Planet Guantánamo

Homo sacer is a legal status defined by ancient Roman law. Despite its original definition of 'sacred man', a homo sacer could be killed anytime, and nobody would be punished for this murder. Even so, they were deemed unqualified as religious sacrifice as they were thought to be too filthy and distasteful to touch, cursed and despised, far from sacred. At the time, the lives of homo sacer were meaningless, their humanity denied by all. The term came to life again when Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben used it to explain brutality of modern nations.

While Foucault suggested that the mechanism of the modern nation enhancing power and discriminating among its people is justified by its desire to control child birth and disease, Agamben takes a step further and criticizes the modern nation for violently exploiting life itself for the sake of national interest. To Agamben, Guantánamo Bay in particular is the most evident 'extraterritorial' location for contemporary homo sacer. As the U.S.-claimed “War on Terror” after the 9.11 attack, civilians suspected of being “enemy combatants” were imprisoned in Guantánamo Bay without charge or trial. In the power game of international politics, America’s mere suspicion of these men silenced any opposing voices. The way America created homo sacer was tolerated and even justified by asserting that because terrorism is itself outside the law, it deserves be punished in kind.

Suspected terrorists around the world were arrested and brought to the U.S. Naval Station in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, or GTMO (pronounced “Gitmo”). Because, in the eyes of the U.S. government, Guantánamo is not a “prison” but a “detention center,” its inmates not “prisoners” but “enemy combatants” or “unprivileged belligerents,” Geneva Convention protections for prisoners of war do not apply. U.S. constitutional protections do not apply either because the military base stands on Cuban soil. The location was chosen explicitly to allow for indefinite detention and torturous interrogation, beyond the reach of the law. The place is like an extraterritorial planet, functioning as an entirely different world. The inmates at Guantánamo have no power except over their own bodies. Many have engaged in long-term hunger strikes to protest their indefinite detention. Yet they are stripped even of this right, reframed by the military as “long-term non-religious fasts,” as they are force-fed through a tube, a process referred to as “enteral feeding.”

2015년 1월 개관한 BMW Photo Space는 부산, 영남지역 BMW MINI 공식 딜러 동성 모터스와 고은문화재단, 고은사진미술관이 함께 운영하는 사진 전시 공간이다.

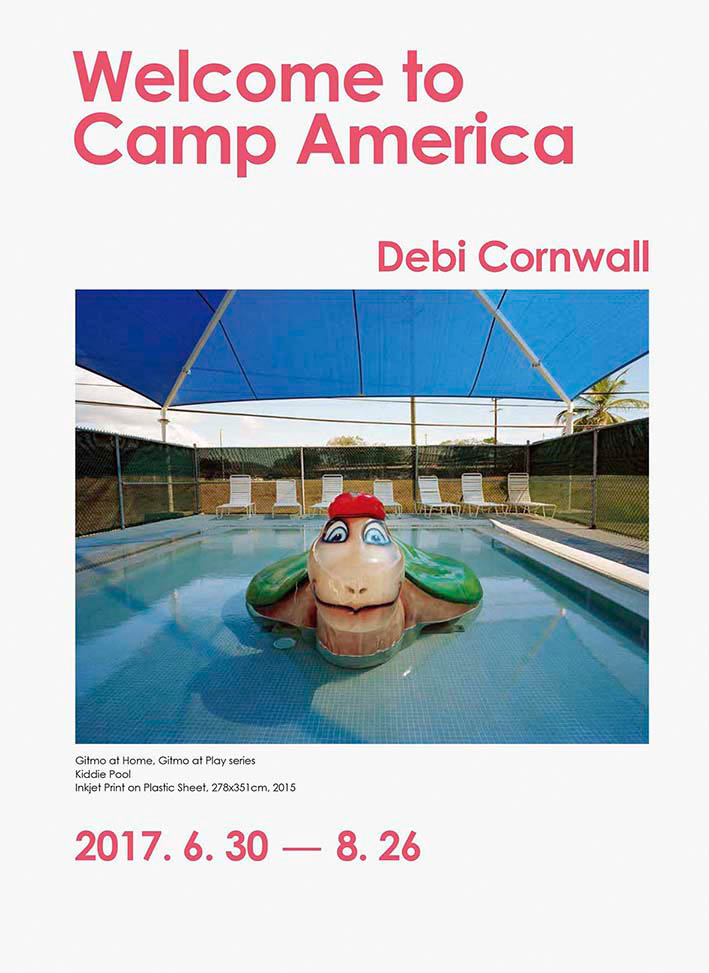

부산 해운대에 위치한 이 공간은 ‘청사진 신진작가 지원 프로젝트’, ‘해외 신진작가 교류전’을 중심으로 한국의 신진작가를 발굴·지원하고 해외의 주목할 만한 경향을 소개하고 있다. 그 중 ‘해외 신진작가 교류전’은 동시대 다른 문화권 작가들의 작업을 선보임으로써 한국 사진의 위치를 확인하고 발전을 모색하기 위한 기획전이기도 하다. 2015년 첫 번째 해외 신진작가 교류전에서는 일본의 Kura Masumi를 선보였다. 2017년에는 두 번째 해외신진작가 교류전으로 미국 작가 Debi Cornwall의 《Welcome to Camp America》를 선보인다. Debi Cornwall은 2015년부터 고은사진미술관과 꾸준한 교류를 이어온 미국 휴스턴의 포토페스트를 통해 선정된 작가이다.

고은사진미술관 ∙ BMW Photo Space

고은사진미술관 ∙ BMW Photo Space

호모 사케르를 위하여

행성, 관타나모

고대 로마법이 정한 호모사케르가 있다. 신성한 인간이라는 원래 뜻과 달리 그들은 언제든 죽임을 당할 수 있었고, 그들을 죽인다 해서 누구 하나 처벌받지 않았다. 그런데도 신의 제물로 바쳐질 자격은 안 되는 사람들. 사케르란 만지기에 더럽고 추한, 신성함과는 거리가 먼 저주와 경멸의 대상이었다. 당시 호모사케르는 목숨이 어찌되건 아무도 신경 쓰지 않는 존재 밖의 사람들이었다. 이탈리아 사상가 조르조 아감벤은 현대 국가의 폭력성을 설명하기 위해 이 호모사케르 개념을 부활시킨다.

출산과 질병 등의 관리를 명분으로 생명에 관한 통제와 차별을 강화한 근대 국가의 속성을 푸코가 제시했다면, 아감벤은 한발 더 나아가 국가의 이익을 위해 생명 자체를 수단으로 삼는 현대 국가의 교활함을 고발한다. 특히 관타나모 미군 기지는 현대판 호모사케르가 존재하는 가장 극명한 치외법권 장소로 보았다. 9•11 이후 미국이 테러와의 전쟁을 선포하면서 ‘적의 전투원’으로 의심되는 민간인들이 기소나 재판 절차 없이 관타나모에 수용되었다. 그 의심의 주체는 미국이었고, 국제 정치의 역학 관계 속에서 그 누구도 이들의 횡포에 문제를 제기하지 못했다. 테러는 비윤리적이며 응징받아 마땅하다는 당위 아래 미국이 호모사케르를 만들어 내는 과정은 묵인되고 심지어 정당화되었다.

미국은 잠재 테러범 혹은 테러 동조자로 의심되면 누구든지, 전 세계 어느 곳에서든지 잡아들여 관타나모에 가둬 버렸다. 관타나모는 감옥이 아니라 용의자를 위한 수용 시설이기에 전쟁 포로에 관한 제네바 협약의 적용을 받을 수도 없고, 쿠바령에 위치한다는 이유로 미국 내 인권보호법도 빗겨 나간다. 조사를 핑계로 구금은 무기한 연장되었고 법의 감시망을 피해 어떤 인권 남용도 방조되었다. 흡사 외계 행성인 듯 전혀 다른 세상처럼 작동한 것이다. 강제적인 튜브 영양을 통해 단식의 권한마저 박탈당한 관타나모의 수용자들은 죽을 권리조차 빼앗긴 생명이다.

이미지의 충돌

오바마 대통령은 취임과 동시에 관타나모 수용소의 폐쇄와 고문 중단을 명령했지만, 이곳은 여전히 건재하다. 관타나모 미 해군 기지는 그 지명을 축약한 GTMO 혹은 소리 나는 대로 GITMO라 부른다. 데비 콘월은 무려 9개월 동안 서류 작업과 신원 조회를 거쳐 GITMO 촬영에 성공했다. 그녀의 관타나모 작업 이전에 우리는 이미 이와 연관된 세 갈래의 이미지를 경험했다. 하나는 호모사케르를 가두고 감시하는 장소로서의 팬옵티콘(panopticon)이다. 18세기 말 영국의 공리주의자 제러미 벤담이 제안하고 이후 사회주의 국가 쿠바가 정치수용소로 직접 설계해 운영한 이 시설은 정중앙의 감시탑에서 감시자가 수용자를 한눈에 볼 수 있는 원형 감옥이다. 수용 시설의 효율적 운영을 위한 벤담의 애초 제안과 달리, 푸코는 수용자가 감시 상태를 내재화해 스스로 길들임을 당하는 상징적인 감시 기구로 파악했다.

이미지로서의 팬옵티콘은 신체가 가둬지고 감시받는 감옥의 원형(原型)이다. 감시탑을 중심에 두고 원 구조로 늘어선 똑같은 크기의 방들. 감시탑에서는 감옥 내부가 들여다보이나 감방에서는 감시탑을 들여다볼 수 없는 일방적인 시선의 차단. 비인간적으로 기계처럼 나열된 그 구조는 일사불란한 감시가 가능한 전형적인 수용 시설로 떠올랐다. 다만 이 공간이 작동하는 원리를 넘어 이 공간에서 벌어지는 사건은 공백으로 남겨져 있을 뿐이다.

대신 우리는 다른 이미지들을 통해 이 감시 체계 내부의 실상을 들여다본다. 그 하나는 테러와의 전쟁 직후 관타나모에 수용 시설이 갖춰지기 전, 철망으로 엮은 동물 사육장 같은 곳에 수용자들을 가둬 둔 장면이다. 또 다른 하나는 이라크 아브 그라이브 감옥에서 유출된 학대당하고 고문당하는 사진들이다. 관타나모 수용자들이 오렌지색 죄수복을 걸치고 얼굴이 봉지에 가려진 채 뜨거운 맨땅에 경직된 자세로 앉아 있는 모습은 팬옵티콘의 시스템 자체를 초월한다. 두 눈이 가려지고 귀마개까지 씌워진 용의자들은 자신이 어디에, 누구와 있는지 가늠할 수조차 없는 극단의 고립 상태다. 생물학적 인간으로서 생존을 위한 최소한의 감각 기관마저도 제거당한 셈이다.

설령 그들이 좀 더 개량된 시설로 옮겨져 수용된다 할지라도 더욱 끔찍한 학대와 고문이 기다릴 거라고 아브 그라이브의 사진들은 폭로한다. 더욱이 아브 그라이브의 잔혹한 이미지들이 내부자의 고발이나 사진기자의 밀착 취재에 의한 것이 아니라 어느 병사가 SNS에 장난으로 올린 거라는 점에서 사진의 역할과 운명은 꽤 복잡해진다. 병사들이 죄수를 학대하는 과정에서 촬영한 기념 사진은 수용자에게는 수치심을 동반한 끔찍한 시각적 고문이고, 병사에게는 그릇된 애국심이 불러일으킨 유희의 인증샷이며, 감옥 밖 목격자에게는 미국의 야만을 드러낸 증거였다. 아브 그라이브의 사진 이후 사진가들은 그보다 더 자극적인 사진을 만들어 낼 수 없었다. 그들은 기록의 주체이지 그런 상황을 생산하는 주체가 될 수 없기 때문이다. 또한 사진의 순기능이 존재한다면, 세상에서 이런 끔찍한 일들이 사라졌어야 하기 때문이다. 하지만 우리는 타인의 고통을 이해하려 한다는 명분 아래 더 자극적인 사진을 기대할지도 모른다.

투명 인간

데비 콘월의 관타나모 작업, <미군 부대에 오신 것을 환영합니다(Welcome to Camp America)>는 사진을 둘러싼 이 무기력하고 혼란스러운 질문의 연장선에 있다. 까다로운 절차와 통제, 엄격한 사후 검열을 통과한 사진에는 그 누구의 얼굴도 어떤 사건도 등장하지 않는다. 이미 목격한 수용소 사진들에 비한다면 한없이 냉정하고 정제되어 있다. 이 구도와 포즈는 미군의 검열을 전제로 한 작가의 전략적 판단이었을 것이다. 따라서 중립적이고 냉정해 보이는 데비 콘월의 이미지는 엄밀한 의미에서 정교하게 계산된 작가의 주관적 시선이기도 하다. 미군 당국마저 공개해도 된다고 판단한 데비 콘월의 사진들은 미국이 자국의 평화 유지를 명분 삼아 저지르는 폭력성과 위선을 더욱 선명하게 드러낸다. 야외 바비큐장과 수영장은 물론이고 18홀 골프 코스와 카트체험장까지 갖춘 관타나모는 미군과 그 가족에게는 100년 역사를 지닌 이국적인 카리브 해의 휴양지일 뿐이다. 심지어 데비 콘월을 안내한 병사는 ‘즐거움이 가득해 병사들이 배치를 원하는 최고의 부대’라는 말도 빠뜨리지 않았다. 그러나 어느 날 갑자기 끌려와 고문과 학대 속에 놓인 용의자에게는 끔찍한 지옥일 뿐이다. 수용자가 등장하지 않는 이장소는 너무 비현실적이어서 화려한 부대 모습 뒤 감춰진 현실의 더욱 모순적으로 보여 준다.

12년 넘게 출옥자를 위한 인권 변호사로 활동한 데비 콘월의 작업은 치밀한 자료 조사를 바탕으로 한다. 그녀는 관타나모 시설에 그치지 않고 풀려난 용의자들을 추적하여 기록하는 일도 계속하고 있다. 그녀가 조사한 내용을 보면 지난 15년 동안 780명의 용의자가 수감되었으나 단 8명만 유죄를 선고 받았다. 현재 관타나모에는 41명의 수용자가 남아있다. 그중 5명은 항소심에서 판결이 뒤집혔다. 무죄 판결을 받았는데도 혐의가 중대하다고 판단된 용의자들은 고향이 아닌 제3국으로 보내졌다. 이들은 자신의 의사와 상관없이 미국과 비밀 협정을 맺은 최소 35 개국 중 어딘가에서 가족과 헤어진 채 이방인으로 살아가는 중이다. 그들이 버려지다시피 정착한 땅의 언어를 모르는 것은 물론이다. 12년 동안의 수감 생활을 마치고 슬로바키아로 보내진 예멘 출신 후세인의 경우처럼.

그들은 지구상 어딘가에 존재하나 아무도 그들을 보았다고 말하지 않는 투명인간, 호모 사케르다. 데비 콘월의 작업은 미국은 어떤 나라인가가 아니라 현대 사회에서 국가란 그리고 생명이란 무엇인가를 묻는다.

글 | 송수정 기획자

For homo sacer

Planet Guantánamo

Homo sacer is a legal status defined by ancient Roman law. Despite its original definition of 'sacred man', a homo sacer could be killed anytime, and nobody would be punished for this murder. Even so, they were deemed unqualified as religious sacrifice as they were thought to be too filthy and distasteful to touch, cursed and despised, far from sacred. At the time, the lives of homo sacer were meaningless, their humanity denied by all. The term came to life again when Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben used it to explain brutality of modern nations.

While Foucault suggested that the mechanism of the modern nation enhancing power and discriminating among its people is justified by its desire to control child birth and disease, Agamben takes a step further and criticizes the modern nation for violently exploiting life itself for the sake of national interest. To Agamben, Guantánamo Bay in particular is the most evident 'extraterritorial' location for contemporary homo sacer. As the U.S.-claimed “War on Terror” after the 9.11 attack, civilians suspected of being “enemy combatants” were imprisoned in Guantánamo Bay without charge or trial. In the power game of international politics, America’s mere suspicion of these men silenced any opposing voices. The way America created homo sacer was tolerated and even justified by asserting that because terrorism is itself outside the law, it deserves be punished in kind.

Suspected terrorists around the world were arrested and brought to the U.S. Naval Station in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, or GTMO (pronounced “Gitmo”). Because, in the eyes of the U.S. government, Guantánamo is not a “prison” but a “detention center,” its inmates not “prisoners” but “enemy combatants” or “unprivileged belligerents,” Geneva Convention protections for prisoners of war do not apply. U.S. constitutional protections do not apply either because the military base stands on Cuban soil. The location was chosen explicitly to allow for indefinite detention and torturous interrogation, beyond the reach of the law. The place is like an extraterritorial planet, functioning as an entirely different world. The inmates at Guantánamo have no power except over their own bodies. Many have engaged in long-term hunger strikes to protest their indefinite detention. Yet they are stripped even of this right, reframed by the military as “long-term non-religious fasts,” as they are force-fed through a tube, a process referred to as “enteral feeding.”

Collision of images

President Obama ordered Guantánamo Bay to be shut down and called a halt to torture when he first came into office in 2009, but the institution still remains firm. The new President Trump may even enhance the facility. After 9 long months of paperwork and a background check, Debi Cornwall succeeded to capture the place.

Three related categories of images inform Cornwall’s work. The first is the panopticon, the location where homo sacer is imprisoned and monitored. The panopticon was designed by a late-18th century British utilitarian Jeremy Bentham, and was also adopted by socialist Cuba and applied to its political jails. This circular prison has a watchtower in the center, from where the guards can easily oversee the inmates. Unlike Benthem's initial design drafted for an effective management of the facility, Foucault interpreted this prison as a symbolic tool of surveillance where the prisoners inure themselves by internalizing their imprisonment status.

As an image, the panopticon is a prototype of prison where people are physically locked up and put under surveillance. Rooms of equal sizes are lined in circle around the watchtower. Unilateral and blocked vision allows prisoners to be seen from the tower but not the other way around. Prisoners must assume they are under constant surveillance. Efficient observation became possible at such an inhumane but mechanically arranged structure and it soon became a common jail design. Still, what lies beyond its functional mechanism and what is happening in that space remain as a void.

Instead, we look into the inner truth of this surveillance system through other images. The second category of images is scenes captured at Guantánamo Bay in 2002, when the first “War on Terror” inmates were kept in outdoor, cage-like cells in Camp X-Ray before the modern facilities were completed. Dressed in orange jumpsuits with their faces hooded, prisoners of Guantánamo sit rigidly on the scorching bare ground.

The images surpass the panopticon system itself. With their eyes blinded and ears shut with earplugs, the suspects are in extreme isolation without any idea as to where they are, with whom, or why. Not only are they stripped of their dignity as humans, but every single sensual organ necessary to survive as a biological being is removed from them.

The third category is pictures of abuse and torture that were leaked out of Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Even if they are relocated to a facility with better environment in Guantánamo Bay, the photos of Abu Ghraib disclose the fact that only more horrible abuse and torture are waiting for them there. The role and fate of photography become even more complicated considering that the cruel images of Abu Ghraib only came to light not by any whistleblower’s or photojournalist’s exposé, but by a joke posted on a soldier’s social media account. The souvenir photo taken while the soldiers were abusing the prisoners was a horrid visual torture accompanied by shame. To the soldiers the scene was a playful picture produced by misled patriotism and to the witnesses outside the camp it was an evidential photograph unveiling the barbaric side of America. Since the Abu Ghraib photos, no other photographer has been able to take a picture that is more intense, because a photographer is an agent of documentation and not the one who produces such conditions. If there is such a thing as positive effect of photography, such atrocious events should have been eradicated after those photos became public. Perhaps people may look forward to photographs showing even more, and excuse themselves for having such desire by telling themselves they are only trying to understand other people’s pain better.

Invisible men

Debi Cornwall’s Guantánamo Project, Welcome to Camp America, is in line with such helpless and confounding questions. Photographs limited by military regulations and meticulous daily inspections do not show any faces or events. Compared to the prison images that were witnessed in the past, Cornwall’s images are infinitely calm and refined. The compositions and the poses were most likely prearranged by the artist’s strategic decision as censorship by the U.S. military authorities was expected.

Therefore, to be more specific, Cornwall’s neutral and cold images are delicately calculated views of the artist herself.

Although the images were approved for release to the public even by U.S. military authorities, ironically enough they disclose the ideological violence and hypocrisy committed by the U.S. in the name of making its people feel safe. Guantánamo is equipped with outdoor barbecue facilities, swimming pools and even an 18-hole golf course and go-cart track, in keeping with its hundred-year history as an exotic Caribbean holiday destination for U.S. soldiers and their families. In the words of Debi Cornwall’s military escort, “Gitmo is the best posting a soldier can have. There’s so much fun here!” Yet to an inmate who was suddenly dragged into the place to be tortured and abused, it is only a dreadful hell on earth. Because the inmates are not featured in the images, they are quite surreal, revealing even more vividly the contradicting duplicity between the public show and the hidden reality.

A civil rights lawyer with more than 12 years of experience working with released prisoners across the U.S., Debi Cornwall’s work is based on detailed data analysis. She continues to document not only the Guantánamo facility itself but also former inmates who are cleared and released from the place. According to her study, 780 suspects were incarcerated over the last 15 years, and out of them only 8 were convicted in military commission proceedings—not criminal trials—of which 5 were overturned on appeal. Today, 41 men remain held.

Of those cleared and released, many did not return home, but, against their will and separated from their families, were instead transferred to live as aliens in one of at least 35 countries that have signed secret agreements with the U.S. Most do not even speak the language of the land they are abandoned in, like Hussein, a Yemeni transferred to Slovakia after 12 years in Guantánamo Bay. They are invisible men existing somewhere in the world but witnessed by nobody, modern homines sacri. It is not what kind of country the U.S. is that Debi Cornwall’s project questions. It questions what “country” is in a contemporary society.

Texts | Sujong Song Director

Debi Cornwall 데비 콘월

데비 콘월은 브라운대학교에서 현대문화와 미디어학과를 졸업한 후 사진가로 활동하다 하버드대학교 법학전문 대학원에서 박사학위를 취득했다. 이후 12년 동안 인권 변호사로 일했으며, 2014년부터 다큐멘터리 사진가로 다시 활동을 시작했다. 인권변호로사로서의 경험을 바탕으로 9·11 이후 미국의 국가 권력에 대해 집요한 물음을 던지고 있다. 《Welcome to Camp America》(제네바 사진센터, 2017), 《Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play, Gitmo on Sale》(갤러리 1401, 2016), 《Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play》(포베아 익시비션, 2015) 등의 다수의 개인전을 가졌고, 《엔콘트로스 다 이마젬 국제사진축제》(포르투갈, 2015), 《벨파스트 사진축제-Conceal & Reveal》(아일랜드, 2015), 《브라이튼 사진 비엔날레-나이트 컨택트》(영국, 2014) 등 여러 단체전에도 참여했다. 2016년 중국 리앤조사진축제 심사위원상인 푼크툼 어워드 등을 수상했으며, 현재 미국 뉴멕시코의 란난 재단, 휴스턴 미술관 등에서 작품을 소장하고 있다.

학력

2000 하버드대학교 법학전문대학원 법학박사

1995 브라운대학교 모던컬쳐&미디어학과 졸업

(EN)

2000 Harvard Law School, J.D., USA

1995 Brown University, Modern Culture&Media, B.A., USA

개인전

2017 《Welcome to Camp America》, 제네바 사진센터, 제네바, 스위스

2017 《리엔조 국제사진축제 푼크툼 어워드 특별전-Welcome to Came America》, 충칭, 중국

2016 《리엔조 국제사진축제-Welcome to Camp America》, 리엔조, 중국

2016 《Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play, Gitmo on Sale》, 갤러리 1401, 필라델피아, 미국

2015 《포토빌 사진축제-Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play》, 뉴욕, 미국

2015 《Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play》, Fovea Exhibitions, 뉴욕, 미국

(EN)

2017 Welcome to Camp America, Centre de la Photographie Genève, Switzerland

2017 Lianzhou Foto Touring Exhibition Punctum Award Special Exhibition-

2017 Welcome to Camp America, Chongqing, China

2016 Lianzhou Foto Festival-Welcome to Camp America, Lianzhou, China

2016 Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play, Gitmo on Sale, Gallery 1401, Philadelphia, USA

2015 Photoville-Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play, Gitmo on Sale, New York, USA

2016 Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play, Fovea Exhibitions, New York, USA

그룹전

2017 《Month of Photography Denver-Critical Mass TOP 50 Show》,

2017 아트워크네트워크 갤러리, 덴버, 미국

2016 《STUMP》, 칸델라 북스 + 갤러리, 버지니아, 미국

2015 《과테포토 국제사진축제》, 과테말라, 과테말라

2015 《엔콘트로스 다 이마젬 국제사진축제》, 브라가, 포르투갈

2015 《제21회 입선작 기획전 Peter Urban Legacy Edition》, 그리핀사진미술관, 매사추세츠, 미국

2015 《EXPOSURE 2015》, 포토그래픽 리소스센터, 매사추세츠, 미국

2015 《CAPTURED 2015》, 뉴스페이스 사진센터, 오리건, 미국

2015 《벨파스트 사진축제-Conceal & Reveal》, 벨파스트, 아일랜드

2015 《National Prize Show》, 카트린 슐츠 갤러리, 매사추세츠, 미국

2015 《제12회 알레포 국제사진축제》, 알레포, 시리아

2014 《레이던 국제사진축제-포토빌: 미국 젊은 사진가 20인》, 레이던, 네덜란드

2014 《브라이튼 포토 비엔날레-Night Contact》, 브라이튼, 영국

2014 《NEXT:》, 카스텔 갤러리, 노스 캐롤라이나, 미국

(EN)

2017 Critical Mass Top 50, Artwork Network, Denver, USA

2016 STUMP, Candela Books + Gallery, Virginia, USA

2015 GuatePhoto International Festival de Fotografía, Guatemala City, Guatemala

2015 Encontros da Imagem XXV International Photo Festival, Braga, Portugal

2015 21st Annual Juried Show, Peter Urban Legacy Exhibition,

2015 Griffin Museum of Photography, Massachusetts, USA

2015 EXPOSURE 2015, Photographic Resource Center, Massachusetts, USA

2015 CAPTURED 2015, Newspace Center for Photography, Oregan, USA

2015 Belfast Photo Festival-Conceal & Reveal, Belfast, Northern Ireland

2014 Leiden International Photo Festival-Photoville:

2014 20 Emerging American Photographers, Leiden, Netherlands

2014 Brighton Photo Biennial-Night Contact, Brighton, UK

2014 NEXT:, Castell Gallery, North Carolina, USA

수상

2016 리앤조 사진축제 푼크툼 어워드상, 중국

2015 인포커스 시드니 주버 사진상 선외가작, 오스트레일리아

2014 IPA 사진상 디퍼 퍼스펙티브 부문 선외가작, 미국

(EN)

2016 Punctum Award, Juried prize, Lianzhou Foto Festival, China

2015 INFOCUS Sidney Zuber Photography Award, Honorable Mention, Australia

2014 International Photography Awards,

20142014 Deeper Perspective Category-Honorable Mention, USA

Debi Cornwall 데비 콘월

Debi Cornwall is a conceptual documentary artist who returned to creative expression in 2014 after a 12-year career

as a civil rights lawyer.

Education

2000 Harvard Law School, J.D.

1995 Brown University, B.A., magna cum laude, Honors in Modern Culture & Media (photography)

1992-95 Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), photography classes

Monograph

Welcome to Camp America: Inside Guantánamo Bay (Radius Books 2017)

Solo Exhibitions

2017 Welcome to Camp America, Carriage House Gallery, Brown University (Providence, RI) (forthcoming 9 to 16 September)

2017 Welcome to Camp America, BMW Photo Space of GoEun Museum of Photography (S. Korea) (30 June to 26 August)

2017 Welcome to Camp America, Centre de la Photographie Genève (Switzerland)

2017 Punctum Award Special Exhibition, Lianzhou Foto Touring Exhibition, Chongqing (China)

2016 Welcome to Camp America, Lianzhou International Foto Festival (China)

2016 Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play, Gitmo on Sale, Gallery 1401, University of the Arts (Philadelphia, PA)

2015 Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play, Gitmo on Sale, Photoville (Brooklyn, NY)

2015 Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play, Fovea Exhibitions (Beacon, NY)

Selected Group Exhibitions

2017 Beirut Art Fair (Lebanon), Annalix Forever Genève Contemporary Art Gallery (forthcoming 21 to 24 September)

2017 Bending the Frame, Gulf + Western Gallery, NYU Tisch School of the Arts (NY, NY) (forthcoming August 25)

2017 Something Fierce, Lannan Foundation Gallery (Santa Fe, NM) (22 July to 17 September)

2017 Aperture Summer Open: On Freedom, Aperture Gallery, curated by For Freedoms (NY, NY) (13 July to 17 August)

2017 La Nuit de l’Année, les Rencontres d’Arles (France) (7 July)

2017 Critical Mass Top 50, Artwork Network (Denver, CO)

2016 STUMP, Candela Books + Gallery (Richmond, VA)

2015 Internacional Festival de Fotografía GuatePhoto (Guatemala)

2015 Encontros da Imagem International Photo Festival (Portugal)

2015 21st Annual Juried Show, Peter Urban Legacy Edition, Griffin Museum of Photography (Winchester, MA)

2015 EXPOSURE, Photographic Resource Center (Boston, MA)

2015 CAPTURED, Newspace Center for Photography (Portland, OR)

2015 Conceal & Reveal, Belfast Photo Festival (Northern Ireland)

2014 Photoville: 20 Emerging American Photographers, Leiden International Photo Festival (Netherlands)

1991 Student group show, Photographic Resource Center (Boston, MA)

Selected Collections

Lannan Foundation

Houston Museum of Fine Arts (promised gift, private collection)

Archive of Documentary Arts, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Selected Honors

2017-2019 Center for Emerging Visual Artists Fellowship

2017 Brown University Fitt Artist-in-Residence (forthcoming September)

2017 Arte Laguna Prize, Shortlist

2017 Magnum Foundation Fund Grant, Shortlist

2016 Punctum Award, Lianzhou Foto Festival (Juried prize)

2016 Baum Award for an Emerging American Photographer, Nominee

2016 Duke University Archive of Documentary Arts Collection Award for Women Documentarians

2016 Critical Mass Top 50

2016 Project and publication grants from the Vital Projects Fund at Proteus, Violet Jabara Charitable Trust,

David Rockefeller Fund, Elizabeth Firestone Graham Foundation, Puffin Foundation, and Pollination Project

2016 Gomma Photography Grant, Shortlist

2016 Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund Grant, Shortlist

2015 Speranza Foundation Lincoln City Fellowship

2015 NYFA Fiscal Sponsorship

2015 Critical Mass Finalist

2015 Felix Schoeller Photo Award (Germany), Shortlist (Conceptual and Editorial categories)

2015 Grand Prix International de Photographie de Vevey (Switzerland), Shortlist

2015 Phoenix Art Museum, INFOCUS Sidney Zuber Photography Award, Honorable Mention

2015 Athens Photo Festival, Shortlist

2014 Lensculture Narrative Storytelling Awards, Finalist (“Best 25 Visual Storytellers of 2014”)

2014 International Photography Awards, Honorable Mention (Deeper Perspective Category)

Selected Publications (Photo Essays)

In Print: Polka Magazine (France); Newsweek Japan; De Morgen (Belgium); International New York Times.

Online: Wired; British Journal of Photography; New York Times Magazine; New York Times Lens Blog.

Bibliography

Academic:

Daniel Grinberg, “Some Restrictions Apply: The Exhibition Spaces of Guantánamo Bay,” Cinema Journal (forthcoming 2018).

Esther Whitfield, Ph.D. “Guantánamo and Community: Visual Approaches to the Base,” in GUANTÁNAMO AND THE EMPIRE

OF FREEDOM, Don Walicek and Jessica Adams, eds. (Palgrave MacMillan) (forthcoming 2017).

Jean-Philippe Dedieu, “Guantánamo’s Frames of War: A Dialogue with Debi Cornwall and Larry Siems,” Humanity: An

International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, Vol. 8/1 (U. Penn. Press) (Spring 2017).

Selected Additional Reviews, Interviews, Project Profiles & News:

In Print:

Clémentine Mercier, “Coquillages et Cuirassés,” Exhibition review, Libération (France) (12 May 2017).

Samuel Schellenberg, “Bienvenu à Guantánamo,” Exhibition review, Le Courrier (Switzerland) (21 April 2017).

Monika Domann, “Welche Farben hat Orange?” Exhibition review, WOZ Die Wochenzeitung (Switzerland) (20 April 2017).

Caroline Stevan, “J'ai voulu montrer le fun de Guantánamo, selon les GIs,” Interview, Le Temps (Switzerland) (31 Mar. 2017).

Anna Aznaour, «J’ai photographié d’ex-détenus de Guantánamo,» Exhibition review, Tribune de Genève (22 March 2017)

Nata Zhu, Interview, Photoworld Magazine (China) (January 2017).

Marie Odile Perulli, “L’Oeil de Guantánamo,” Elle France (9 December 2016).

David Drake, “Fotofest 2016 Reviewer’s Choice,” Fotomagazin (Germany) (20 July 2016).

Elodie Cabrera, “Hors la Loi Américaine,” Polka Magazine (France) (October 2015).

Mark Feeney, “At the PRC, 13 Ways of Looking at the World,” Exhibition review, Boston Globe (25 June 2015).

Online & Radio:

Bruno Debreuil, “Debi Cornwall, Stratégies Photographiques Face au Contrôle de l’Information à Guantánamo,”

Exhibition review, Viens Voir, OAI13, (26 April 2017).

Nassim Daghighian, “Welcome to Camp America,” Exhibition & Book Review, Photo-Theoria 19 at pp. 1-6 (Spring 2017).

Florence Grivel, “Arts Visuels: Welcome Guantánamo,” Radio Interview (in French), Radio Espace 2 (16 March 2017).

Jörg Bader, “Debi Cornwall, Welcome to Camp America,” L’Oeil de la Photographie (15 March 2017).

Laura Malonee, "Female Photographers Matter Now More than Ever," Wired Magazine (6 February 2017).

Paige Goodpasture, "Stump: Photographers Use Their Lens to Make Us Look at Tough Issues," Exhibition review,

The Creative Habit, Soundcloud (1 September 2016).

Veronica Sanchis, “The Legacy of Guantánamo,” Photographic Museum of Humanity (18 May 2016).

Jeanette Moses, “12 Outstanding Documentary Photography Projects to See at Photoville 2015,” American Photo

Magazine (17 September 2015).

“The best of 2015’s Photoville – New York City's largest photo exhibition,” The Guardian (U.K.) (9 September 2015).

Mark Feeney, Review, “The Jury is In: Tokyo Interiors at Griffin Museum,” Exhibition review, Boston Globe (17 July 2015).

Elin Spring, Review, “Testify!” Exhibition review, What Will You Remember (blog) (24 June 2015).

Lindsay Comstock, “The 10 Best Photography Exhibits of Summer 2015,” American Photo Magazine (22 June 2015).

Pete Brook, “Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play,” Vantage (4 February 2015).

Ryan Wong, “Peeking into Guantanamo, Through a Detainee’s Art,” Hyperallergic (21 January 2015).

Pauline Eiferman, “Gitmo at Home, Gitmo at Play: Q&A with Debi Cornwall,” Roads & Kingdoms (23 October 2014).

Marco Werman, The World, Interview, Public Radio International (14 October 2014).

David Gonzalez, “Guantánamo’s Surreal Prison Landscape,” New York Times Lens Blog (14 October 2014).

Selected Artist’s Talks, Lectures, Panels & Teaching

Artist’s Lecture, BMW Photo Space of GoEun Museum (Busan, S. Korea) (30 June 2017).

Artist’s Lecture, School for Visual Arts (SVA), New York, NY (25 April 2017).

Presenter, Open Engagement (socially engaged artists’ conference), Chicago, IL (22 April 2017).

Panelist, Guantánamo, with investigative poet Frank Smith, moderated by curator Barbara Polla (in French),

Geneva, Switzerland (16 March 2017).

Panelist, “Saying War, Building Peace,” Palais des Nations, United Nations, Geneva, Switzerland (14 March 2017).

Artist's Lecture, Reiss-Engelhorn Museums, ZEPHYR raum für fotographie, Mannheim, Germany (24 May 2016).

Panelist, “Securing Support for Your Long-Term Projects,” Fotofest, Houston, TX (16 March 2016).

Photoville Education Day. Engaged NYC students in discussions about Guantánamo Bay, Brooklyn, NY (17 Sept. 2015).

Panelist, “Influencing Policy and Social Change through Photography,” Photoville, Brooklyn, NY (12 Sept. 2015).

Artist’s Lecture, Fovea Exhibitions, Beacon, NY (13 June 2015).

Artist’s Lecture, Doomed Gallery London, UK /Alternative Processes Collective (7 April 2015).

Panelist, “Art, Film and Guantánamo: a Special Freedom Flicks Event,” Brooklyn Public Library (14 January 2015).

Experience

2001-13 Neufeld Scheck & Brustin, LLP, Civil rights attorney (Partner 2006-13)

2000-01 Honorable Robert W. Sweet, U.S. District Court Judge (S.D.N.Y.), Law Clerk

1995-97 Federal Defender Division/Legal Aid Society (NYC), Investigator/Trial Assistant

1994-95 Associated Press, Providence, RI, Photographer (Stringer)

Representation

Steven Kasher Gallery

515 West 26th St., New York, NY 10001

info@stevenkasher.com