan Art Center, Ulsan, Korea

2008 2008 Fairy tale of the Day, Xian Art School, Xian, China

2007 Tempering, Art Center of Photography BODA, Seoul, Korea

2006 Tempering, Mongsang Studio, Seoul, Korea

Award and Publication

2011 The 12th Sajin Bipyong Award, IPHOS, Seoul, Korea

2010 Whisper(ing), IANNBOOKS, Seoul, Korea

Collections

Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts

1985 Born in Busan, Korea

.........Lives and works in Seoul, Korea

Education

2008 B.F.A. Chung-Ang University, Photography, Seoul, Korea

Solo Exhibitions

2014 A Nameless Woman, She, SongEun ArtCube, Seoul, Korea

2012 Whisper(ing), Trunk Gallery, Seoul, Korea

.........Whisper(ing), Place M Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

2007 In whispers, Gallery bar-chez robert, Seoul, Korea

Group Exhibitions

2014 Young Portfolio Acquisitions 2013, Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts, Kiyosato, Japan

2013 New Urban Scape, Jeonju Photo Festival, Jeonju, Korea

.........Succeeding, Iang gallery, Seoul, Korea

2011 Young Artists Project: portfolio documenta, EXCO, Taegu, Korea

.........The 12th Sajin Bipyong Award Artists Exhibition, Gallery Illum, Seoul, Korea

2009 National Photographic Exchange Invitation Exhibition, Ulsan Art Center, Ulsan, Korea

2008 2008 Fairy tale of the Day, Xian Art School, Xian, China

2007 Tempering, Art Center of Photography BODA, Seoul, Korea

2006 Tempering, Mongsang Studio, Seoul, Korea

Award and Publication

2011 The 12th Sajin Bipyong Award, IPHOS, Seoul, Korea

2010 Whisper(ing), IANNBOOKS, Seoul, Korea

Collections

Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts